Social distancing increased over the course of human history – but so did empathy and new ways to co

People have changed over time, growing ever more distant and isolated from others – while at the same time finding new ways and technologies that let individuals connect and feel with others.

Social distancing is vital in the present moment. While the increased isolation and spacing of the new drastic measures come as shock to many people, social distancing is not new if you take the long view – the very long view.

As a cognitive scientist and scholar who studies empathy, I see human history as a process of increasing social distancing. Along the way, empathy emerged to bridge the widening gaps, allowing physical distance while encouraging mental bonds. In fact, I suggest that cultural practices of empathy changed over time, from mere tracking of others to “co-experiencing the situations of others” from a distance.

Staying connected over wider spaces

Our ancient African ancestors lived in groups of perhaps 150 individuals. According to evolutionary psychologist Robin Dunbar, human beings could live in these larger groups because they developed new forms of social interaction their predecessors didn’t have.

Our human ancestors replaced the physical grooming that bonded other apes with gossiping. By means of social chitchat, these first humans could focus attention on the members of their group. Physical distance could grow, while group members stayed close in a new mental way by tracking each other through spoken language. Grooming became obsolete.

Somewhere in our species’ transition from a fully nomadic existence to more permanent dwellings, separations emerged. Caves and walls unite smaller groups, but separate them from others. While researchers don’t know much about this time period, they have discovered stunning cave paintings dating back many thousands of years that depict hunting scenes. It’s impossible to say whether these images represent memories of past hunts or mythological scenes, but they illustrate how imagination transcends the walls.

Fast forward to the early modern age: Living communities became smaller and the nuclear family of mother-father-child became the new norm. This family structure started to exclude further removed relatives and members of the household. In the age of the nuclear family, social distance grew tremendously. Not just separation, but privacy became a key value. Around 1800, the Romantics celebrated being in a very small group and being alone.

Again, a new technique of empathy emerged that made the new social distance palatable: the novel. Novels provided people with a way to experience what others felt from a far off distance. Empathy now became detached from proximity of time and space, and in fact, reality. You can sit alone in your room and feel with and for others.

Empathy could become universal and apply to everyone, including in far away places. As the historian Lynn Hunt has argued, the idea of human rights was born and emerged parallel to the sentimental novel.

How empathy isolates the self

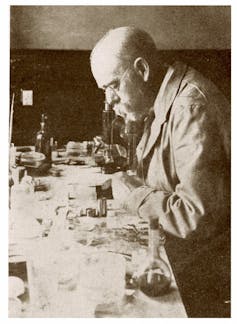

In 1882, the microbiologist Robert Koch identified the bacteria that cause and transmit tuberculosis. His discovery changed how people view each other – the possibility of passing germs makes contact with others a risk.

Consequently, the international hygiene movement emerged around the turn of the 20th century. The winning strategy to cope with the risk of contact, then and now, is self-control: tactics like cleaning regimes and self-isolation. In the relation of self and other, the self became dominant in Western culture.

Something interesting happened at the same time: Empathy also became more about the self than the other. In fact, it was around this time that the very word “empathy” was coined. It was born to translate the concept of “Einfühlung” from German art theory, which literally means feeling yourself into an artwork. In this concept, the individual who practices empathy faces an artifact, not another human being.

Since 2000, social media have cultivated a new mixture of social distance and empathy. While researchers have not generally agreed whether social media decrease or increase social bonds, time spent on social media is time spent without physical proximity to other people.

These technologies have transformed one’s small cliques of friends to an amorphous collection of followers at a distance. These networks increase social distance by satisfying the need for social connection. Likes and retweets provide the pleasant feeling of mattering to others. Having resonance on the internet thus enables physical social distancing and perhaps mental social distancing, too.

Social distancing in 2020

The human trajectory of increasing social distance paired with new forms of empathy and related techniques, ranging from novel-reading to social media, might suggest that people are set to weather the current socially distanced situation.

And yet, there’s another side to what is happening now. While over the millennia, human beings have adapted to various forms of distancing, we have not lost the appeals of being close. Most people crave the presence of people, real physical beings with bodies and emotions.

As a species and individually, people indeed can adapt to social distance. But I suggest that once in a while we want to leave all of these adaptations behind and just meet people and rub shoulders. We may even rediscover some form of grooming.

[Get facts about coronavirus and the latest research. Sign up for The Conversation’s newsletter.]

Fritz Breithaupt does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organization that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

Read These Next

AI’s growing appetite for power is putting Pennsylvania’s aging electricity grid to the test

As AI data centers are added to Pennsylvania’s existing infrastructure, they bring the promise of…

Why US third parties perform best in the Northeast

Many Americans are unhappy with the two major parties but seldom support alternatives. New England is…

Abortion laws show that public policy doesn’t always line up with public opinion

Polls indicate majority support for abortion rights in most states, but laws differ greatly between…