What every new baker should know about the yeast all around us

Yeast is a single-celled organism that's everywhere around us. Understanding how yeast works can help you make better bread and appreciate this old friend of humanity.

With people confined to their homes, there is more interest in home-baked bread than ever before. And that means a lot of people are making friends with yeast for the first time. I am a professor of hospitality management and a former chef, and I teach in my university’s fermentation science program. As friends and colleagues struggle for success in using yeast in their baking – and occasionally brewing – I’m getting bombarded with questions about this interesting little microorganism.

A little cell with a lot of power

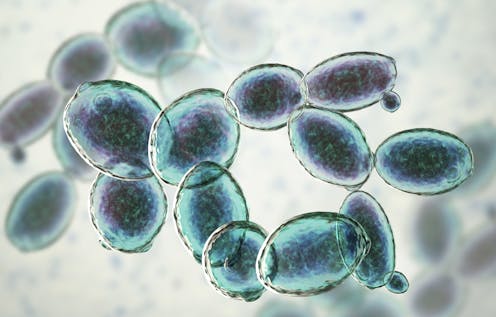

Yeasts are single-celled organisms in the fungus family. There are more than 1,500 species of them on Earth. While each individual yeast is only one cell, they are surprisingly complex and contain a nucleus, DNA and many other cellular parts found in more complicated organisms.

Yeasts break down complex molecules into simpler molecules to produce the energy they live on. They can be found on most plants, floating around in the air and in soils across the globe. There are 250 or so of these yeast species that can convert sugar into carbon dioxide and alcohol – valuable skills that humans have used for millennia. Twenty-four of these make foods that actually taste good.

Among these 24 species is one called Saccharomyces cerevisiae, which means “sugar-eating fungus.” This is bread yeast, the yeast we humans know and love most dearly for the food and drinks it helps us make.

The process starts out the same whether you are making bread or beer. Enzymes in the yeast convert sugar into alcohol and carbon dioxide. With bread, a baker wants to capture the carbon dioxide to leaven the bread and make it rise. With beer, a brewer wants to capture the alcohol.

Bread has been “the staff of life” for thousands of years. The first loaf of bread was probably a happy accident that occurred when some yeast living on grains began to ferment while some dough for flatbreads – think matzo or crackers – was being made. The first purposely made leavened bread was likely made by Egyptians about 3,000 years ago. Leavened bread is now a staple in almost every culture on Earth. Bread is inexpensive, nutritious, delicious, portable and easy to share. Anywhere wheat, rye or barley could be grown in sufficient quantities, bread became the basic food in most people’s diet.

No yeast, no bread

When you mix yeast with a bit of water and flour, the yeast begins to eat the long chains of carbohydrates found in the flour called starches. This does two important things for baking: It changes the chemical structure of the carbohydrates, and it makes bread rise.

When yeast breaks down starch, it produces carbon dioxide gas and ethyl alcohol. This CO2 is trapped in the dough by stringy protein strands called gluten and causes the dough to rise. After baking, those little air pockets are locked into place and result in airy, fluffy bread.

But soft bread is not the only result. When yeast break down the starches in flour, it turns them into flavorful sugars. The longer you let the dough rise, the stronger these good flavors will be, and some of the most popular bread recipes use this to their advantage.

The supermarket’s out of yeast; now what?

Baking bread at home is fun and easy, but what if your store doesn’t have any yeast? Then it’s sourdough to the rescue!

Yeast is everywhere, and it’s really easy to collect yeast at home that you can use for baking. These wild yeast collections tend to gather yeasts as well as bacteria – usually Lactobacillus brevis that is used in cheese and yogurt production – that add the complex sour flavors of sourdough. Sourdough starters have been made from fruits, vegetables or even dead wasps. Pliny the Elder, the Roman naturalist and philosopher, was the first to suggest the dead wasp recipe, and it works because wasps get coated in yeasts as they eat fruit. But please don’t do this at home! You don’t need a wasp or a murder hornet to make bread. All you really need to make sourdough starter is wheat or rye flour and water; the yeast and bacteria floating around your home will do the rest.

To make your own sourdough starter, mix a half-cup of distilled water with a half-cup of whole wheat flour or rye flour. Cover the top of your jar or bowl loosely with a cloth, and let it sit somewhere warm for 24 hours. After 24 hours, stir in another quarter-cup of distilled water and a half-cup of all-purpose flour. Let it sit another 24 hours. Throw out about half of your doughy mass and stir in another quarter-cup of water and another half-cup of all-purpose flour.

Keep doing this every day until your mixture begins to bubble and smells like rising bread dough. Once you have your starter going, you can use it to make bread, pancakes, even pizza crust, and you will never have to buy yeast again.

More than just bread and booze

Because of their similarity to complicated organisms, large size and ease of use, yeasts have been central to scientific progress for hundreds of years. Study of yeasts played a huge role in kick-starting the field of microbiology in the early 1800s. More than 150 years later, one species of yeast was the first organism with a nucleus to have its entire genome sequenced. Today, scientists use yeast in drug discovery and as tools to study cell growth in mammals and are exploring ways to use yeast to make biofuel from waste products like cornstalks.

Yeast is a remarkable little creature. It has provided delicious food and beverages for millennia, and to this day is a huge part of human life around the world. So the next time you have a glass of beer, toast our little friends that make these foods part of our enjoyment of life.

[Insight, in your inbox each day. You can get it with The Conversation’s email newsletter.]

Jeffrey Miller does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organisation that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

Read These Next

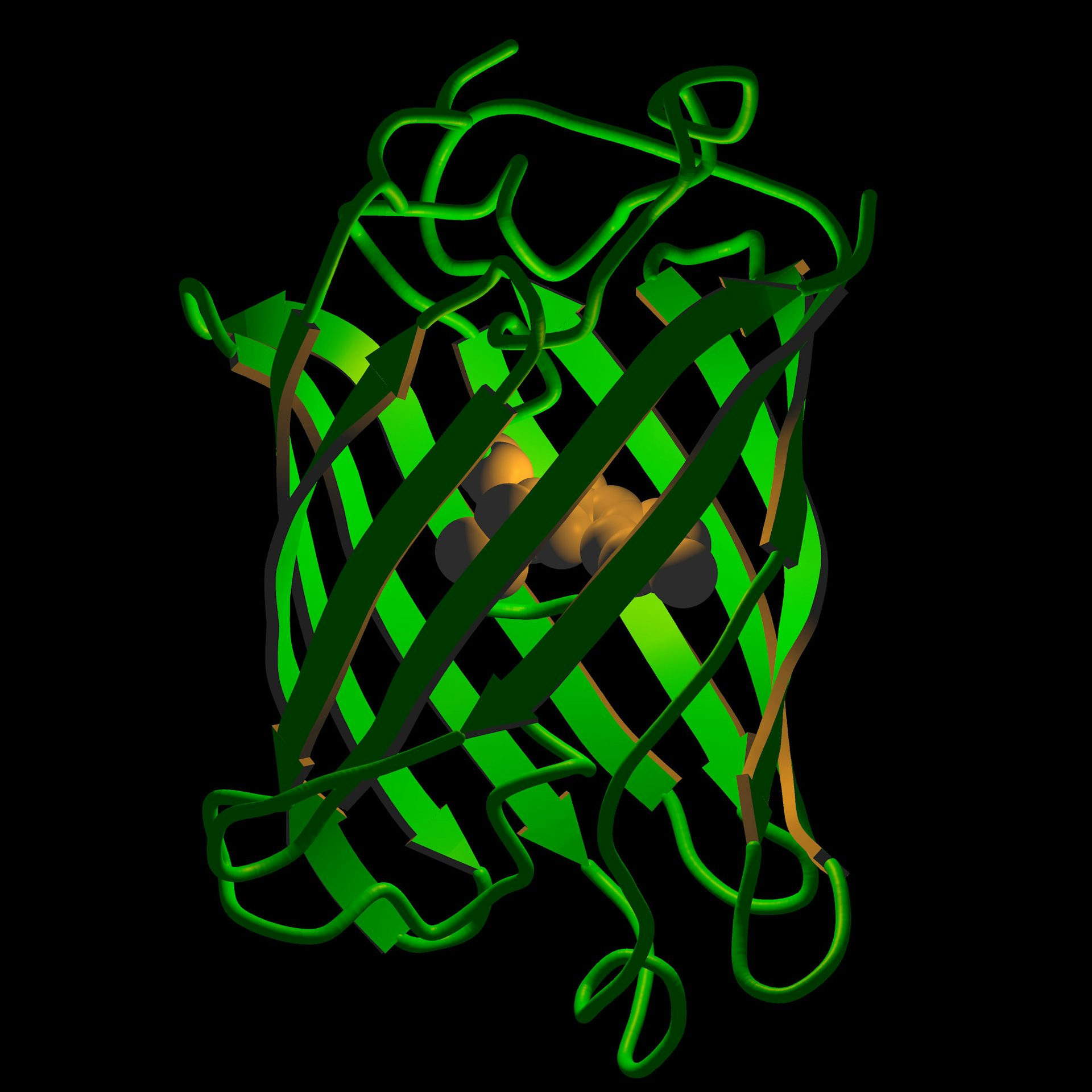

1 protein to rule them all – why crowning the protein that makes jellyfish glow green as a model can

Researchers have been studying tens of thousands of proteins and even more variations without a yardstick…

Colleges face a choice: Try to shape AI’s impact on learning, or be redefined by it

Colleges and universities are taking on different approaches to how their students are using AI –…

The Supreme Court may soon diminish Black political power, undoing generations of gains

The Supreme Court appears poised to abolish a key part of the Voting Rights Act. It may draw on a constitutional…