Superheavy-lift rockets like SpaceX’s Starship could transform astronomy by making space telescopes

NASA, SpaceX and Blue Origin have all successfully launched superheavy-lift rockets. These massive vehicles are designed to carry a much heavier load.

After a string of dramatic failures, the huge Starship rocket from SpaceX had a fully successful test on Oct. 13, 2025. A couple more test flights, and SpaceX plans to launch it into orbit.

A month later, a rival rocket company, Blue Origin, flew its almost-as-large New Glenn rocket all the way to orbit and sent spacecraft on their way to Mars.

While these successful flights are exciting news for future missions to the Moon as well as other planets, I’ve argued for several years that these superheavy-lift rockets can also boost research in my own specialty, astronomy – the study of stars and galaxies far beyond our solar system – to new heights.

Taking the broad view

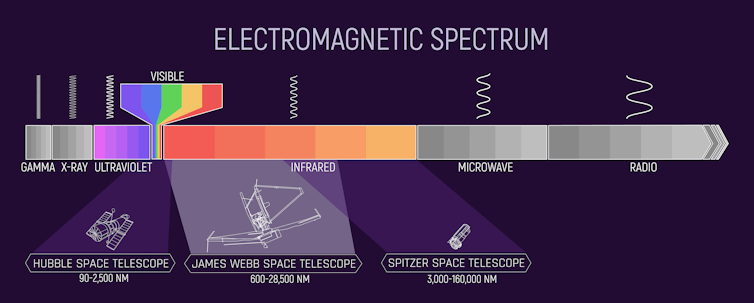

Why do I say that? Astronomy needs space. Getting above the atmosphere allows telescopes to detect vastly more of the electromagnetic spectrum than visible light alone. At these heights, telescopes can detect light at much longer and shorter wavelengths, which are otherwise blocked by Earth’s atmosphere.

To get an idea of how that has enriched astronomy, imagine listening to someone play the piano, but only in one octave. The music would sound much richer if they used the full keyboard.

With the broader spectrum in view, astronomers can see objects in the sky that are much colder than stars, but also objects that are far hotter.

How much cooler and hotter? The hottest stars you can see in visible light are about 10 times hotter than the coolest. With the whole infrared-to-X-ray spectrum, the temperatures that come into view can be 1,000 times colder or 1,000 times hotter than regular stars.

Scientists have had nearly 50 years of access to the full light spectrum with sets of increasingly powerful telescopes. Alas, this access has come at an ever-increasing cost, too. The newest telescope is the spectacular James Webb Space Telescope, which cost about US$10 billion and detects a portion of the infrared spectrum. At that forbidding price, NASA can’t afford to match Webb across the spectrum by building its full infrared and X-ray siblings.

We’ll have to wait a long time even for one more. The estimated date to launch the next “Great Observatory” is a distant 2045 and may be later. The range of notes astronomers can play will shrink, along with our views of the universe.

Escaping the trap with heavy-lift vehicles

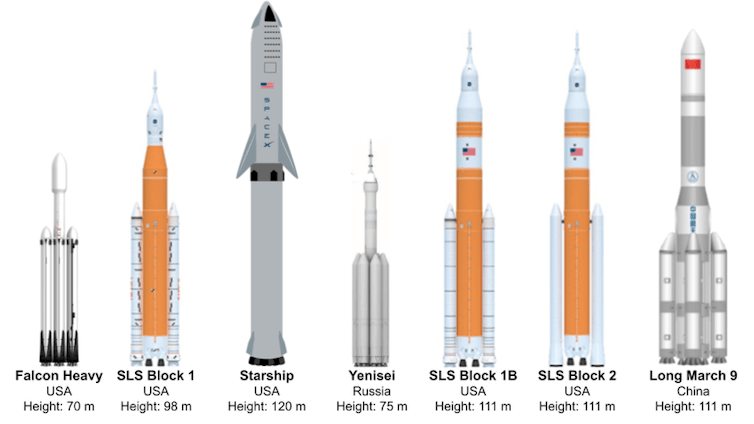

These new rockets give us a chance to escape this trap. For the same cost, they can send about 10 times more mass to orbit, and they have bodies about twice as wide, compared with the rockets that have been in use for decades.

Mass matters because telescopes contain heavy mirrors, and the bigger the mirror, the better they work. For example, building Webb’s large mirror meant finding a way to make a superb mirror that was 10 times lighter in weight per square meter than the already lightweight Hubble mirror. The engineers found a solution that was technically sweet but financially costly.

Similarly, the size of the rocket’s body matters because to fit Webb’s 21-foot-diameter mirror (6.5 meters) into the 13-foot-diameter body (4 meters) of its ride, the Ariane V rocket, it had to fold up like origami for launch. Normally, space missions try to avoid any moving parts, but for Webb they had no choice.

Again, the result was a technical triumph, but the complexity introduced over 300 places where one mistake could have ended the mission. Each one of the over 300 locations had to be 300 times less likely to fail than if there had been only one, pumping up the design, manufacturing and testing requirements – and inflating the cost.

The larger, wider Starship and New Glenn rockets mean that building a Webb-like space telescope today could be done with none of the origami-like folding and unfolding, with their attendant risks, and so be much cheaper.

New ideas

This opportunity is being seized by at least three teams. First, a proposed deep infrared telescope called Origins would take advantage of superheavy lift. Scientists at Caltech are studying a potential smaller version called Prima.

Second, an X-ray telescope that can take pictures as sharp as Webb – with a sensitivity to match – would likely use thicker and heavier mirrors than imagined just a few years ago.

And third, a study published in 2025 proposes a very low-frequency radio telescope, GO-LoW, that also takes advantage of using more mass. GO-LoW would be made of 100,000 tiny telescopes, so mass production savings kick in too.

All three of these telescopes would be easily 100 times more sensitive than their predecessors and at least comparable to Webb in their own bands of the spectrum.

It would be ideal if engineers could get these telescopes down to half the cost of a large observatory like Webb. Then, for the same price, NASA could fly two new Great Observatories instead of resigning itself to building one. If it could get the cost down to a third, it could potentially fly a full spectrum-spanning set.

Big challenges, big payoff

Of course, a lot could go wrong. For one thing, these rockets may not perform as advertised, either in capability or cost. Still, investing in a few starting studies won’t cost much and will likely have a big payoff.

For another, like the poet Goethe on his deathbed, we astronomers will always be asking for “more light.” But if we call for yet bigger and more complex telescopes than the already awesome Great Observatories recommended by the National Academies 2020 Astronomy Survey, then we will bring back all the costly issues faced by the Webb designers.

Space agencies have the challenge of keeping the astronomers’ endless desires under strict control – building to cost must come first.

But if agencies can keep astronomers’ ambitions from becoming too astronomical, while taking full advantage of the new design space opened up by the superheavy-lift rockets, then our understanding of the universe could advance beyond imagination in just a decade or so.

Martin Elvis does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organization that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

Read These Next

Will AI accelerate or undermine the way humans have always innovated?

An anthropologist’s new book lays out the formula for human innovation, from stone tools to supercomputers.…

How natural hydrogen, hiding deep in the Earth, could serve as a new energy source

Hydrogen demand around the world is projected to grow significantly by 2050. Some of that supply could…

AI’s growing appetite for power is putting Pennsylvania’s aging electricity grid to the test

As AI data centers are added to Pennsylvania’s existing infrastructure, they bring the promise of…