How citizen investigators can collaborate on crowdsourced fact-checking

A new approach can both teach critical thinking to the public and help identify and combat fake news online.

It can be hard to know what is true online. Propaganda and misinformation have a much longer history than the internet, of course. But the rapid proliferation of “fake news” on social media, and its tendency to extend into mainstream news coverage, can obscure the difference between credible information and inaccuracies.

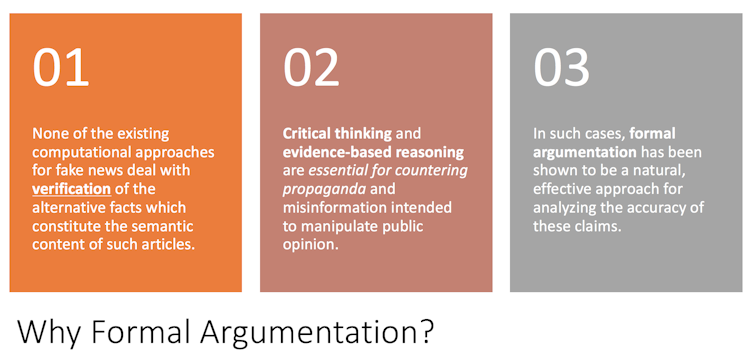

Modern attempts to combat the spread of falsehoods have focused mainly on computerized, automated tools. They flag previously identified hoaxes; or automatically detect fake news using natural language processing techniques; or track the virus-like transmission of hoaxes. However, none of them focuses on verifying the statements contained in news and opinion articles.

Research reveals that the best remedy for propaganda and misinformation intended to manipulate public opinion is helping readers engage in critical thinking and evidence-based reasoning. My team conducts research on how critical thinking emerges in online communities and has recently developed a way for groups of people to engage in collective critical reasoning. This approach can help confirm or invalidate controversial or complex statements, and explain the evaluation clearly.

Breaking down claims into components

Our method involves analyzing claims through a formal structure called argumentation. Most people dislike arguments, thinking of them as involving bickering or fighting. But formal argumentation is a method of working through ideas or hypotheses critically and systematically. One of our innovations is to allow groups of people to work through this process together, with each person handling small pieces that can be assembled into a complete evaluation of a statement or claim.

The argumentation process starts with a question. Let’s use, for an example, the question that served as the origin of the term “alternative facts.” (There is also a legal term “alternative facts,” which is different.)

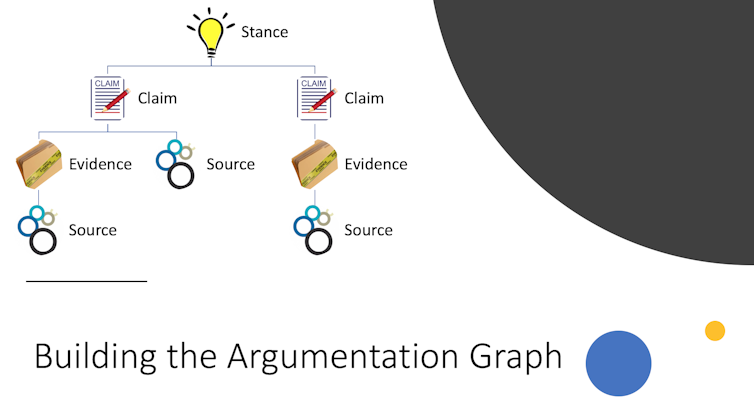

The question is, “Were the crowds larger at Donald Trump’s inauguration than at Barack Obama’s?” This question might have two possible answers, or in the terms of argumentation, “stances”: yes or no.

Each stance – for instance, a person saying “yes” – must be supported by one or more “claims.” A claim might be, “Donald Trump’s inauguration attendance can be measured by that day’s ridership numbers on the local public transit system.”

Claims are supported by “evidence” – such as “Per WMATA, the Washington area transit authority, as of 11 a.m., 193,000 trips had been taken on the city’s subway system.”

The evidence, in turn, relies upon a “source,” such as a CNN article providing that data.

Other evidence might shed additional light on the matter. For instance, that same source CNN article provides an item of evidence that gives useful context by refuting the initial stance of yes: “At the same hour in 2009, that number was 513,000, according to WMATA.”

Using our system

On our prototype website, users can create new inquiries or engage in ongoing ones. To fact-check a statement, for example, a user might post an assertion someone made in the news or on social media. Other users could then contribute related stances, claims, evidence and sources. Each addition helps flesh out the formal argument structure with additional information.

As an argument is constructed, users can examine the information presented and evaluate it for themselves. They can rate particular contributions as helpful (or unhelpful), and even rate other users themselves as reliable or less so. They can also filter arguments based upon the properties of a source, evidence, user or claim, including the emotional content. In this way, users can examine a preexisting argument and decide for themselves which stance is supported for a given set of criteria.

Providing new facts alone, however, can lead to something called the “backfire effect,” where giving people additional information can, counterintuitively, lead to users’ opinions hardening despite evidence to the contrary. Fortunately, recent research in educational psychology suggests that thinking through material can evoke emotions, such as surprise and frustration, which can mediate this backfire effect.

Our prototype system incorporates emotions as well, by letting users rate how they feel about claims. Following Plutchik’s wheel of emotion, users can rate where their feelings fall on four emotional ranges: Contented → Angry, Happy → Sad, Trust → Distrust and Likely → Unlikely. This helps us research the potential extent of the backfire effect and continue to study ways to overcome it.

Engaging the social network

We have also added a social network component to our system. Some people might want to just browse existing arguments, while others might want to contribute a claim or evidence. We organize community members to ensure that users who contribute are qualified to do so.

Viewers can ask questions and examine the arguments assembled by others. Contributors are users with some amount of expertise or background, who are authorized to add claim, evidence and source information. And moderators guide the construction of the argument, matching contributors to new questions and evaluating contributions to ensure quality.

This structure helps our system adapt to different purposes, including managing discussions among experts within a certain field or conducting threaded discussions between students and teachers in online classes. A site like the WikiTribune news platform proposed by Jimmy Wales, co-founder of Wikipedia, could use a version of our approach – perhaps with a different interface – to build and support different sections of articles. For example, WikiTribune’s reporters could be represented by contributors while their editors would be the moderators in our approach. In addition, the various parts of a story could be broken down as stances or claims in an argumentation structure when modeled using our framework.

Even existing social networking sites like Facebook could set up a section of its site for people to engage in collaborative fact-checking and help combat the spread of fake news. People could see how different groups they’re connected to build and filter these arguments, and gauge the emotional content of aspects of those arguments.

It’s not yet clear whether crowdsourcing fact-checking is the best way to verify alternative facts, and even if so, whether our approach is the best way to manage the process. But in the end, getting people to engage in evidence-based reasoning can have benefits well beyond identifying specific instances of “fake news” – it can teach users the critical thinking skills needed to detect and evaluate misinformation and fake news they may encounter in the future.

The author received funding for this research thrust variously from Amazon AWS Research Grants (Amazon), the National Endowment for the Humanities (NEH), and the National Science Foundation (NSF). In addition, we would like to thank Yolanda Gil for the collaboration and RaghuRam Rangaraju for the development effort.

Read These Next

Meekness isn’t weakness – once considered positive, it’s one of the ‘undersung virtues’ that deserve

The word ‘meekness’ might seem old-fashioned – and not a positive trait. But understanding its…

How Homeland Security’s subpoenas and databases of protesters threaten the ‘uninhibited, robust, and

It’s difficult to measure what is lost when an opinion is never voiced and impossible to catalogue…

Supreme Court rules against Trump’s emergency tariffs – but leaves key questions unanswered

The ruling strikes down most of the Trump administration’s current tariffs, with more limited options…