Artificial metacognition: Giving an AI the ability to ‘think’ about its ‘thinking’

What if an AI system could recognize when it’s confused or when to think more carefully? Researchers are working to give large language models these metacognitive abilities.

Have you ever had the experience of rereading a sentence multiple times only to realize you still don’t understand it? As taught to scores of incoming college freshmen, when you realize you’re spinning your wheels, it’s time to change your approach.

This process, becoming aware of something not working and then changing what you’re doing, is the essence of metacognition, or thinking about thinking.

It’s your brain monitoring its own thinking, recognizing a problem, and controlling or adjusting your approach. In fact, metacognition is fundamental to human intelligence and, until recently, has been understudied in artificial intelligence systems.

My colleagues Charles Courchaine, Hefei Qiu and Joshua Iacoboni and I are working to change that. We’ve developed a mathematical framework designed to allow generative AI systems, specifically large language models like ChatGPT or Claude, to monitor and regulate their own internal “cognitive” processes. In some sense, you can think of it as giving generative AI an inner monologue, a way to assess its own confidence, detect confusion and decide when to think harder about a problem.

Why machines need self-awareness

Today’s generative AI systems are remarkably capable but fundamentally unaware. They generate responses without genuinely knowing how confident or confused their response might be, whether it contains conflicting information, or whether a problem deserves extra attention. This limitation becomes critical when generative AI’s inability to recognize its own uncertainty can have serious consequences, particularly in high-stakes applications such as medical diagnosis, financial advice and autonomous vehicle decision-making.

For example, consider a medical generative AI system analyzing symptoms. It might confidently suggest a diagnosis without any mechanism to recognize situations where it might be more appropriate to pause and reflect, like “These symptoms contradict each other” or “This is unusual, I should think more carefully.”

Developing such a capacity would require metacognition, which involves both the ability to monitor one’s own reasoning through self-awareness and to control the response through self-regulation.

Inspired by neurobiology, our framework aims to give generative AI a semblance of these capabilities by using what we call a metacognitive state vector, which is essentially a quantified measure of the generative AI’s internal “cognitive” state across five dimensions.

5 dimensions of machine self-awareness

One way to think about these five dimensions is to imagine giving a generative AI system five different sensors for its own thinking.

- Emotional awareness, to help it track emotionally charged content, which might be important for preventing harmful outputs.

- Correctness evaluation, which measures how confident the large language model is about the validity of its response.

- Experience matching, where it checks whether the situation resembles something it has previously encountered.

- Conflict detection, so it can identify contradictory information requiring resolution.

- Problem importance, to help it assess stakes and urgency to prioritize resources.

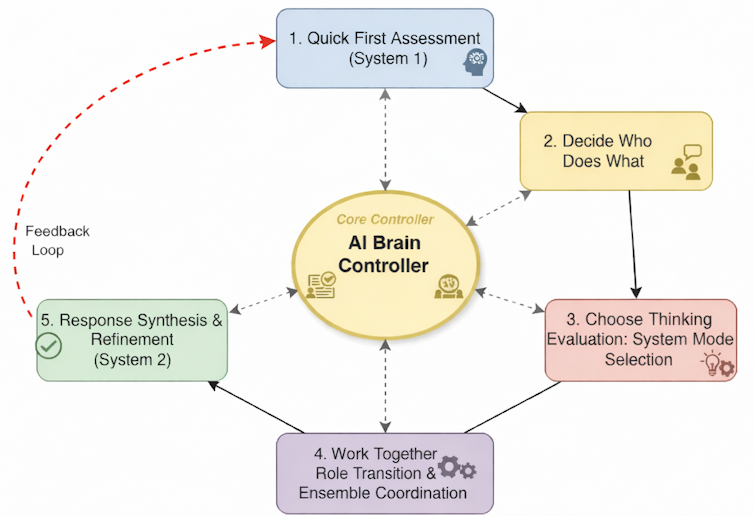

We quantify each of these concepts within an overall mathematical framework to create the metacognitive state vector and use it to control ensembles of large language models. In essence, the metacognitive state vector converts a large language model’s qualitative self-assessments into quantitative signals that it can use to control its responses.

For example, when a large language model’s confidence in a response drops below a certain threshold, or the conflicts in the response exceed some acceptable levels, it might shift from fast, intuitive processing to slow, deliberative reasoning. This is analogous to what psychologists call System 1 and System 2 thinking in humans.

Conducting an orchestra

Imagine a large language model ensemble as an orchestra where each musician – an individual large language model – comes in at certain times based on the cues received from the conductor. The metacognitive state vector acts as the conductor’s awareness, constantly monitoring whether the orchestra is in harmony, whether someone is out of tune, or whether a particularly difficult passage requires extra attention.

When performing a familiar, well-rehearsed piece, like a simple folk melody, the orchestra easily plays in quick, efficient unison with minimal coordination needed. This is the System 1 mode. Each musician knows their part, the harmonies are straightforward, and the ensemble operates almost automatically.

But when the orchestra encounters a complex jazz composition with conflicting time signatures, dissonant harmonies or sections requiring improvisation, the musicians need greater coordination. The conductor directs the musicians to shift roles: Some become section leaders, others provide rhythmic anchoring, and soloists emerge for specific passages.

This is the kind of system we’re hoping to create in a computational context by implementing our framework, orchestrating ensembles of large language models. The metacognitive state vector informs a control system that acts as the conductor, telling it to switch modes to System 2. It can then tell each large language model to assume different roles – for example, critic or expert – and coordinate their complex interactions based on the metacognitive assessment of the situation.

Impact and transparency

The implications extend far beyond making generative AI slightly smarter. In health care, a metacognitive generative AI system could recognize when symptoms don’t match typical patterns and escalate the problem to human experts rather than risking misdiagnosis. In education, it could adapt teaching strategies when it detects student confusion. In content moderation, it could identify nuanced situations requiring human judgment rather than applying rigid rules.

Perhaps most importantly, our framework makes generative AI decision-making more transparent. Instead of a black box that simply produces answers, we get systems that can explain their confidence levels, identify their uncertainties, and show why they chose particular reasoning strategies.

This interpretability and explainability is crucial for building trust in AI systems, especially in regulated industries or safety-critical applications.

The road ahead

Our framework does not give machines consciousness or true self-awareness in the human sense. Instead, our hope is to provide a computational architecture for allocating resources and improving responses that also serves as a first step toward more sophisticated approaches for full artificial metacognition.

The next phase in our work involves validating the framework with extensive testing, measuring how metacognitive monitoring improves performance across diverse tasks, and extending the framework to start reasoning about reasoning, or metareasoning. We’re particularly interested in scenarios where recognizing uncertainty is crucial, such as in medical diagnoses, legal reasoning and generating scientific hypotheses.

Our ultimate vision is generative AI systems that don’t just process information but understand their cognitive limitations and strengths. This means systems that know when to be confident and when to be cautious, when to think fast and when to slow down, and when they’re qualified to answer and when they should defer to others.

Ricky J. Sethi has received funding from the National Science Foundation, Google and Amazon.

Read These Next

Constant technology changes throw seniors a curve – and add to caregivers’ load

As devices get smarter, families and communities bear a heavier burden of technology caregiving for…

Legal refugees now face long detention after DHS reinterprets law on applying for a green card after

A new DHS policy could result in the detention of thousands of people who have lawful immigration status.

‘The Tibetan Book of the Dead’ is actually not just about death

Rooted in the Buddhist teaching of the bardo − states of ‘in-between’ − the text offers a way…