Solving the mystery of the wimpy supernova

A massive star, with a radius 500 times that of our sun, exploded. But the supernova fizzled – it was weak and dim. Figuring out what went wrong led to insights about how rare binary star systems form.

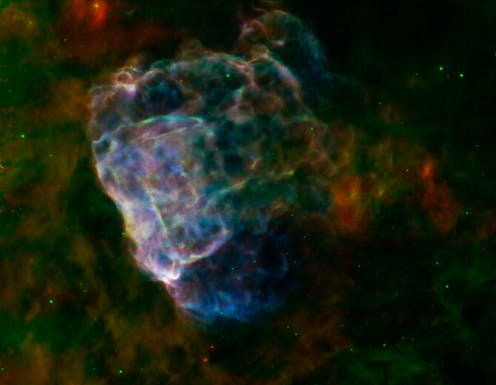

A spectacular supernova explosion, more than a billion times brighter than our sun, marked the birth of a neutron star orbiting its hot and dense companion. Now these two dense remnants are destined to spiral into each other in about a billion years, eventually merging and yielding some of the heaviest known elements in the universe.

The explosion occurred in a galaxy similar to our own Milky Way, nearly 920 million light years away. A small telescope at Palomar observatory in California detected the first photons from the supernova – named “iPTF 14gqr” – just hours after the explosion, when it was more than 10 times hotter than the surface of our sun. As the brightness of the supernova evolved during the next two weeks, an international team of astronomers used the data to trace the origin of the explosion to a massive star with a radius 500 times that of the sun.

But it wasn’t just the giant size of the star that made this discovery particularly noteworthy. What was unusual was that the star also seemed to be the lightest of all known exploding giant stars. This massive star had been robbed of nearly all of its mass, perhaps by a dense orbiting partner. When it exploded, it left behind a newborn neutron star that continued to orbit its companion.

Understanding the formation of binary star systems in which two super dense stars orbit each other has always been a puzzle. These fleeting supernovae that yield these dense binary star systems are both rare and difficult to find, because they quickly appear and disappear in the sky – about five times faster than a typical supernova.

This first observation of a “ultra-stripped” supernova, which my colleagues and I detail in a new study, not only provides insights into the formation of these systems but also reveals the final stages in the lives of these unique massive stars that have been plundered of all of their mass before they die.

Solving a longstanding mystery

Stars born with more than eight times the mass of the sun quickly run out of fuel and succumb to gravity at the end of their lives – collapsing in on themselves and exploding in a supernova. When this happens, all of the star’s outer layers – a few times the mass of the sun – are scattered.

When I started working with my advisor, Mansi Kasliwal, as a new graduate student, I decided to study supernovae that quickly fade in brightness. Mining the database of events discovered by iPTF, I came across iPTF 14gqr, a quickly fading supernova that was discovered more than a year before but whose true physical nature remained mysterious.

The data were puzzling because our preliminary models suggested this supernova was caused by the death of a giant massive star, yet the explosion in itself was quite wimpy. It ejected only a fifth of the mass of the sun, while its energy was only a tenth of a typical supernova. Where was all the missing matter and energy?

The clues indicated that the exploding star must have been stripped of nearly all of its original mass before the explosion. But what could have stolen so much matter from this giant star? Perhaps an unseen binary companion?

I started reading up about rare binary star scenarios, when I first came across the idea of “ultra-stripped supernovae.”

Ultra-stripped supernovae

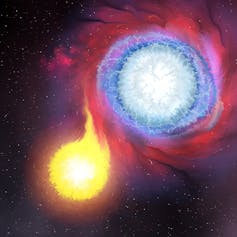

When a massive star has a dense and nearby binary companion star, the intense gravitational pull of the companion can rob its unsuspecting neighbor of nearly all its mass before it explodes – hence the term “ultra-stripped.”

The ultra-stripped supernova leaves behind a neutron star, a rapidly spinning dense stellar corpse containing a bit more than the mass of the sun crammed into a region the size of downtown Los Angeles. This neutron star is trapped in a tight orbit around its companion. The companion is possibly another neutron star, or even a white dwarf or a black hole that was formed from a massive star that died several million years before its companion.

Such binary systems have been an important field of astrophyiscal investigation for several decades. We have directly observed many such systems in our own galaxy with optical and radio telescopes. The first indirect detection of gravitational waves came from observations of a double neutron star system. More recently, the first merger of a double neutron star system was detected both by advanced LIGO and in electromagnetic waves in 2017, giving astronomers unique insights into the workings of gravity and the origin of heavy elements in the universe.

Yet, it has long remained a mystery how binary stars form. We know that neutron stars are formed in supernova explosions. But, in order to get binary neutron stars, you need a binary of two massive stars to begin. However, it requires a precise balance of forces to make sure that the binary neutron stars remain stable enough to survive the two violent explosions that create the system.

Several lines of indirect evidence suggest they are formed in a very rare class of weak ultra-stripped supernova explosions. But these faint explosions had so far escaped direct detection. This first observational evidence for an ultra-stripped supernova opens up an opportunity for understanding the formation of tight neutron star binary systems.

Scanning the heavens for infant explosions

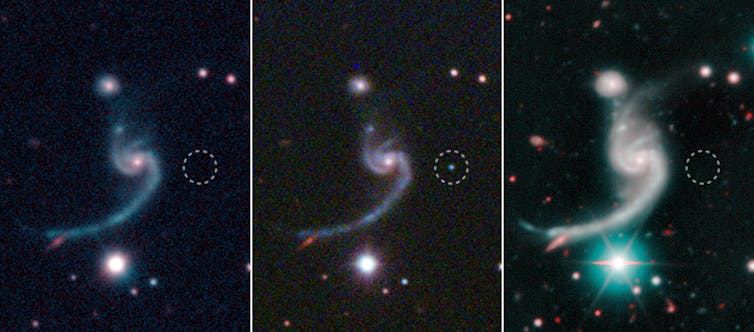

Our supernova was spotted during the intermediate Palomar Transient Factory (iPTF) survey. The automated iPTF survey used a large camera mounted on a 1-meter-sized telescope to take photos of the sky every night and scan for “new stars.” A search priority was hunting for infant supernovae and pinpointing the origin.

Whenever a new star is found, the survey robot immediately alerts on duty astronomers located in a completely different time zone to follow up. This strategy together with a global network of telescopes allowed us to catch several exploding stars in action and understand what they looked like just before they exploded. In fact, finding a rare ultra-stripped supernova moments after the explosion was a lucky coincidence!

This single event has provided us with the first insight into the mass and energy released in such explosions, the life cycle of massive stars, and the formation of binary stars. Yet, there is a lot more to be learned from a larger sample of these events.

With the Zwicky Transient Facilty– the successor of iPTF that can scan the skies 10 times faster – and a global network of telescopes called GROWTH, we hope to witness more ultra-stripped explosions, beginning a new episode in our understanding of these unique star systems.

Kishalay De does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organisation that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

Read These Next

Colleges face a choice: Try to shape AI’s impact on learning, or be redefined by it

Colleges and universities are taking on different approaches to how their students are using AI –…

Meekness isn’t weakness – once considered positive, it’s one of the ‘undersung virtues’ that deserve

The word ‘meekness’ might seem old-fashioned – and not a positive trait. But understanding its…

The greatest risk of AI in higher education isn’t cheating – it’s the erosion of learning itself

Automating knowledge production and teaching weakens the ecosystem of students and scholars that sustains…