Why did the flu kill 80,000 Americans last year?

Part of the problem was a mismatch between the influenza strains circulating and the vaccine available. Here's how annual flu shots are formulated.

The 2017-2018 flu season was historically severe. Public health officials estimate that 900,000 Americans were hospitalized and 80,000 died from the flu and its complications. For comparison, the previous worst season from the past decade, 2010-2011, saw 56,000 deaths. In a typical season, 30,000 Americans die.

So why was the 2017-2018 season such a bad year for flu? There were two big factors.

First, one of the circulating strains of the influenza virus, A(H3N2), is particularly virulent, and vaccines targeting it are less effective than those aimed at other strains. In addition, most of the vaccine produced was mismatched to the circulating A(H3N2) subtype.

These problems reflect the special biology of the influenza virus and the methods by which vaccines are produced.

Flu virus is a quick change artist

Influenza is not a single, static virus. There are three species – A, B and C – that can infect people. A is the most serious and C is rare, producing only mild symptoms. Flu is further divided into various subtypes and strains, based on the viral properties.

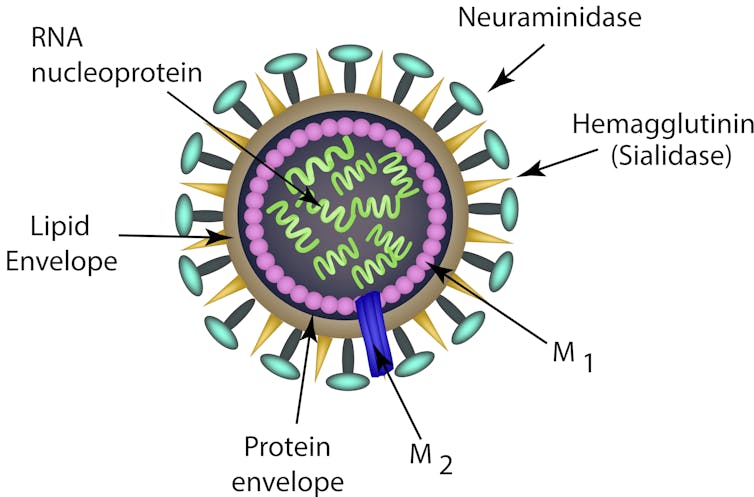

Viruses consist of protein packages surrounding the viral genome, which, in the influenza virus, consists of RNA divided into eight separate segments. The influenza virus is enveloped by a membrane layer derived from the host cell. Sticking through this membrane are spikes made up of the proteins haemagglutinin (HA) and neuraminidase (NA), both of which are required for the virus to successfully cause an infection.

Your immune system reacts first to these two proteins. Their properties determine the H and N designations of various viral strains – for instance, the H1N1 “swine flu” that swept the globe in 2009.

Both HA and NA proteins are constantly changing. The process that copies the viral RNA genome is inherently sloppy, plus these two proteins are under strong pressure to evolve so they can evade attack by the immune system. This evolution of the HA and NA proteins, called antigenic drift, prevents people from developing lasting immunity to the virus. Although the immune system may be prepared to shutdown previously encountered strains, even slight changes can require the development of a completely new immune response before the infected person becomes resistant. Thus we have seasonal flu outbreaks.

In addition, various subtypes of influenza A infect animals, the most important of which, for humans, are domestic birds and pigs. If an animal is simultaneously infected with two different subtypes, the segments of their genomes can be scrambled together. Any resulting virus may have new properties, to which humans may have little or no immune defense. This process, called antigenic shift, is responsible for the major pandemics that have swept the world in the last century.

Forecasting flu, producing vaccine

Against this background of antigenic change, every year the World Health Organization predicts which strains of flu virus will be circulating during the next flu season, and vaccines are formulated based on this information.

In 2017-2018 the vaccine was directed against specific subtypes of A(H1N1), A(H3N2) and B. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention estimates that this vaccine was 40 percent effective in preventing influenza overall. But, significantly, it was only 25 percent effective against the especially dangerous A(H3N2) strain. This mismatch probably reflects the way most of the vaccines are produced.

The common way of producing influenza vaccine starts by growing the virus in fertilized chicken eggs. After several days, the viruses are harvested, purified and inactivated, leaving the surface proteins, HA and NA, intact. But, when the virus is grown in eggs, individual viruses with changes in the HA protein that increase its ability to bind to chicken cells can grow better and thus become more common.

When people receive vaccines produced from these egg-adapted viruses, their immune system learns to target the egg-influenced HA proteins and may not react to the HA proteins on the viruses actually circulating in humans. Thus, the virus used to produce much of the 2017-2018 vaccine provoked an immune response that did not fully protect against the A(H3N2) virus circulating in the population – although it may have lessened the severity of the flu.

Small improvements and a universal vaccine

Scientists are on the hunt for a better way to protect the world’s population from influenza.

Two new vaccines that do not use egg-grown viruses are currently available. One, a vaccine made from viruses grown in mammalian cells, proved in preliminary studies to be only 20 percent more effective against A(H3N2) than egg-produced vaccine. The other, a “recombinant” vaccine consisting of only the HA proteins, is produced in insect cells, and its effectiveness is still being evaluated.

The ideal solution is a “universal” vaccine that would protect against all influenza viruses, no matter how the strains mutate and evolve. One effort relies on the fact that flu’s HA protein “stalk” is less variable than the “head” that interacts with the host cell surface; but vaccines made from a cocktail of HA protein “stalks” have proved disappointing so far. A vaccine composed of two proteins internal to the virus, M1 and NP, which are much less variable than surface-exposed proteins, is in clinical trials, as is another vaccine made up of a proprietary mixture of pieces of viral proteins. These vaccines are designed to stimulate the “memory” immune cells that persist after an infection, possibly providing lasting immunity.

Will the 2018-2019 flu season be as bad?

Based mainly on the recent flu season in South America, the World Health Organization recommended changing the A(H3,N2) subtype in the vaccine to one that better matches last year’s circulating A(H3,N2). They also recommended changing the B subtype to one that appeared in the U.S. late in the 2017-2018 season and became increasingly common elsewhere. The WHO anticipated that the circulating A(H1N1) subtype will be the same as last year and so no change was necessary on that front. So, although the same strains will most likely be circulating, epidemiologists expect the vaccines to provide better protection.

The CDC recommends that everyone 6 months and older get a flu shot every year, but, typically, fewer than half of Americans do so. Flu and its complications can be life-threatening, particularly for the young, the old and the otherwise debilitated. Most years the vaccine is well matched to the circulating virus strain, and even a poorly matched vaccine offers protection. Plus, wide-spread vaccination stops the virus from spreading and protects the vulnerable.

The first flu death of the 2018-2019 season has already occurred – a healthy but unvaccinated child died in Florida – affirming the importance of getting the flu shot.

Patricia L. Foster receives funding from the US Army Research Office. She is affiliated with Union of Concerned Scientists and Concerned Scientists at Indiana University.

Read These Next

Violent aftermath of Mexico’s ‘El Mencho’ killing follows pattern of other high-profile cartel hits

Members of the Jalisco New Generation Cartel have set up roadblocks and attacked property and security…

Crowdfunded generosity isn’t taxable – but IRS regulations haven’t kept up with the growth of mutual

Some Americans are discovering that monetary help they received from friends, neighbors or even strangers…

What is Bluetooth and how does it work?

Did you know that your wireless earbuds contain a tiny radio transmitter?