Lesson from Brazil: Museums are not forever

It's a comforting falsehood that once an artifact joins a museum's collection, it's safe for eternity. Museums face many foes in the fight to preserve – a lack of funds might be the biggest.

We now know what history going up in flames looks like.

On Sept. 2, the National Museum of Brazil lit up Rio de Janeiro’s night sky. Perhaps started by an errant paper hot air balloon landing on the roof or a short circuit in a laboratory, the fire gutted the historic 200-year-old building. Likely gone are a collection of resplendent indigenous ceremonial robes, the first dinosaur found in South America, Portuguese royal furniture, ancient Egyptian mummies, a vast library and so much more. In six hours, an estimated 18 million artifacts were turned to smoke and ash.

The images of the hollowed-out museum are a living nightmare for a curator like me. I know that most museum collections are truly irreplaceable. But, for me, the fire is also a vital reminder that the greatest dangers to humanity’s collective heritage are not natural disasters but human ones.

There’s an important lesson for all of us in the fire’s embers.

The perils museums face

A museum presents itself as permanent and timeless. It’s why so many sport Greek columns, sterile white walls and clean objects under clear glass. The message is that the museum and its treasures should exist beyond the fleeting moment of our visit – connecting past, present and future. Whether displaying dinosaurs or dodos, art or archaeology, the museum is our bank vault for the world’s natural wonders and human achievements. The museum aspires to be a fortress against time.

The reality is that time is inexorable and relentless. Museums are locked in a constant struggle against decay and an almost absurdly wide-ranging array of natural and human threats. There’s even a formal list of the evil-sounding “agents of deterioration” that museums use to evaluate risks to their collections, ranging from bugs to temperature to water to fire.

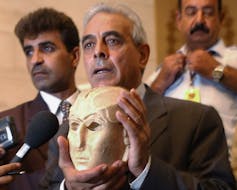

These risks are constantly evolving. War might turn a museum overnight into a looter’s paradise, as in the case of the National Museum of Iraq. Market forces or colonial revenge may spur thieves to steal artifacts, as recently seen with a pandemic of thefts of Chinese art. Some are even adding climate change to the menaces facing collections, such as the Bass Museum along Miami Beach, as it prepares for rising sea levels.

For museum curators, a terrifying range of hazards could devastate the treasures we are appointed to safeguard. Tragically, fire has long been at the top of the list. As early as 1865, the Smithsonian in Washington, D.C. – “America’s attic,” as it is famously known – caught aflame, resulting in what was then called a “national calamity.” In more recent years, infernos destroyed Madagascar’s royal palace museum, Delhi’s natural history museum and a history museum in Washington state, which housed rare artifacts from the late musician Kurt Cobain.

Despite the known risk of fire, reports suggest that Brazil’s National Museum was woefully unprepared. It apparently lacked a fire suppression system. Nearby fire hydrants went dry.

The spark that started the fire was perhaps an unforeseen event, but the conflagration that followed was not.

Collections don’t care for themselves

Most hazards that endanger museums can be mitigated. Conservation programs can hunt artifact-eating bugs, storage rooms can control temperature and humidity, security systems can prevent burglary and more. But implementing such protections requires serious resources.

By all accounts, this is where Brazil’s caretakers failed. As a national museum, Brazil’s elected officials were responsible for directing the appropriate funds to the museum. Instead, they underfunded the museum and allowed it to fall into disrepair. With the proper buildings and equipment, Brazil’s museum fire would likely not have been so disastrous.

Such indifference is not limited to Brazil. For example, a 2016 report found that Canada’s six national museums are underfunded by about US$60 million each year. In the United States, President Trump’s 2019 fiscal year budget sought to entirely eliminate three vital federal agencies – the National Endowment for the Humanities, National Endowment for the Arts and Institute of Museum and Library Services – that preserve much of the country’s cultural heritage in museums. Even before Trump, all of these programs have had relatively stagnant funding for years.

From Brazil, those holding the purse strings on citizens’ behalf must learn that museums are not forever. Collections are never permanently safe. They require focused investments and proactive stewardship to ensure their survival long into the future. Otherwise, it’s only a matter of time before the next fire.

Chip Colwell has received funding from the National Endowment for the Humanities, and is participating on projects funded by the Institute of Museum and Library Services. He is also a senior curator of anthropology at the Denver Museum of Nature & Science.

Read These Next

As war in Ukraine enters a 5th year, will the ‘Putin consensus’ among Russians hold?

Polling in Russia suggests strong support for President Vladimir Putin. Yet below the surface, popular…

Supreme Court rules against Trump’s emergency tariffs – but leaves key questions unanswered

The ruling strikes down most of the Trump administration’s current tariffs, with more limited options…

Trump administration axed nutrition education program that saved more money than it cost, even as go

Every dollar spent on community health education through SNAP-ED saved an estimated $10.64 in Medicaid…