An ultrathin coating for electronics looked like a miracle insulator − but a hidden leak fooled rese

A new study investigated the source of a leak in a ‘miracle measurement’ from 2010 – and engineers found a potential solution.

When your winter jacket slows heat escaping your body or the cardboard sleeve on your coffee keeps heat from reaching your hand, you’re seeing insulation in action. In both cases, the idea is the same: keep heat from flowing where you don’t want it. But this physics principle isn’t limited to heat.

Electronics use it too, but with electricity. An electrical insulator stops current from flowing where it shouldn’t. That’s why power cords are wrapped in plastic. The plastic keeps electricity in the wire, not in your hand.

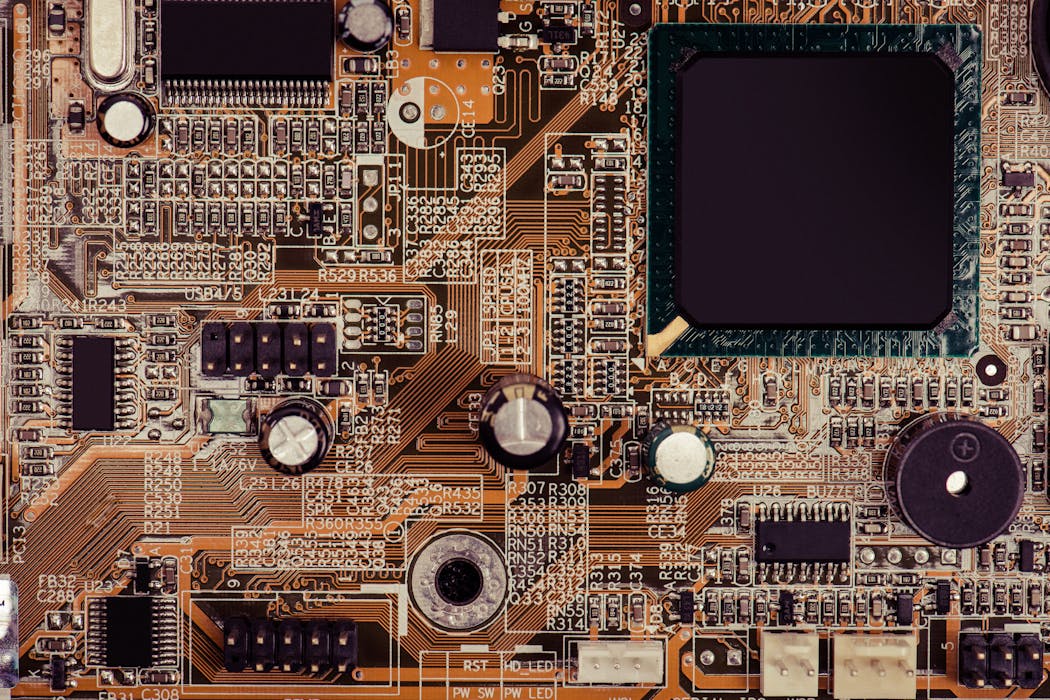

Inside electronics, insulators do more than keep the user safe. They also help devices store charge in a controlled way. In that role, engineers often call them dielectrics. These insulating layers sit at the heart of capacitors and transistors. A capacitor is a charge-storing component – think of it as a tiny battery, albeit one that fills up and empties much faster than a battery. A transistor is a tiny electrical switch. It can turn current on or off, or control how much current flows.

Together, capacitors and transistors make modern electronics work. They help phones store information, and they help computers process it. They help today’s AI hardware move huge amounts of data at high speed.

What surprises most people is how thin these insulating, current-quelling dielectrics are. In modern microchips, key dielectric layers can be only a few nanometers thick. That’s tens of thousands of times thinner than a human hair. A modern phone can contain billions of transistors, so at that scale, slimming them down by even 1 nanometer can make a difference.

As an electrical and material scientist, I work with my adviser, Tara P. Dhakal, at Binghamton University to understand how to make these insulating layers as thin as possible while preserving their reliability.

Thinner dielectrics don’t just shrink devices. They can also help store more charge. But at such scale, electronics get finicky. Sometimes what looks like a breakthrough isn’t quite what it seems. That’s why our focus is not just making dielectrics thin. It’s making them both thin and trustworthy.

What makes one dielectric better than another?

In both capacitors and transistors, the basic structure is simple: They contain two conductors separated by a thin insulator. If you bring the conductors closer, more charge can build up. It’s like two strong magnets with a sheet between them – the thinner the sheet, the stronger the pull.

But thinning has a limit. In transistors, the classic insulator silicon dioxide loses its ability to insulate at about 1.2 nanometers. At that scale, electrons can sneak through a shortcut called quantum tunneling. Enough charge leaks through that the device is no longer practical.

When materials are so thin that they start to leak, engineers have another lever. They can switch to an insulator that stores more charge without being made extremely thin. That ability is described by a metric called the dielectric constant, written as k. Higher-k materials can achieve that storage with a thicker layer, which makes it much harder for electrons to slip through.

For example, silicon dioxide has k of about 3.9, and aluminum oxide has k of about 8, twice as high. If a 1.2-nanometer silicon dioxide layer leaks too much, you can switch to a 2.4-nanometer aluminum oxide layer and get roughly the same charge storage. Because the film is physically thicker, it won’t leak as much.

The breakthrough that wasn’t

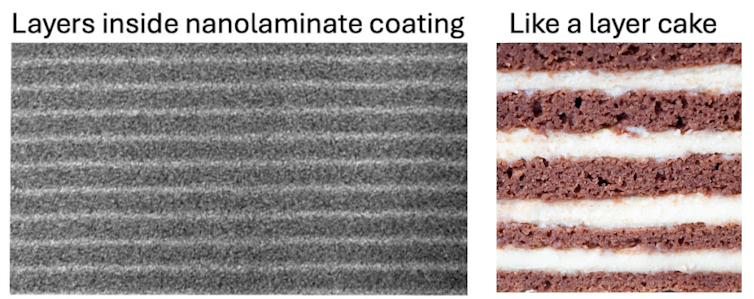

In 2010, a team of researchers at Argonne National Laboratory reported something that sounded almost impossible: They’d made an ultrathin coating that apparently had a giant dielectric constant, near 1,000. The material wasn’t a single new compound. It was a nanolaminate – a microscopic layer cake. In nanolaminates, you stack two materials in repeating A-B-A-B layers, hoping their interfaces create properties neither material has on its own.

In that work, the stack alternated aluminum oxide, with a k of about 8, and titanium oxide, with a k of about 40. The researchers built the stack by growing one molecular layer at a time, which is ideal for building and controlling the nanometer-scale layers in a nanolaminate.

When the team made each sublayer less than a nanometer, it found that the entire material was able to hold an incredible amount of charge – thus, the giant k.

The result triggered years of follow-up work and similar reports in other stacks of oxides.

But there’s a twist. In our recent study of the aluminum oxide/titanium oxide nanolaminate system, we found that the apparent giant k value was a measurement error.

In our study, the nanolaminate wasn’t acting like a clean insulator, and it was leaking enough to inflate the k value. Think of a bucket with a hairline crack: You keep pouring, and it seems like the bucket holds a lot, even though the water won’t stay inside.

Once we figured that a leak was behind the giant k result, we set out to solve the larger puzzle. We wanted to know what makes the nanolaminate leak, and what process change could make it truly insulating.

The culprit

We first looked for an obvious culprit: a visible defect. If a film stack leaks, you expect pinholes or cracks. But the nanolaminate looked smooth and continuous under the microscope. So why would a stack that looks solid fail?

The answer wasn’t in the shape, it was in the chemistry. The earliest aluminum oxide sublayers didn’t contain enough aluminum. That meant the film looked continuous, yet was still incomplete at the atomic scale. Electrons could find connected paths and escape through it. It was physically continuous but electrically leaky.

Our process to create these films, called atomic layer deposition, uses tiny, repeatable cycles. You add in two chemicals, one after the other. Each pair is one cycle. For aluminum oxide, the pair is often trimethylaluminium (TMA), which is the aluminum source, and water, which is the oxygen source. Together, they create the aluminum oxide, and one cycle adds roughly a single layer of material – about one-tenth of a nanometer. By repeating the cycles, you can grow the film to the thickness you need: about 10 cycles for 1 nanometer, 25 cycles for 2.5 nanometers, and so on.

But there’s a catch. When you deposit aluminum oxide on top of titanium oxide, the first chemical for aluminum oxide – TMA – can steal oxygen from the titanium oxide layer below. This issue removes some of the sites the aluminum source normally reacts with on the layer’s surface. So, the first aluminum oxide layer doesn’t grow evenly and ends up with less aluminum than it should have.

That problem leaves tiny weak spots where electrons can slip through and cause leakage. Once the aluminum oxide becomes thick enough – around 2 nanometers – it forms a more complete barrier, and those leakage paths are effectively sealed off.

One small change flipped the outcome. We kept the same aluminum source, TMA, but swapped the oxygen source. Instead of water, we used ozone. Ozone is a stronger oxygen source, so it can replace oxygen that gets pulled out during the TMA step. That shut down leakage paths. The aluminum oxide then behaved like a real barrier, even when it was thinner than a nanometer. With the ozone fix, the nanolaminate acted like a true insulator.

The takeaway is simple: When you’re down to a few atomic layers, chemistry can matter as much as thickness. The types of chemical compounds you use can decide whether those early layers become a real barrier or leave behind leakage paths.

Mahesh Nepal does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organization that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

Read These Next

With Artemis II facing delays, NASA announces big structural changes to the lunar program

Artemis II has been plagued by similar issues to those faced by its predecessor, leading NASA to shake…

Welcome to the ‘gray zone’ − home to nefarious international acts that fall short of outright confli

Nations are becoming adept at provocations that fall in the area between routine peacetime actions and…

Former Harvard president Summers’ soft landing after Epstein revelations is case study of economics’

Despite repeated calls for the university to revoke his tenure, the economist held onto his teaching…