AI cannot automate science – a philosopher explains the uniquely human aspects of doing research

While AI can streamline certain parts of the scientific process, a philosopher argues that it cannot replace human expertise and collaboration.

Consistent with the general trend of incorporating artificial intelligence into nearly every field, researchers and politicians are increasingly using AI models trained on scientific data to infer answers to scientific questions. But can AI ultimately replace scientists?

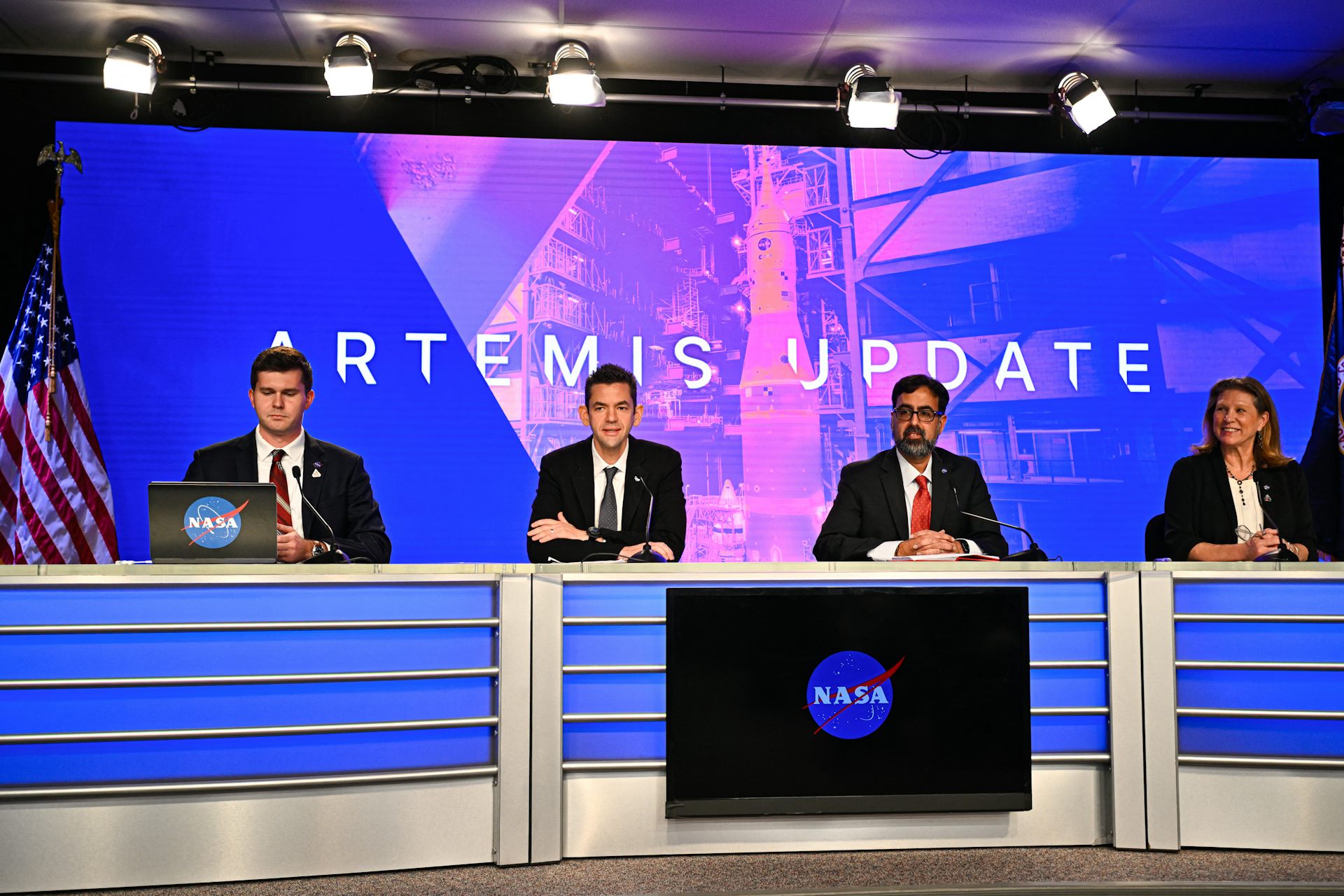

The Trump administration signed an executive order on Nov. 24, 2025, that announced the Genesis Mission, an initiative to build and train a series of AI agents on federal scientific datasets “to test new hypotheses, automate research workflows, and accelerate scientific breakthroughs.”

So far, the accomplishments of these so-called AI scientists have been mixed. On the one hand, AI systems can process vast datasets and detect subtle correlations that humans are unable to detect. On the other hand, their lack of commonsense reasoning can result in unrealistic or irrelevant experimental recommendations.

While AI can assist in tasks that are part of the scientific process, it is still far away from automating science – and may never be able to. As a philosopher who studies both the history and the conceptual foundations of science, I see several problems with the idea that AI systems can “do science” without or even better than humans.

AI models can only learn from human scientists

AI models do not learn directly from the real world: They have to be “told” what the world is like by their human designers. Without human scientists overseeing the construction of the digital “world” in which the model operates – that is, the datasets used for training and testing its algorithms – the breakthroughs that AI facilitates wouldn’t be possible.

Consider the AI model AlphaFold. Its developers were awarded the 2024 Nobel Prize in chemistry for the model’s ability to infer the structure of proteins in human cells. Because so many biological functions depend on proteins, the ability to quickly generate protein structures to test via simulations has the potential to accelerate drug design, trace how diseases develop and advance other areas of biomedical research.

As practical as it may be, however, an AI system like AlphaFold does not provide new knowledge about proteins, diseases or more effective drugs on its own. It simply makes it possible to analyze existing information more efficiently.

As philosopher Emily Sullivan put it, to be successful as scientific tools, AI models must retain a strong empirical link to already established knowledge. That is, the predictions a model makes must be grounded in what researchers already know about the natural world. The strength of this link depends on how much knowledge is already available about a certain subject and on how well the model’s programmers translate highly technical scientific concepts and logical principles into code.

AlphaFold would not have been successful if it weren’t for the existing body of human-generated knowledge about protein structures that developers used to train the model. And without human scientists to provide a foundation of theoretical and methodological knowledge, nothing AlphaFold creates would amount to scientific progress.

Science is a uniquely human enterprise

But the role of human scientists in the process of scientific discovery and experimentation goes beyond ensuring that AI models are properly designed and anchored to existing scientific knowledge. In a sense, science as a creative achievement derives its legitimacy from human abilities, values and ways of living. These, in turn, are grounded in the unique ways in which humans think, feel and act.

Scientific discoveries are more than just theories supported by evidence: They are the product of generations of scientists with a variety of interests and perspectives, working together through a common commitment to their craft and intellectual honesty. Scientific discoveries are never the products of a single visionary genius.

For example, when researchers first proposed the double-helix structure of DNA, there were no empirical tests able to verify this hypothesis – it was based on the reasoning skills of highly trained experts. It took nearly a century of technological advancements and several generations of scientists to go from what looked like pure speculation in the late 1800s to a discovery honored by a 1953 Nobel Prize.

Science, in other words, is a distinctly social enterprise, in which ideas get discussed, interpretations are offered, and disagreements are not always overcome. As other philosophers of science have remarked, scientists are more similar to a tribe than “passive recipients” of scientific information. Researchers do not accumulate scientific knowledge by recording “facts” – they create scientific knowledge through skilled practice, debate and agreed-upon standards informed by social and political values.

AI is not a ‘scientist’

I believe the computing power of AI systems can be used to accelerate scientific progress, but only if done with care.

With the active participation of the scientific community, ambitious projects like the Genesis Mission could prove beneficial for scientists. Well-designed and rigorously trained AI tools would make the more mechanical parts of scientific inquiry smoother and maybe even faster. These tools would compile information about what has been done in the past so that it can more easily inform how to design future experiments, collect measurements and formulate theories.

But if the guiding vision for deploying AI models in science is to replace human scientists or to fully automate the scientific process, I believe the project would only turn science into a caricature of itself. The very existence of science as a source of authoritative knowledge about the natural world fundamentally depends on human life: shared goals, experiences and aspirations.

Alessandra Buccella does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organization that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

Read These Next

GLP-1 drugs may fight addiction across every major substance, according to a study of 600,000 people

GLP-1 drugs are the first medication to show promise for treating addiction to a wide range of substances.

Congress once fought to limit a president’s war powers − more than 50 years later, its successors ar

At the tail end of the Vietnam War, Congress engaged in a breathtaking act of legislative assertion,…

Trauma patients recover faster when medical teams know each other well, new study finds

A new study from a Pittsburgh hospital finds that trauma patients recover faster when emergency medical…