Reclaiming video games' queer past before it disappears

Mainstream recognition of gay gamers and characters in video games has been a long time coming.

The role of video games in queer communities is finally being recognized – but it’s almost too late.

For 30 years, GLAAD, a leading advocate for LGBTQ visibility in the media, has honored TV shows that positively represent LGBTQ people – and along the way has expanded its attention to include other genres, such as English language film, journalism, theater and Spanish language media. The 2019 GLAAD Media Awards will, for the first time, recognize video games with LGBTQ characters.

As someone who has studied LGBTQ issues in games since 2005, I see this move as an important historical shift, acknowledging that games are worthy of LGBTQ media activists’ attention. When I started my career, I had to convince people that there even were LGBTQ game content, players or creators to be studied. Now I’m the curator of an entire archive of games with LGBTQ content dating back to 1985 – and that’s just what I’ve been able to find so far.

Now, at last, a mainstream LGBTQ activist organization has found that it can’t ignore video games any longer.

A long time coming

This recognition has been a long time coming. Back in 2007, GLAAD told me it wasn’t able to focus on video game content due to resource limitations – but things have changed. Since 2009, the organization has worked to combat homophobia in online spaces. And in 2015 GLAAD honored the game “Dragon Age: Inquisition” for its positive representation of LGBTQ characters.

Other LGBTQ rights organizations have also expressed interest in video games: In 2013, Electronic Arts and the Human Rights Campaign held the Full Spectrum mini-conference in New York City, where panelists discussed LGBTQ representation in games and harassment in online gaming.

For years, LGBTQ gamers have had to face homophobia in online gaming spaces, while at the same time in offline LGBTQ communities, they were looked down on and ridiculed for gaming. GLAAD’s move is one indicator that mainstream LGBTQ activism is embracing games – and gamers, or “gaymers” – as part of LGBTQ culture. There are other changes, too: Gay bars around the United States have begun hosting “gayme” nights or adding arcade machines to their spaces. These shifts help claim games as a part of mainstream and LGBTQ cultures, as well as acknowledging that LGBTQ people are part of gaming culture.

What’s already lost?

Although there is a long history of LGBTQ people working in the games industry, much of the mainstream game industry’s recognition of LGBTQ gamers – and its inclusion of game characters – is a result of the recent exponential growth in independently produced queer games, which started around 2012.

In particular, games that represented the everyday lives of transwomen, like Merritt Kopas’s “Lim,” Anna Anthropy’s “Dys4ia” and Mattie Brice’s “Mainichi,” garnered critical attention for the way they questioned how games are expected to work and whom they are expected to represent. As in other media industries, attention to those titles helped the industry see the possibilities, and value, of representing LGBTQ people in video games. As games researcher Brendan Keogh wrote: “What the ever increasing number of creators of the queer games scene are showing the rest of us is that ‘games’ is a living tree, and as more and more people start making games that are important to them, the branches of that tree will start to grow in all kinds of new and exciting directions.”

My ongoing project the LGBTQ game archive helps chart that history, showing that LGBTQ content in games is not new. The archive’s master list includes more than 1,200 games spanning almost four decades. As early as the 1980s, and possibly even earlier, there were games including LGBTQ characters – across genres, platforms and, certainly, production quality.

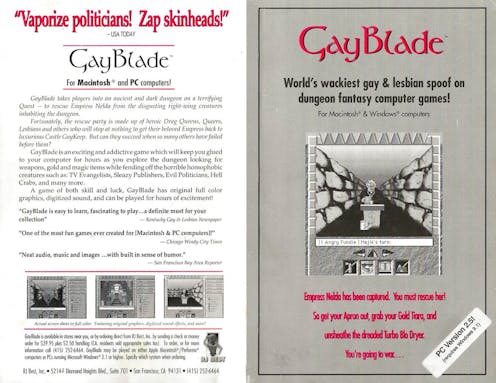

“Caper in the Castro,” which came out in 1989, and 1992’s “GayBlade” were both independently produced and had received some media coverage when they were released. Yet until I began my research, they had both been largely forgotten. “Foobar vs. the DEA,” a 1996 game about a gay superhero rescuing his boyfriend from a federal agency, was only added to my list because someone submitted it via email to the archive. It likely would have been forgotten otherwise, as it had not yet been included in any other documentation of LGBTQ game history.

Moreover, even recent indie games, including “Lim” and “Dys4ia,” are no longer online for a variety of reasons. Some queer creators have taken down their games because of harassment. Others found their free games were being overused by institutions that could rightly pay for them, and still other designers felt attention on those projects obscured their other or newer work.

Yet, independent games are not alone in their notable or nuanced forms of LGBTQ representation. In 1995’s “Orion Conspiracy,” the player’s character is investigating the murder of his son, who it turns out was a gay man. Just this year, Sony released a trailer for its new game “The Last of Us Part II,” featuring the player character Ellie dancing with and kissing another girl. LGBTQ characters have certainly moved more toward center stage in games over the last three decades. The archive also contains games that represented LGBTQ people in less flattering light, though on the whole the portrayals are not as offensive as people might expect.

As mainstream respectability rises, however, I have also seen a decline in the number of LGBTQ-gamer internet communities like those I used to research. Many of them aren’t even online anymore, lost to history, like even earlier groups that were never studied or documented at all. Social media platforms like reddit, Twitter and Tumblr increasingly serve as hubs rather than dedicated forums. Even as we work to preserve games, it’s also important to preserve the spaces for the LGBTQ people who have always made and played games.

Adrienne Shaw receives funding from Refiguring Innovation in Games (York University, Toronto Canada) and has received funding from the Temple University Digital Scholarship Center for work on the LGBTQ game archive. Research cited here was also funded by the Annenberg School for Communication at the University of Pennsylvania.

Read These Next

Violent aftermath of Mexico’s ‘El Mencho’ killing follows pattern of other high-profile cartel hits

Members of the Jalisco New Generation Cartel have set up roadblocks and attacked property and security…

What is Bluetooth and how does it work?

Did you know that your wireless earbuds contain a tiny radio transmitter?

How transparent policies can protect Florida school libraries amid efforts to ban books

Well-designed school library policies make space for community feedback while preserving intellectual…