Russia isn't the first country to protest Western control over global telecommunications

Vladimir Putin's complaints about Western power over telecommunications echo – if not co-opt – concerns raised by less powerful nations for decades.

As the international community becomes increasingly concerned about misinformation and data breaches, the Russian government has announced plans to test its own, sweeping solution to the problem: disconnecting Russia from the global internet.

Russian President Vladimir Putin has argued that internet administration is too concentrated in the U.S., and that online misinformation campaigns threaten Russia’s national security. Reaction from the international press and tech experts has ranged from horrified to bemused, calling Russia’s behavior an act of totalitarian censorship or economic and technological recklessness.

But neither these problems nor Putin’s intended solution are particularly new. In fact, my research on the history of international telecommunications and information policy suggests that these criticisms echo – if not co-opt – a set of arguments and policy proposals based in other, less powerful nations’ historically reasonable objections about the West’s (especially the United States’) disproportionate power over international communications.

When developing states demanded global telecommunications reform after World War II, the U.S. began to evade and undermine efforts by intergovernmental organizations to manage information flows between countries. This U.S. policy, as it has unfolded over the last six decades, has played a major role in establishing the world’s current international communications system, centered on an internet that is less regulated than any of the technologies that preceded it and made it possible.

The origins of the international network

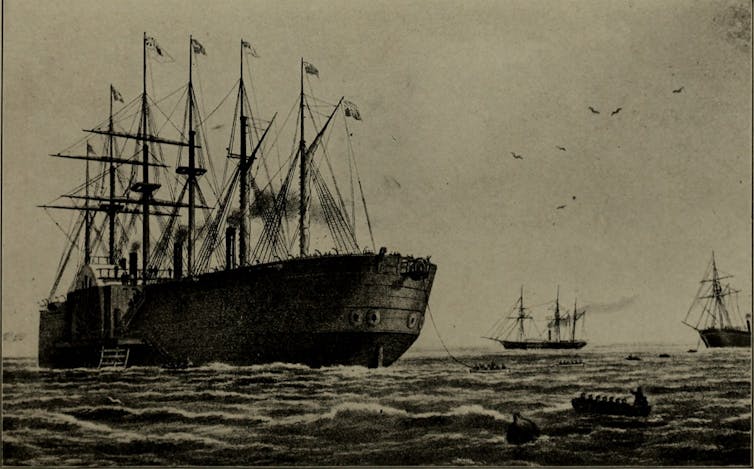

The international communications network originated with the telegraph. Terrestrial cables created the first national networks in the 1840s; submarine cables began traversing the Atlantic in the 1870s and by 1900 crossed the Pacific and Indian oceans. For the first time in history, communication – even to distant continents – was no longer tethered to the speed of human movement.

But to make a global network, states had to link their national networks together. In the 1860s, European states established the International Telegraph Union to oversee that technical work.

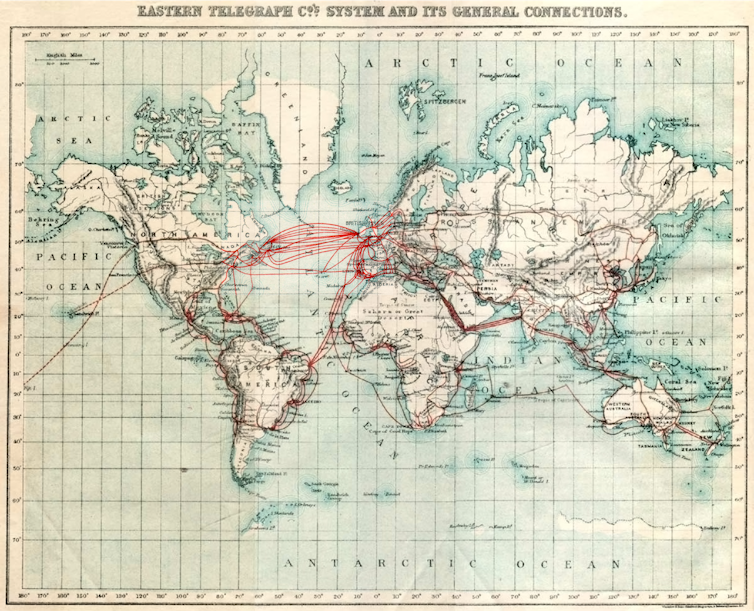

The ITU’s first task was to ensure that telegraph cable technologies were universally compatible, so that a message from any nation could be sent to any other nation. Second, it regulated costs and rates of network use. And after the ITU became responsible for regulating radio broadcast in the 1930s, it was tasked with assigning portions of the broadcast spectrum to states, which then distributed the frequencies among public and private radio companies.

These three tasks facilitated the movement of information that we often associate with the creation of the modern global information network.

Postwar promise

After World War II, it wasn’t just the physical equipment of international telecommunications that was in disarray. Most nations believed strongly that one of the war’s root causes was the international community’s failure to regulate the global flow and quality of information. The ITU had made a global network possible – but what good was that network if it helped to circulate fascistic propaganda and ignite world war?

Observers insisted that to avoid World War III, the newly formed United Nations would have to supplement the ITU by considering not just the technical elements of communication but the content of the information sent and received. They wanted an international organization to address censorship, misinformation and incitement to violence, in particular. At its very first meeting in January 1946, the U.N. General Assembly called for a global conference on “Freedom of Information and the Press.”

But the resulting conference, in 1948, revealed deep fissures over what “freedom of information” meant in practical terms. The U.S. and most of Western Europe wanted to guarantee Western news and telecommunications firms’ freedom to set up networks wherever and however they saw fit; journalists’ freedom of movement; and uniformly low, standardized telegraph rates for press use.

The developing countries, however, wanted to address the global inequality baked into international telecommunications and information flows. In 1938, for instance, U.S. companies and the British and French government-owned telecommunications companies controlled more than 96% of the telegraph cables that connected the world – much of which was still colonized. Four news agencies enjoyed a monopoly over international news: the U.S.’s Associated Press, Britain’s Reuters, France’s Havas and (until 1939) Germany’s Wolff. In 1946-47, four of every 10 telegraphs sent internationally came from the U.S. alone.

Developing nations therefore sought measures that would bring more equality to international communications: making access to information a human right, holding international journalists and news agencies accountable for biased or untrue reporting and creating international funds to develop poorer nations’ telecommunications and news industries.

Shifting power

The U.S. State Department was scandalized by suggestions that press rights should be tempered with some form of international accountability, or that truly free information flows would require addressing global inequality. U.S. representatives to the U.N. played a leading role in quashing the freedom of information question altogether. The Human Rights Sub-Commission on Freedom of Information and the Press was disbanded entirely, and the ITU continued its exclusively technological responsibilities, reserving only nominal sums to invest in poorer nations’ telecommunications development.

But as colonies won their independence in the 1950s and ’60s, they joined the U.N. and ITU as voting members. Those developing countries soon commanded a voting majority in both organizations, fundamentally shifting the balance of power. Proposals to curtail the overwhelming telecommunications power of the U.S. and its allies threatened to gain influence.

In response, the U.S. began to evade and undermine the ITU as a telecom regulator, going so far as to create an entirely separate organization, Intelsat, to administer satellite communications in the 1960s. Originally admitting members only by invitation, and basing voting power in financial contributions, Intelsat blocked most poorer and post-colonial nations out of early satellite development.

The U.S. also worked to limit the ITU’s jurisdiction over new data networks in the 1970s and 1980s, arguing that multinational corporations should be allowed to set up “Value Added” networks across national borders without government oversight. This sidelined intergovernmental consensus and handed power over global telecommunications to private corporations and technical experts, who were almost exclusively based in the U.S. That structure laid the groundwork for the origins of the internet.

Sustaining global inequality

Russia’s claim that misinformation and lack of intergovernmental regulation threaten its national security is thin. But other countries have been making similar, and much more valid, claims for over 70 years. It’s crucial to distinguish between those poignant, apt criticisms of inequality, versus the Russian government’s justifications for increasing its control.

Global telecommunications systems continue to be extraordinarily unequal. Internet saturation in parts of Asia (particularly Myanmar and Sri Lanka) and much of Africa ranges from 10% to 32%.

In the absence of global regulators who might ensure accessible technical standards, fair rates and equitable development, U.S. corporations like Facebook have been able to step in to provide a branded, unregulated form of internet service to developing countries – with damaging, dangerous and even fatal results.

So as Russia co-opts valid critiques for totalitarian ends and Europe considers regulating technology companies, it is crucial that those of us who want a truly open, global internet ask the questions, sincerely and frankly:

Is the world’s most powerful and ubiquitous communication medium regulated in a way that ensures information flows are safe and fair? And what kinds of regulation would guarantee truly universal freedom of information?

If there is a silver lining in Russia’s behavior, it’s the opportunity to put those questions back on the agenda.

Sarah Nelson has received a fellowship from the Mellon Foundation.

Read These Next

US exit from the World Health Organization marks a new era in global health policy – here’s what the

The US will no longer participate in the WHO’s global influenza monitoring system – a shift experts…

3 things to know about Kevin Warsh, Trump’s nod for Fed chair

Trump’s pick to helm the Fed is well known in the financial world, but his monetary policy views have…

I’m a former FBI agent who studies policing, and here’s how federal agents in Minneapolis are underm

A policing scholar and former FBI special agent lays out the established principles of policing and…