DNA testing companies offer telomere testing – but what does it tell you about aging and disease ris

Genetic testing companies are offering tests that analyze the ends of your chromosomes – telomeres – to gauge your health and your real age. But is there scientific evidence to support such tests?

Over the past few years direct-to-consumer genetic tests that extract information from DNA in your chromosomes have become popular. Through a simple cheek swab, saliva collection or finger prick, companies offer the possibility of learning more about your family tree, ancestry, or risk of developing diseases such as Alzheimer’s or even certain cancers. More recently, some companies offer tests to measure the tips of chromosomes called telomeres to learn more about aging.

But what exactly are telomeres, what are telomere tests, and what are companies claiming they can tell you? Age based on your birthday versus your “telomere age”?

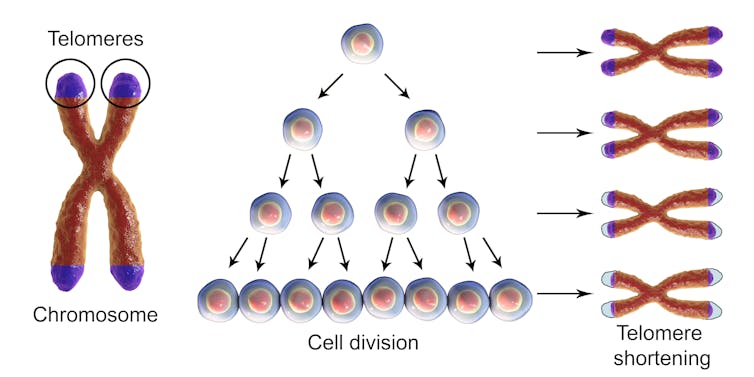

Telomeres play a big role in keeping our chromosomes and bodies healthy even though they make up only a tiny fraction of our total DNA. The Greek origins of the word telomere describes where to find them. “Telo” means “end” while “mere” means “part.” Telomeres cap both ends of all 46 chromosomes in each cell, and protect chromosomes from losing genetic material. They are often compared to the plastic tips at the ends of shoelaces that prevent fraying.

We are molecular biologists studying how chemicals, agents from the environment and metabolism damage telomeres and affect their lengths and function, and how damaged telomeres affect the health of our cells and genome. The idea of offering telomere length as part of a genetic test is intriguing since telomeres protect our genetic material. But equating telomere length with something as complex as aging struck us as tricky and overly simplistic.

Link between telomere length and human diseases

Telomeres are important for human health and despite their protective function, they are not indestructible. Telomeres shorten every time a cell divides and shorten progressively as we age.

When telomeres become too short or lost, the chromosome tips are left unprotected and become sticky. This can cause chromosomes to fuse. To prevent further chromosome shortening and fusions, the cells enter senescence, a state in which they can no longer divide. Although they lose the ability to rejuvenate tissues, senescent cells can still promote inflammation and secrete factors that favor growth of nearby pre-cancerous or cancerous cells.

Unfortunately, our lifestyle can actually accelerate the shortening. Environmental exposures such as sunlight, air pollution, cigarette smoke and even inflammation or poor diet can damage cell components, including DNA. They do this by generating unstable oxygen molecules, or free radicals. Telomeres are particularly susceptible to damage by free radicals.

Chemist Marcel Bruchez and I have developed a new tool that damages just the telomeres and only the telomeres. Using this tool we discovered that oxidative damage to telomeres is sufficient to not only accelerate their shortening but also to cause telomere loss.

In previous laboratory experiments, scientists found that eliminating senescent cells from mice led to the delay or prevention of diseases and conditions associated with aging including heart disease, diabetes, osteoporosis and lung fibrosis. This has led to the pursuit of new drugs called senolytics that could eliminate senescent cells in humans.

Is longer better?

Since short telomeres cause cells to senesce, this makes them interesting targets for healthy, disease-free aging. Also, since telomeres shorten with age, regardless of exposure to toxins this led to the notion that telomere length may provide information about a person’s “true” biological age.

Commercial tests typically measure telomere lengths or amounts of telomeric DNA in a blood sample. Companies compare your telomeres to telomeres from people of similar age to try to determine the biological age of your blood cells.

However, just as individuals of the same age vary in height and weight, so do telomeres. If a child falls in the 40th percentile for height, this means compared to 100 girls her age she is taller than 40. For this reason, charts similar to growth charts for children have been generated for telomeres.

Individuals with telomere lengths below the first percentile are at risk for developing specific diseases including anemia, immunodeficiency and pulmonary fibrosis, likely due to a gene mutation that impairs telomere maintenance

At the other extreme, individuals with gene mutations that lead to very long telomeres above the 99th percentile are at greater risk for developing inherited forms of melanoma and brain cancers. Longer telomeres allow a cell to divide more times, and with every division there is a chance that an error during genome duplication produces a mutation that promotes cancer. In a way, telomeres follow the Goldilock’ principle. Telomeres that are too short or too long are not optimal.

Can telomere length predict health outcomes?

But what about telomere lengths in between the extremes? Large studies involving hundreds to thousands of participants show general associations of shorter telomeres with increased risk for some diseases of aging, including heart disease, whereas longer telomeres are associated with increased risk for some types of cancers.

But translating these population studies to predictions about individual life spans and health is difficult. For example, as a group, men are taller than women, but that does not mean all men are taller than women. Similarly, some people with shorter telomeres do not develop heart disease in these population studies. More studies are needed to fully understand what an individual’s telomere length means for their health and aging.

While large population studies show a healthy diet is associated with longer telomeres, published reports about specific supplements that claim to support telomere health are lacking.

If such a product could extend telomeres, would it be safe? Or would it increase one’s risk for developing cancer due to long telomeres? Can protecting telomeres or slowing their shortening promote disease-free aging? We do not have the answers to these questions yet.

Given the uncertainty and risk of wrong interpretation, should you have your telomeres measured? Maybe, if the results motivate healthy lifestyle changes. For now, a surer bet for healthy aging would be to spend the money on exercise programs and nutritious foods instead.

Patricia Opresko receives funding from the National Institutes of Health.

Elise Fouquerel receives funding from National Institutes of Health.

Read These Next

Last nuclear weapons limits expired – pushing world toward new arms race

The expiration of the New START treaty has the US and Russia poised to increase the number of their…

The greatest risk of AI in higher education isn’t cheating – it’s the erosion of learning itself

Automating knowledge production and teaching weakens the ecosystem of students and scholars that sustains…

‘Learning to be humble meant taming my need to stand out from the group’ – a humility scholar explai

Humility is a virtue that many people admire but far fewer practice. A scholar describes how a professional…