Should all Nobel Prizes be canceled for a year?

This year's Nobel Prize for literature was nixed because of a sex scandal. Other Nobels have neglected key contributors. Should all prizes be cancelled while criteria for winning is reassessed?

If you ever meet someone who claims to have nearly won the Nobel Prize in mathematics, walk away: You’re dealing with a deeply delusional individual. While there isn’t, and has never been, a Nobel in mathematics, the desire to claim Nobel-worthiness is sensible, for no matter the field, it is the world’s most prestigious accolade.

The annual prizes are Sweden’s most sacred holiday, bringing out royalty in the arts and sciences and a worldwide audience of millions to witness an event featuring the pomp and circumstance typically associated with the naming of a new pope. Indeed, the prizes are so important to Sweden’s national identity that the king of Sweden recently took the unprecedented step of canceling the Nobel Prize in literature for 2018. What would cause King Gustaf to take such an extraordinary step? Simply put, he did so for the same reason that Alfred Nobel founded the awards to begin with: public relations.

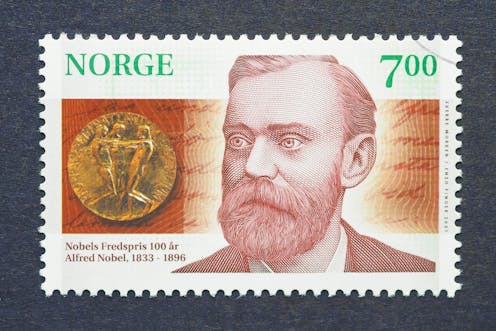

Chemist and inventor Alfred Nobel was once called “the merchant of death” for his arms dealership’s role in “killing more people faster than ever before.” To rehabilitate the Nobel name, Alfred created the eponymous prizes with a mission that the awards be “for the benefit of mankind.”

King Gustaf wisely decided that the literature Nobel take a one-year hiatus to investigate the allegations of horrific sexual misconduct by a key member of the committee that awards the prize in literature. This “stand-down” period will hopefully also allow for a reevaluation of the process by which the prizes are awarded.

While the two science prizes, in chemistry and physics, have so far not succumbed to scandal, they have had their fair share of controversy. (See Haber’s chemistry Nobel for the invention of, and later advocacy for, chemical weapons.) Still, I believe it might behoove the Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences to take a year off as well.

As an astrophysicist and an invited nominator of Nobel laureates in years past, I have studied the prize and the organization that awards them. My investigations revealed a bevy of biases that still remain within the esteemed physics prize (my specialization). If it were to “stay the course,” I fear the prestige of the Nobel, and perhaps the public’s perception of science itself, could be irreparably harmed.

Eyes on the prize

To win science’s top prize an individual must meet three main criteria, according to Alfred Nobel’s will. First they must make the most important invention or discovery in physics or chemistry. Secondly, it should be made during the previous year. And the final requirement is that it benefits all of mankind. This last outcome is the most nebulous and subjective – and frequently violated. How can the degree of the worldwide beneficence of a scientific discovery be adequately judged?

For example, given the enormous stockpiles of nuclear weapons around the world, is nuclear fission, the winning achievement of the 1944 Nobel Prize in chemistry awarded to Otto Hahn, and not to his female collaborator Lise Meitner, of sufficient benefit to warrant a Nobel?

And what about the lobotomy? This discovery, rewarded with the 1949 Nobel Prize in physiology, caused widespread and disastrous outcomes until it was banned a decade later. Gustav Dalen’s lighthouse regulator, awarded the prize in 1912, didn’t exactly enjoy the longevity of many subsequent prizes.

Even some recent prizes have raised eyebrows. Corruption charges brought up in 2008 threatened to sully the reputation of the Nobel Committee for Physiology or Medicine after drug company AstraZeneca allegedly influenced the selection of that year’s laureate for its own gain.

This points to another issue with the prize: It can misrepresent the way science is done. Science is a team sport, and no one truly goes to Stockholm alone. Yet the current restriction to at most three laureates distorts the perception of science by reinforcing the layperson’s impression that science is done by “lone geniuses” – typically “white, American males” – working without vast support networks behind them.

And what if, in contrast to these scientific innovations, the Nobel Prize itself harms rather than helps mankind, or at least the slice of it devoted to the sciences?

Nobel-worthiness?

While it’s true that Nobel’s titular prize bequeathed a fortune to scientists, activists, physicians and writers, scientists are rarely impelled to their trade for personal enrichment. In fact, science prizes such as the Templeton and Breakthrough are worth far more than the 9 million Kroner, or about US$983,000, cash purse of the Nobel Prize. Some physicists speculate that every winner of these more munificent awards would gladly forgo the extra cash for a Nobel. But Alfred Nobel’s intent wasn’t to swell scientists’ wallets. Instead, he wanted to bring attention to their beneficial work and incentivize new inventions. In this regard, the Nobel Prize has vastly exceeded Alfred’s modest expectations.

It wasn’t always this way. When the inaugural Nobel Prizes were first awarded in 1901, Wilhelm Röntgen, who won the physics prize for his discovery of X-rays, which surely improved the lives of billions around the world, was so unmoved by the accolade that he didn’t even show up to collect his medallion.

Yet, by the mid-1900s, Burton Feldman claims science became “increasingly incomprehensible to the public…when the media began its own expansion and influence.” These factors conspired to elevate the stature of the Nobel Prize along with the prominence of the laureates who are bestowed it.

Generally, most of my colleagues believe that Nobel winners in chemistry and physics deserved their prizes. Yet, is it the scientist laureates, all mankind, or the Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences – the entity charged with laureate selection – that benefits the most from the Nobel Prize?

A noble vision

The Nobel Prizes have seen many radical changes in nearly a dozen decades since they were first awarded. Despite their lofty status, my investigation into the history of the Nobel Prizes shows that they have not always lived up to the objective of benefiting mankind.

A lawsuit by Alfred Nobel’s great grandnephew, Peter Nobel, alleging use of the Nobel name for political purposes forced a name change: The prize formerly known as “the Nobel Prize in Economics” – a prize not endowed by Alfred – bears the winsome new title “The Sveriges Riksbank Prize in Economic Sciences in Memory of Alfred Nobel.”

Peace prize winners have sued the Nobel Foundation over grievances in the awardees past, including leaders considered by some to be terrorists, such as Yassir Arafat, or to be warmongers like Henry Kissinger.

While the two physical science prizes have not been plagued by the horrific allegations being brought against the literature prize, they are hardly the redoubts of gender equality: Fewer than 1 percent of the prizes in the sciences have gone to women.

I suggest that it’s time that all the Nobel Prizes, including the science prizes, take a year off to reevaluate and reflect on Alfred Nobel’s lofty vision.

Resurrecting the Nobel

How can a yearlong hiatus restore the Nobel Prizes to their past luster? First off, a reevaluation of the mission of the prizes, especially the stipulation that they benefit all mankind, should be paramount.

We need to revise the statutes, untouched since 1974, to allow for new prizes and rectify past injustices. This could be achieved by allowing both posthumous Nobels, and prizes for past awards that failed to recognize the full cohort of discoverers. Unless we do so, the Nobels misrepresent the actual history of science. Examples of such omissions, unfortunately, abound. Ron Drever died mere months before he likely would’ve won the 2017 Nobel Prize in physics. Rosalind Franklin lost her fair share of the 1962 Nobel Prize in physiology or medicine. Lise Meitner was denied her status as a 1944 Nobel Prize winner in chemistry for nuclear fission, which was awarded solely to her collaborator Otto Hahn. Jocelyn Bell, discoverer of pulsars, lost her Nobel Prize to her Ph.D. advisor. Many others – mostly women – living and deceased had also been overlooked and ignored.

To initiate the reform process, with help from colleagues and interested laypeople, my colleagues and I have established a new online advocacy forum that encourages the Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences to rectify past wrongs, prevent old mistakes from causing new harm, and more accurately reflect the broad panorama that is modern science. The Losing The Nobel Prize forum is open to scientists and nonscientists alike to submit proposals to reform and improve the Nobel Prizes.

Thoughtful action now is crucial and has tremendous potential far beyond academia. Revisiting and revising the Nobel Prize process, correcting past mistakes and making the process more transparent in the future will redound to the benefit of all mankind, reinstating the Nobel to its legendary stature.

Brian Keating receives funding from NSF, Simons Foundation and Heising-Simons Foundation.

Read These Next

Violent aftermath of Mexico’s ‘El Mencho’ killing follows pattern of other high-profile cartel hits

Members of the Jalisco New Generation Cartel have set up roadblocks and attacked property and security…

Crowdfunded generosity isn’t taxable – but IRS regulations haven’t kept up with the growth of mutual

Some Americans are discovering that monetary help they received from friends, neighbors or even strangers…

What is Bluetooth and how does it work?

Did you know that your wireless earbuds contain a tiny radio transmitter?