Gender is personal – not computational

It can be unpleasant to be mistaken for someone of a different gender. When an algorithm does it secretly, it's even more concerning – especially for transgender and gender-nonconforming people.

Imagine walking down the street and seeing advertising screens change their content based on how you walk, how you talk, or even the shape of your chest. These screens rely on hidden cameras, microphones and computers to guess if you’re male or female. This might sound futuristic, but patrons in a Norwegian pizzeria discovered it’s exactly what was happening: Women were seeing ads for salad and men were seeing ads for meat options. The software running a digital advertising board spilled the beans when it crashed and displayed its underlying code. The motivation behind using this technology might have been to improve advertising quality or user experience. Nevertheless, many customers were unpleasantly surprised by it.

This sort of situation is not just creepy and invasive. It’s worse: Efforts at automatic gender recognition – using algorithms to guess a person’s gender based on images, video or audio – raise significant social and ethical concerns that are not yet fully explored. Most current research on automatic gender recognition technologies focuses instead on technological details.

Our recent research found that people with diverse gender identities, including those identifying as transgender or gender nonbinary, are particularly concerned that these systems could miscategorize them. People who express their gender differently from stereotypical male and female norms already experience discrimination and harm as a result of being miscategorized or misunderstood. Ideally, technology designers should develop systems to make these problems less common, not more so.

Using algorithms to classify people

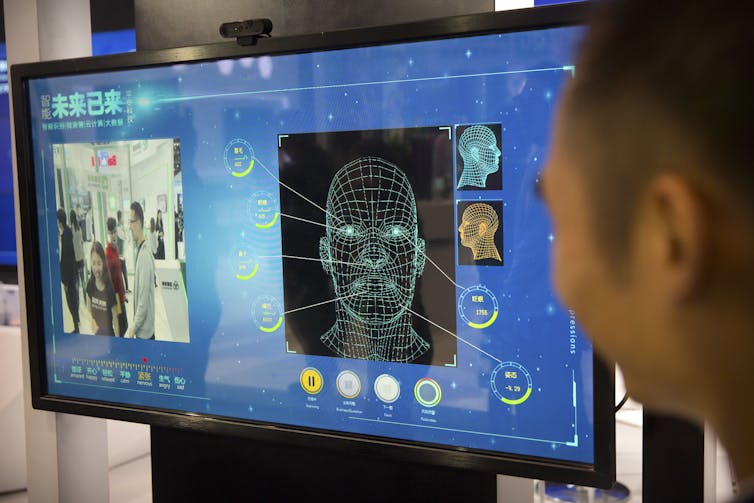

As digital technologies become more powerful and sophisticated, their designers are trying to use them to identify and categorize complex human characteristics, such as sexual orientation, gender and ethnicity. The idea is that with enough training on abundant user data, algorithms can learn to analyze people’s appearance and behavior – and perhaps one day characterize people as well as, or even better than, other humans do.

Gender is a hard topic for people to handle. It’s a complex concept with important roles both as a cultural construct and a core aspect of an individual’s identity. Researchers, scholars and activists are increasingly revealing the diverse, fluid and multifaceted aspects of gender. In the process, they find that ignoring this diversity can lead to both harmful experiences and social injustice. For example, according to the 2016 National Transgender Survey, 47 percent of transgender participants stated that they had experienced some form of discrimination at their workplace due to their gender identity. More than half of transgender people who were harassed, assaulted or expelled because of their gender identity had attempted suicide.

Many people have, at one time or another, been surprised, or confused or even angered to find themselves mistaken for a person of another gender. When that happens to someone who is transgender – as an estimated 0.6 percent of Americans, or 1.4 million people, are – it can cause considerable stress and anxiety.

Effects of automatic gender recognition

In our recent research, we interviewed 13 transgender and gender-nonconforming people, about their general impressions of automatic gender recognition technology. We also asked them to describe their responses to imaginary future scenarios where they might encounter it. All 13 participants were worried about this technology and doubted whether it could offer their community any benefits.

Of particular concern was the prospect of being misgendered by it; in their experience, gender is largely an internal, subjective characteristic, not something that is necessarily or entirely expressed outwardly. Therefore, neither humans nor algorithms can accurately read gender through physical features, such as the face, body or voice.

They described how being misgendered by algorithms could potentially feel worse than if humans did it. Technology is often perceived or believed to be objective and unbiased, so being wrongly categorized by an algorithm would emphasize the misconception that a transgender identity is inauthentic. One participant described how they would feel hurt if a “million-dollar piece of software developed by however many people” decided that they are not who they themselves believe they are.

Privacy and transparency

The people we interviewed shared the common public concern that automated cameras could be used for surveillance without their consent or knowledge; for years, researchers and activists have raised red flags about increasing threats to privacy in a world populated by sensors and cameras.

But our participants described how the effects of these technologies could be greater for transgender people. For instance, they might be singled out as unusual because they look or behave differently from what the underlying algorithms expect. Some participants were even concerned that systems might falsely determine that they are trying to be someone else and deceive the system.

Their concerns also extended to cisgender people who might look or act differently from the majority, such as people of different races, people the algorithms perceive as androgynous, and people with unique facial structures. This already happens to people from minority racial and ethnic backgrounds, who are regularly misidentified by facial recognition technology. For example, existing facial recognition technology in some cameras fail to properly detect the faces of Asian users and send messages for them to stop blinking or to open their eyes.

Our interviewees wanted to know more about how automatic gender recognition systems work and what they’re used for. They didn’t want to know deep technical details, but did want to make sure the technology would not compromise their privacy or identity. They also wanted more transgender people involved in the early stages of design and development of these systems, well before they are deployed.

Creating inclusive automatic systems

Our results demonstrate how designers of automatic categorization technologies can inadvertently cause harm by making assumptions about the simplicity and predictability of human characteristics. Our research adds to a growing body of work that attempts to more thoughtfully incorporate gender into technology.

Minorities have historically been left out of conversations about large-scale technology deployment, including ethnic minorities and people with disabilities. Yet, scientists and designers alike know that including input from minority groups during the design process can lead to technical innovations that benefit all people. We advocate for a more gender-inclusive and human-centric approach to automation that incorporates diverse perspectives.

As digital technologies develop and mature, they can lead to impressive innovations. But as humans direct that work, they should avoid amplifying human biases and prejudices that are negative and limiting. In the case of automatic gender recognition, we do not necessarily conclude that these algorithms should be abandoned. Rather, designers of these systems should be inclusive of, and sensitive to, the diversity and complexity of human identity.

The authors do not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organization that would benefit from this article, and have disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

Read These Next

Picky eating starts in the womb – a nutritional neuroscientist explains how to expand your child’s p

While genes do influence some food preferences, positive experiences can help make new tastes easier…

As war in Ukraine enters a 5th year, will the ‘Putin consensus’ among Russians hold?

Polling in Russia suggests strong support for President Vladimir Putin. Yet below the surface, popular…

How Dracula became a red-hot lover

Count Dracula was originally a rank-breathed predator. His transformation into a tragic romantic mirrors…