From permafrost microbes to survivor songbirds – research projects are also victims of COVID-19 pand

Three scientists describe the fieldwork they've had to delay in 2020 because of the pandemic. These are setbacks not just for their careers, but for the body of scientific knowledge.

What do you do when COVID-19 safety protocols and travel restrictions mean you can’t do your research? That’s what these three scientists have had to figure out this year, as the global pandemic has kept them from their fieldwork.

A microbiologist describes the frustration of missing a sampling season in the Arctic at a time when climate change means the permafrost is an endangered resource. A biologist writes about missing for the first time the annual census of a bird population she’s been studying for 35 years and the hole that leaves in her data. And natural events aren’t the only ones researchers are forced to skip. An environmental scientist explains how postponing a global gathering about climate change could have long-term effects for people like her who study the process – as well as for the planet.

Focus of this fieldwork is melting away

Karen Lloyd, microbiologist: In March 2020, COVID-19 travel restrictions caused my colleagues and me to abruptly cancel our fieldwork plans to sample permafrost in Svalbard, Norway. We have a narrow time window each year in which to do our work, since fully frozen ground, full snow cover and sunlight only cooccur reliably for a month or so in the spring.

Our project involves examining deep layers of permafrost. We want to know whether they’re likely to be sources or sinks for greenhouse gases such as carbon dioxide and methane as the permafrost thaws. We’ll use molecular biological techniques to examine how carbon moves through these precious ecosystems. This kind of knowledge will help us understand positive feedbacks between climate change and warming Arctic permafrost.

When we were forced to pull the plug on our fieldwork season, we had already shipped all our drilling equipment, our processing materials and even our personal gear to the U.K. Arctic Research Station in Ny Ålesund, Svalbard. So it’s all just been sitting there for nearly a year. Now we’re trying to make plans to do the work in spring 2021, but, given the COVID-19 forecast, it will likely be impossible again.

At 79 degrees north, this area has the some of the highest-latitude permafrost on the planet, and, like most permafrost, it is rapidly thawing. Temperatures in Svalbard were some of the highest on record this summer. No one has ever performed a detailed study of the microbial communities at this particular field site. And now that COVID-19 forces us to sit home instead of doing our work, some of this permafrost will thaw before anyone ever will.

2020 gap in a decadeslong record

Ellen Ketterson, biologist: Birds die every day. So do people. Learning why may help scientists understand what can and cannot be controlled about life spans.

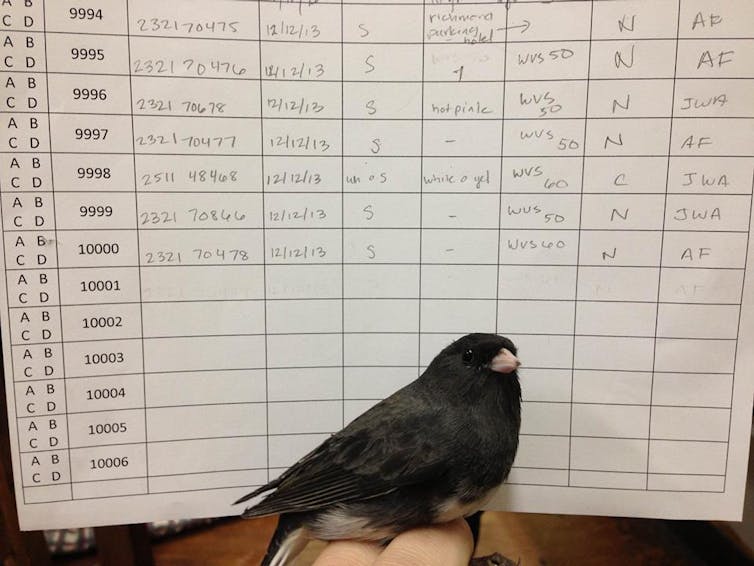

That’s why my research group and I have been following a population of marked songbirds known as dark-eyed juncos, or snowbirds, at Mountain Lake Biological Station in Virginia for more than 35 years. We track how many offspring the birds produce and how long they live by marking them with leg bands. We return each year to determine who is still alive and what attributes the survivors have.

Long-term field research can help answer some crucial questions. Males are more likely to be recaptured over time — are they healthier than females or just more sedentary? Is the likelihood of recapture constant over time? Do we see signs of aging – what we call senescence – in older birds? Or are there periods when the odds of surviving and reproducing are independent of age and more attributable to the luck of the draw, being born into good food years or into a glut of predators? Does breeding early or late in response to climate-induced earlier springs alter survival?

2020 is the first year since 1984 that we could not do our annual census. Because of the COVID-19 pandemic, we couldn’t travel and the biology station where we work was closed. We decided the need for caution exceeded the value of what we lost: a continuous record of individual bird lives and a chance to band each year’s offspring to follow in the future. We missed the continuity and the companionship of field research.

We can’t make up the gap, but we will resume in 2021, as long as the COVID-19 situation has improved. Ornithologists are committed to determining why North America has lost 3 billion birds in the past 50 years, and long term, seamless records of individual birds’ lives will help us learn the answer.

Gatherings canceled, momentum lost

Miriah Kelly, environmental scientist: When COVID-19 hit, it caused the delay and rescheduling of the annual meeting of the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC) Conference of the Parties (COP).

The COP serves as the one time each year when scientists, political leaders, policy negotiators and groups most affected by climate change, along with observers and the media, convene to negotiate the world’s most pressing and complex climate change issues. Back in March, the 26th Conference of the Parties was officially postponed from November 2020 to November 2021. The event will still be held in Glasgow, Scotland, assuming the pandemic is under control.

I attended my first COP as a graduate student in 2010, and it proved to be a transformative experience. Since then, I’ve focused my career on ocean and coastal climate change issues. Like many other academics who work in this space, I was planning to attend this year’s COP 26 to collect data and build collaborations with other researchers. Currently, I’m working on a 10-year analysis (2010-2020) of artifacts derived from the Conferences of the Parties to better understand how the narratives around ocean and coastal climate change have evolved over the past decade. Now it will be a nine-year assessment, with a caveat tacked on to the end.

The UNFCCC is still hosting a virtual Climate Dialogue this month. But delaying COP 26 is likely to have a great impact on the momentum of the UNFCCC. 2020 was supposed to be a time when countries would be submitting updated commitments to reduce national greenhouse gas emissions. The initial commitments were made in the Paris accord, a nonbinding treaty established in 2015 during COP 21, and were designed to incrementally increase over time.

Now that the COP is set back by a year, countries have been sluggish to move forward with the more ambitious commitments necessary to keep global temperatures from rising more than 2 degrees Celsius. Meanwhile, the most vulnerable communities of the least-developed countries are already suffering the impacts of rising temperatures and seas.

Though virtual events and long-distance collaboration are the best alternatives to in-person meetings at this point, organic interpersonal communication is hindered, and broad participation from diverse stakeholder groups is stifled.

The vast implications of the pandemic for climate change are unknown. But it’s clear that time is running out to substantively address this issue at the global scale, and these COP events have been pivotal to whatever progress has been made.

[Get our best science, health and technology stories. Sign up for The Conversation’s science newsletter.]

Karen Lloyd receives funding from the U.S. Department of Energy, Office of Science, Office of Biological and Environmental Research, Genomic Science Program under Award Number DE-SC0020369.

Ellen Ketterson has received funding from the National Science Foundation and Indiana University Grand Challenge, Prepared for Environmental Change.

Miriah Kelly receives funding from US Department of Housing and Urban Development (via University of Connecticut CIRCA) for research related to the Resilient Connecticut project. She has received funding in the past from National Oceanic and Atmospheric Association via the Sea Grant programs in Oregon and Connecticut.

Read These Next

Billions of dollars, decades of progress spent eliminating devastating diseases may be lost with und

Public health campaigns had made significant strides toward eradicating diseases like elephantitis and…

Operational secrecy kept the US from making evacuation plans – and that means Americans in the Midea

A longtime diplomat explains how the State Department normally encourages and helps Americans to leave…

2025 was hotter than it should have been – 5 influences and a dirty surprise offer clues to what’s a

Solar cycles, sea ice and rising electricity use all play a role. So does an unhealthy surprise that…