Angkor Wat archaeological digs yield new clues to its civilization's decline

Many tourists hold an outdated romanticized image of an abandoned temple emerging from the jungle. But research around Angkor Wat suggests its collapse might be better described as a transformation.

Cambodia’s famous temple of Angkor Wat is one of the world’s largest religious monuments, visited by over 2 million tourists each year.

It was built in the early 12th century by King Suryavarman II, one of the most famous kings of the Angkorian civilization that lasted from approximately the ninth to 15th centuries. The structure is so strongly associated with Cambodian identity even today that it appears on the nation’s flag.

For many years, historians placed the collapse of the Angkor civilization in 1431, when Angkor’s capital city was sacked by the Thai Kingdom of Ayutthaya and abandoned. The idea that the Angkorian capital was abandoned also played a part in the 19th-century colonial interpretation of Angkor as a civilization forgotten by the Cambodians and left to decay in the jungle. Many tourists still come to Angkor Wat with an outdated romanticized notion of a deserted ruin emerging from the mysterious jungle.

But scholars have long argued against this interpretation, and archaeological evidence is shedding even more light on the decline of the Angkorian civilization. The process was much longer and more complex than previously imagined; Angkor’s collapse may be better described as a transformation.

By looking at the events associated with this one particular temple, archaeologists like me are able to see a microcosm of some of the broader regional transformations that took place across Angkor.

What happened to the Angkor civilization?

Researchers believe the Angkor civilization was established in A.D. 802. Its heartland and capital city was on the banks of the Tonle Sap Lake in northwest Cambodia. The Angkorian state was founded and grew during a period of favorable climate with abundant rainfall. At its height, Angkorian rulers might have controlled a large portion of mainland Southeast Asia.

The Angkor civilization was booming in the early 1100s when construction began on the Angkor Wat temple site. Built as a re-creation of the Hindu universe, its most striking features are the five sandstone towers that rise above the four temple enclosures, representing the peaks of Mount Meru, the center of the universe. The temple is surrounded by a large moat symbolizing the Sea of Milk from which “amrita,” an elixir of immortality, was created.

But by the end of the 13th century, numerous changes were taking place. The last major stone temple at Angkor was constructed in 1295, and the latest Sanskrit inscription dates to the same year. The last inscription in Khmer, the language of Cambodia, appears a few decades later in 1327. Constructing stone temples and writing inscriptions are elite activities – these last instances at the Angkorian capital happened during the region-wide adoption of Theravada Buddhism that replaced Hinduism.

This religious shift disrupted the pre-existing Hindu-based power structures. Emphasis moved from state-sponsored stone temples and royal bureaucracy to community-based Buddhist pagodas, built from wood. At the same time, maritime trade with China was increasing. The relocation of the capital further south, near the modern capital of Phnom Penh, allowed rulers to take advantage of these economic opportunities.

Paleoclimate research has highlighted region-wide environmental changes that were taking place at the time, too. A series of decades-long droughts, interspersed with heavy monsoons, disrupted Angkor’s water management network meant to capture and disburse water.

One study of the moats around the walled urban precinct of Angkor Thom suggest the city’s elite were already departing by 14th century, almost 100 years before the supposed sack of the capital by Ayutthaya.

Excavations in the Angkor Wat temple enclosure

My colleagues and I, in collaboration with the government’s APSARA Authority that oversees Angkor Archaeological Park, began excavating within Angkor Wat’s temple enclosure in 2010.

Instead of focusing on the temple itself, we looked at the occupation mounds surrounding the temple. In the past, people would have constructed houses and lived on top of these mounds. LiDAR surveys in the region clarified that Angkor Wat, and many other temples including nearby Ta Prohm, were surrounded by a grid-system of mounds within their enclosures.

Over three field seasons, my colleagues and I excavated these mounds, uncovering remains of dumps of ceramics, hearths and burnt food remains, post holes and flat-lying stones that might have been part of a floor surface or path.

It is not clear yet who lived on these mounds, as we have not yet found artifacts that give clues as to the inhabitants’ occupations. Inscriptions describe the thousands of people needed to keep the temples functioning, so we suspect that many of those who lived on the mounds worked in some capacity in the Angkor Wat temple, perhaps as religious specialists, temple dancers, musicians or other laborers.

During our excavations, we collected burnt organic remains, primarily pieces of wood charcoal that were associated with different layers or features like hearths. Using radiocarbon dating, we identified dates for 16 charcoal pieces. We used these dates to build a more fine-grained chronology of when people were using the temple enclosure space – providing a more nuanced idea of the timing of occupation at Angkor Wat.

Radiocarbon dates tell a different story

Our dates show that the landscape around Angkor Wat might have initially been inhabited in the 11th century, prior to the temple’s construction in the early 12th century. Then the Angkor Wat temple enclosure’s landscape, including the mound-pond grid system, was laid out. People subsequently inhabited the mounds.

Then we have a gap, or break, in our radiocarbon dates. It’s difficult to line it up with calendar years, but we think it likely ranges from the late 12th or early 13th century to the late 14th or early 15th century. This gap coincides with many of the changes taking place across Angkor. Based on our excavations, it seems that the occupation mounds were abandoned or their use was transformed during this period.

However, the temple of Angkor Wat itself was never abandoned. And the landscape surrounding the temple appears to be reoccupied by the late 14th or early 15th centuries, during the period Angkor was supposedly sacked and abandoned by Ayutthaya, and used until the 17th or 18th centuries.

Angkor Wat as a microcosm of the civilization

As one of the most important Angkorian temples, Angkor Wat can be seen as a kind of bellwether for broader developments of the civilization.

It seems to have undergone transformations at the same time that the broader Angkorian society was also reorganizing. Significantly, though, Angkor Wat was never abandoned. What can be abandoned is the tired cliche of foreign explorers “discovering” lost cities in the jungle.

While it seems clear that the city experienced a demographic shift, certain key parts of the landscape were not deserted. People returned to Angkor Wat and its surrounding enclosure during the period that historical chronicles say the city was being attacked and abandoned.

To describe Angkor’s decline as a collapse is a misnomer. Ongoing archaeological studies are showing that the Angkorian people were reorganizing and adapting to a variety of turbulent, changing conditions.

[Like what you’ve read? Want more? Sign up for The Conversation’s daily newsletter.]

Alison Kyra Carter receives funding from the Earthwatch Institute. Fieldwork described in this article was also supported by the National Geographic Society Committee for Research and Exploration Grant Number #9602-14, the Australian Research Council under grant DP1092663, and the Dumbarton Oaks Project Grant in Garden and Landscape Studies.

Read These Next

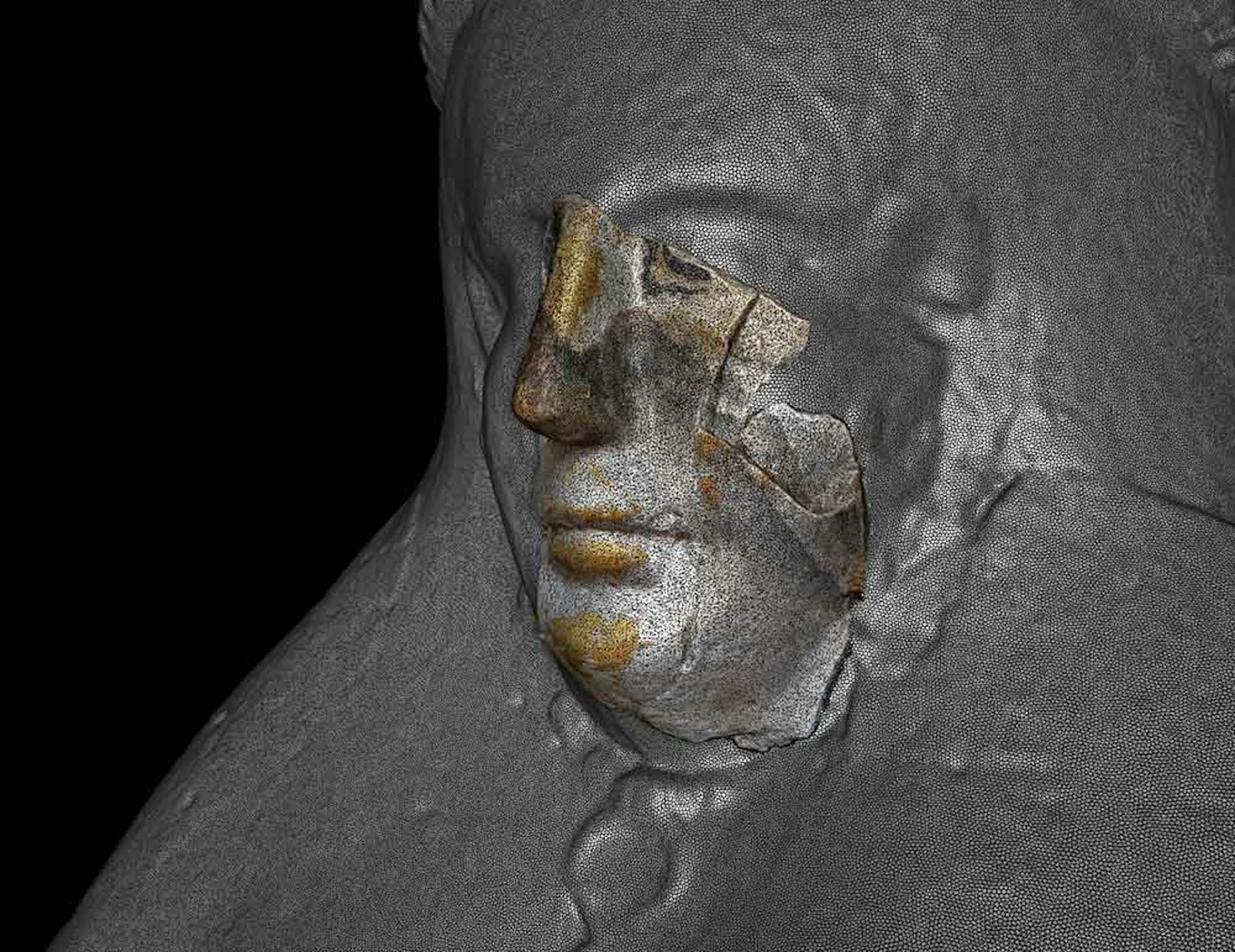

3D scanning and shape analysis help archaeologists connect objects across space and time to recover

Digital tools allow archaeologists to identify similarities between fragments and artifacts and potentially…

As Jeff Bezos dismantles The Washington Post, 5 regional papers chart a course for survival

Other billionaires who own newspapers are doing a better job, a journalism professor explains.

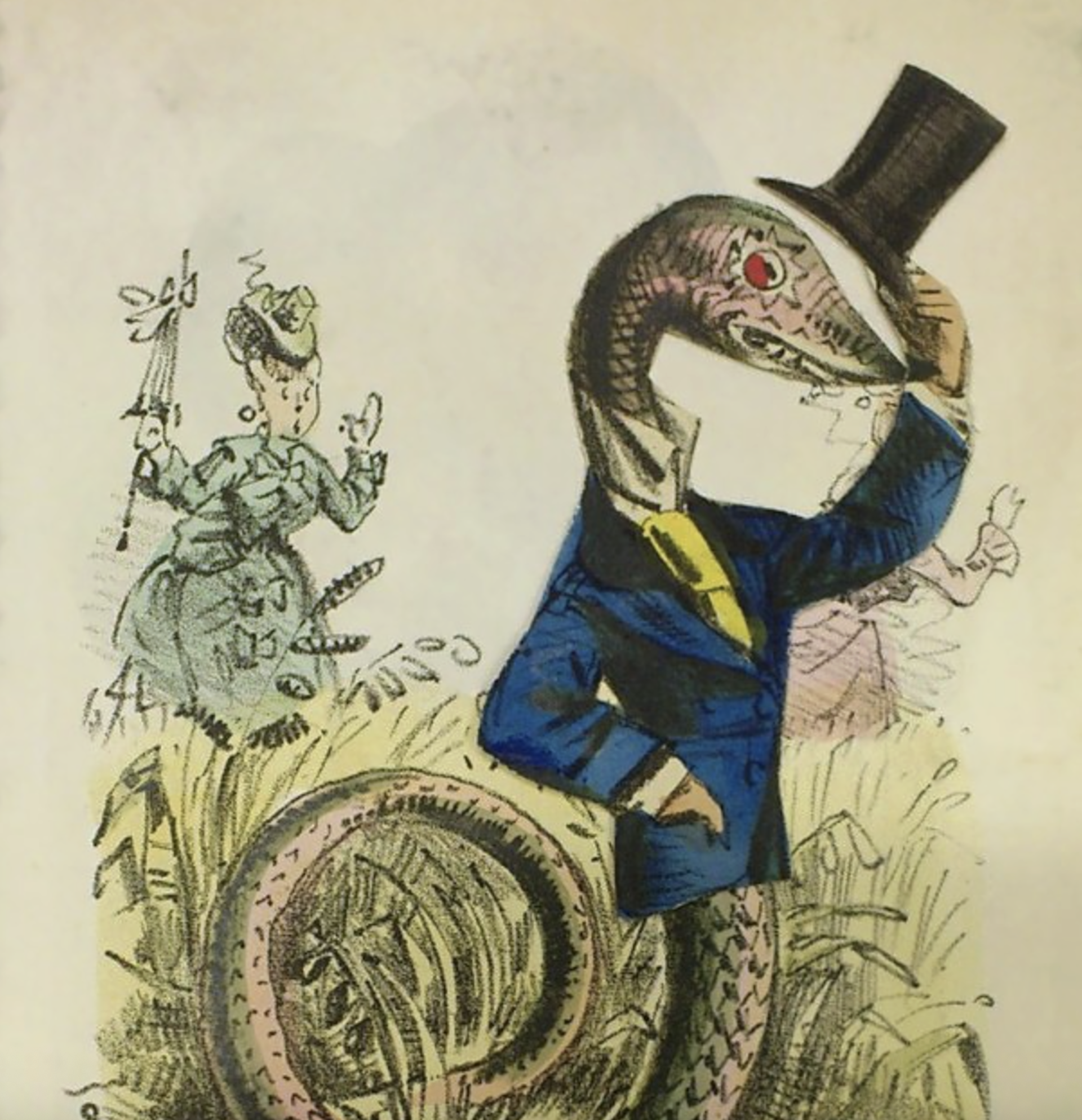

Valentine’s Day cards too sugary sweet for you? Return to the 19th-century custom of the spicy ‘vine

Victorians found a way to anonymously tell people they didn’t like exactly how they felt.