Reaching rural America with broadband internet service

Many people in rural America don't have access to fast, affordable internet access. How might those communities connect to the global exchange of goods, services and ideas?

All across the U.S., rural communities’ residents are being left out of modern society and the 21st century economy. I’ve traveled to Kansas, Maine, Texas and other states studying internet access and use – and I hear all the time from people with a crucial need still unmet. Rural Americans want faster, cheaper internet like their city-dwelling compatriots have, letting them work remotely and use online services, to access shopping, news, information and government data.

With an upcoming Federal Communications Commission vote on whether cellphone data speeds are fast enough for work, entertainment and other online activities, Americans face a choice: Is modest-speed internet appropriate for rural areas, or do rural Americans deserve access to the far faster service options available in urban areas?

My work, which most recently studies how people use rural libraries’ internet services, asks a fundamental set of questions: How are communities in rural regions actually connected? Why is service often so poor? Why do 39 percent of Americans living in rural areas lack internet access that meets even the FCC’s minimum definition of “broadband” service? What policies, beyond President Donald Trump’s new executive orders, might help fix those problems? What technologies would work best, and who should be in control of them?

The wide-ranging rural internet problem

Since the dawn of the internet, rural areas of the U.S. have had less internet access than urban areas. High-speed wired connections are less common, and wireless phone service and signals are weaker than in cities – or absent altogether. Even as rural America’s wired-internet speeds and mobile-phone service have improved, the overall problem remains: Cities’ services have also gotten better, so the rural communities still have comparatively worse service.

National standards have not helped: As people, businesses and governments need and want to do more online, the FCC-set minimum data-transmission speeds for broadband service has climbed. The current standard – at least 25 megabits per second downloading and 3 megabits per second uploading – is deemed “adequate” to stream video and participate in other high-traffic online activities.

But those speeds are not readily available in rural areas. The FCC is actually considering reducing the standard, which critics say may make the rural digital divide disappear on paper, but not in real life.

Rural residents have few choices of internet service providers – or none at all. They pay higher prices for lower quality service, despite earning less than urban dwellers.

A related issue is that fewer rural Americans are online: 39 percent of rural Americans lack home broadband access – in contrast to only 4 percent of urban Americans. And 69 percent of rural Americans use the internet, compared to 75 percent of urban residents. That means less participation in the culture, society, politics and economic activity of the 21st century.

Building a nationwide internet structure

The basic problem is that high-speed internet has not yet reached huge swathes of rural America. There are two main ways to fix this problem: with wires, and without wires.

Smaller towns in rural areas typically have two options for wired connectivity. About 59 percent of all fixed broadband customers use internet provided by the local cable company. Another 29 percent get their internet over phone lines, often called digital subscriber line service, or DSL. However, older systems in rural areas aren’t upgraded as often, making them slower than those in metro areas.

A few small rural towns have fiber optic networks that are much faster, but they are exceptions.

One reason rural wired service is less available and less advanced is cost, which relates to population density. In urban communities, a mile-long cable might pass dozens, or even hundreds, of homes and businesses. Rural internet requires longer wires – and often special signal-boosting equipment – with fewer potential customers from whom to recoup the costs. Rural homeowners who complain to me that they can’t get DSL, but say the farm down the road can, are probably just a bit too far from the phone company’s networking equipment. That’s much less common in cities and towns.

Wireless options

Covering these longer distances may be easier with wireless technologies, including satellite broadband, short-distance radio links and mobile-phone data.

Satellite broadband – where a customer has an antenna that connects with an orbiting satellite linked to a faster internet connection back on Earth – is technically available anywhere in the country. But it is slower, and often more expensive, than wired broadband connections. And its connections are vulnerable to bad weather.

Radio connections can vary significantly. One type, called “fixed wireless,” requires customers to be within sight of a service tower, much like a cellphone. Speeds can be up to 20 megabits per second. Satellite broadband and fixed wireless are used mostly in rural areas, but account for less than 3 percent of the U.S. fixed broadband market.

Other options just being explored involve frequency ranges that are newly available. An approach using “white space” signals would transmit data on channels previously used by analog television broadcasters. Its signals, like TV broadcasts, can travel several miles, and are not blocked by buildings.

Another frequency range around 3.5 GHz, called “Citizens Broadband Radio Service,” could let rural internet companies use frequencies previously reserved for coastal radar – even in places far inland. But the FCC may be changing the rules to favor large telecommunications companies instead.

Mobile wireless

The fourth type of wireless internet is already quite widespread – it’s on people’s smartphones nationwide. Many people have higher-speed connections at home and use mobile data on the go. However, people who don’t have access to, or can’t afford, other internet service, often use mobile wireless service as their primary internet connection.

U.S. wireless companies’ coverage maps can be deceptive. Just because a carrier has a cell tower along an interstate highway does not mean the rest of the surrounding county also has good coverage.

In our group’s research trips to Maine in 2016 and 2017, four people had phones with four different carriers, but there were plenty of places where not a single cell service was working. We have heard tales of small towns that have acceptable signals only in very specific spots – like in the middle of a side street.

Mobile phone data service has different speeds, and is often priced by how much data and how fast it travels – though even plans labeled “unlimited data” may slow down traffic after a customer transmits or receives a certain amount. Many companies promote their fourth-generation, or 4G, networks for their potential download speeds of around 20 megabits per second. But 5 to 12 megabits per second may be far more common, especially in rural regions – making it more comparable to DSL.

Mobile companies built massive networks to serve densely populated cities, leaving less populous rural markets without comparable improvements. Some hold out hope for the next wireless-data standard, the even faster fifth-generation 5G system – but rural America may not see that service for a while.

Bringing high speeds to remote places

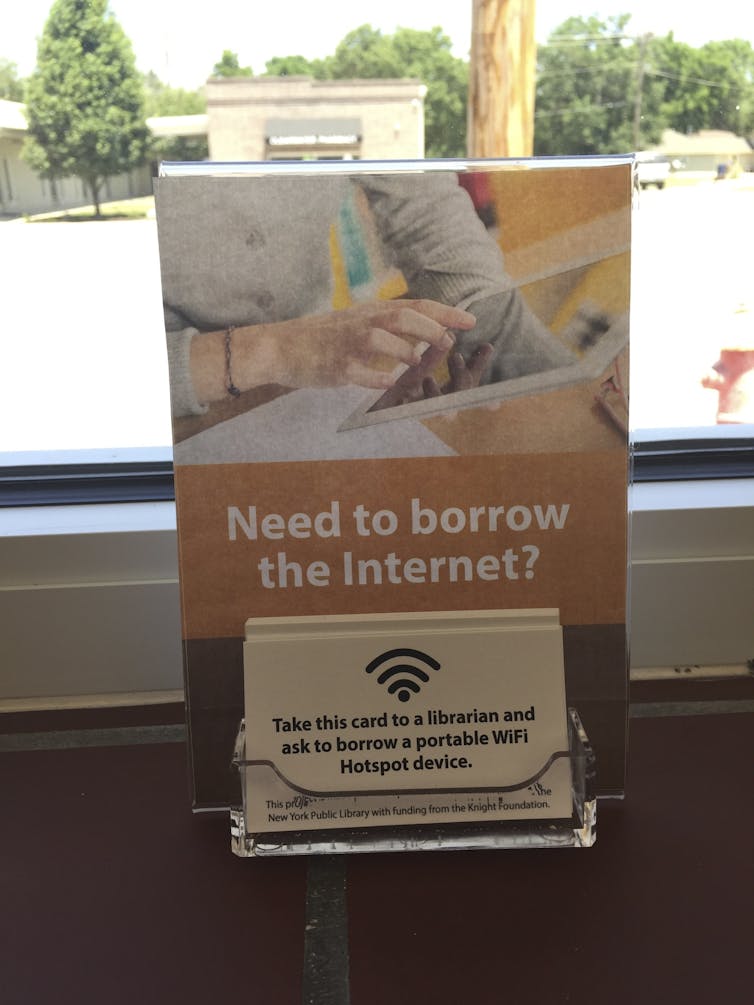

In our work, we have found a lot of people on tight budgets figuring out how to use local Wi-Fi connections to download content onto their phones, so they use (and pay for) less mobile data. Public libraries, which generally have fast and free Wi-Fi, are popular options in rural areas. Many rural librarians have told us about people in their parking lots after hours simply using the library Wi-Fi. Those connections aren’t always the fastest, but are a testament to the efforts of public libraries over many years to provide their communities’ residents with computer and internet services.

The policy debates in Washington provide the U.S. with the opportunity to choose to provide equal access to high-speed internet all across the country, or to relegate rural users to their smartphones, library parking lots and slow home connections. Real high-speed internet could change the lives of rural Americans: The FCC itself has reported that people use fixed broadband differently, and get more benefits from it than mobile data.

Fundamentally, it is a question of values. In the 1930s and ’40s, the public sentiment was that the nation would be better off if everyone had reasonably comparable electricity and telephone service. As a result, the federal government established a system of loans and grants to ensure universal access to those key utilities. To help, the FCC set up a system to charge businesses and urban customers slightly higher fees to subsidize the higher costs associated with bringing phone lines to rural areas.

The question facing the FCC and Congress – and really, the U.S. as a whole – is whether we are willing to invest in providing broadband service equitably to both urban and rural Americans. Then we need to make sure it is affordable.

Sharon Strover receives funding from The Robin Hood Foundation in New York (for research on New York's public library system hotspot program) and the federal agency Institute for Museum and Library Services (for a research project looking at rural libraries). I have worked with several federal agencies and foundations on projects relating to communication policy topics over my 30-year career.

Read These Next

Violent aftermath of Mexico’s ‘El Mencho’ killing follows pattern of other high-profile cartel hits

Members of the Jalisco New Generation Cartel have set up roadblocks and attacked property and security…

Crowdfunded generosity isn’t taxable – but IRS regulations haven’t kept up with the growth of mutual

Some Americans are discovering that monetary help they received from friends, neighbors or even strangers…

What is Bluetooth and how does it work?

Did you know that your wireless earbuds contain a tiny radio transmitter?