New materials, old physics – the science behind how your winter jacket keeps you warm

Winter jackets may seem simple, but sophisticated engineering allows them to keep body heat locked in, while staying breathable enough to let out sweat.

As the weather grows cold this winter, you may be one of the many Americans pulling their winter jackets out of the closet. Not only can this extra layer keep you warm on a chilly day, but modern winter jackets are also a testament to centuries-old physics and cutting-edge materials science.

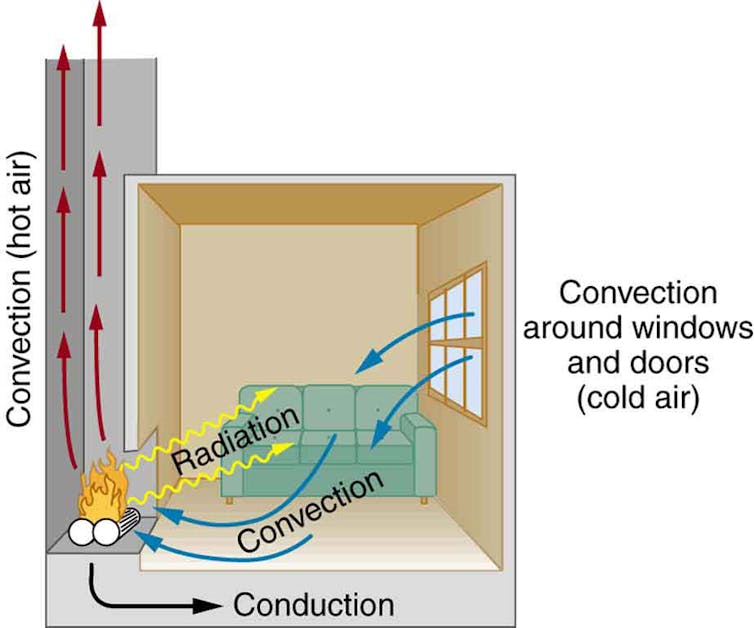

Winter jackets keep you warm by managing heat through the three classical modes of heat transfer – conduction, convection and radiation – all while remaining breathable so sweat can escape.

The physics has been around for centuries, yet modern material innovations represent a leap forward that let those principles shine.

Old science with a new glow

Physicists like us who study heat transfer sometimes see thermal science as “settled.” Isaac Newton first described convective cooling, the heat loss driven by fluid motion that sweeps thermal energy away from a surface, in the early 18th century. Joseph Fourier’s 1822 analytical theory of heat then put conduction – the transfer of thermal energy through direct physical contact – on mathematical footing.

Late-19th-century work by Josef Stefan and Ludwig Boltzmann, followed by the work of Max Planck at the dawn of the 20th century, made thermal radiation – the transfer of heat through electromagnetic waves – a pillar of modern physics.

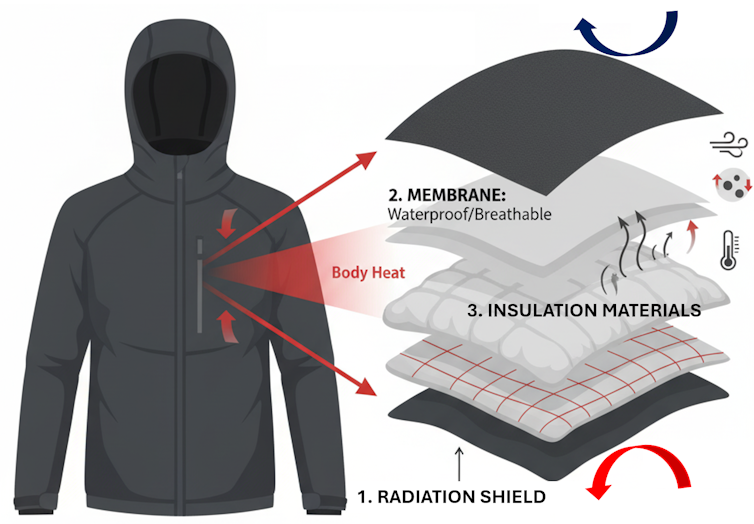

All these principles inform modern materials design. Yet what feels new today are not the equations but the textiles. Over the last two decades, engineers have developed extremely thin synthetic fibers that trap heat more efficiently and treatments that make natural down repel water instead of soaking it up. They’ve designed breathable membranes full of tiny pores that let sweat escape, thin reflective layers that bounce your body heat back toward you, coatings that store and release heat as the temperature changes, and ultralight materials.

Together, these innovations give designers far more control over warmth, breathability and comfort than ever before. That’s why jackets now feel warmer, lighter and drier than anything Newton or Fourier could have imagined.

Trap still air, slow the leak

Conduction is the direct flow of heat from your warm body into your colder surroundings. In winter, all that heat escaping your body makes you feel cold. Insulation fights conduction by trapping air in a web of tiny pockets, slowing the heat’s escape. It keeps the air still and lengthens the path heat must take to get out.

High-loft down makes up the expansive, fluffy clusters of feathers that create the volume inside a puffer jacket. Combined with modern synthetic fibers, the down immobilizes warm air and slows its escape. New types of fabrics infused with highly porous, ultralight materials called aerogels pack even more insulation into surprisingly slim layers.

Tame the wind, protect the boundary layer

A good winter jacket also needs to withstand wind, which can strip away the thin boundary layer of warm air that naturally forms around you. A jacket with a good outer shell blocks the wind’s pumping action with tightly woven fabric that keeps heat in. Some jackets also have an outer layer of lamination that keeps water and cold air out, and a woven pattern that seals any paths heat might leak through around the cuffs, hems, flaps and collars.

The outer membrane layer on many jacket shells is both waterproof and breathable. It stops rain and snow from getting in, and it also lets your sweat escape as water vapor. This feature is key because insulation, such as down, stops working if it gets wet. It loses its fluff and can’t trap air, meaning you cool quickly.

These shells also block wind, which protects the bubble of warm air your body creates. By stopping wind and water, the shell creates a calm, dry space for the insulation to do its job and keep you warm.

New tricks to reflect infrared heat

Even in still air, your body sheds heat by emitting invisible waves of heat energy. Modern jackets address this by using new types of cloth and technology that make the jacket’s inner surface reflect your body’s heat back toward you. This type of surface has a subtle space blanket effect that adds noticeable warmth without adding any bulk.

However, how jacket manufacturers apply that reflective material matters. Coating the entire material in metallic film would reflect lots of heat, but it wouldn’t allow sweat to escape, and you might overheat.

Some liners use a micro-dot pattern: The reflective dots bounce heat back while the gaps between them keep the material breathable and allow sweat to escape.

Another approach moves this technology to the outside of the garment. Some designs add a pattern of reflective material to the outer shell to keep heat from radiating out into the cold air.

When those exterior dots are a dark color, they can also absorb a touch of warmth from the sun. This effect is similar to window coatings that keep heat inside while taking advantage of sunlight to add more heat.

Warmth only matters if you stay dry. Sweat that can’t escape wets a jacket’s layer of insulation and accelerates heat loss. That’s why the best winter systems combine moisture-wicking inner fabrics with venting options and membranes whose pores let water vapor escape while keeping liquid water out.

What’s coming

Describing where heat travels throughout textiles remains challenging because, unlike light or electricity, heat diffuses through nearly everything. But new types of unique materials and surfaces with ultra-fine patterns are allowing scientists to better control how heat travels throughout textiles.

Managing warmth in clothing is part of a broader heat-management challenge in engineering that spans microchips, data centers, spacecraft and life-support systems. There’s still no universal winter jacket for all conditions; most garments are passive, meaning they don’t adapt to their environment. We dress for the day we think we’ll face.

But some engineering researchers are working on environmentally adaptive textiles. Imagine fabrics that open microscopic vents as the humidity rises, then close them again in dry, bitter air. Picture linings that reflect more heat under blazing sun and less in the dark. Or loft that puffs up when you’re outside in the cold and relaxes when you step indoors. It’s like a science fiction costume made practical: Clothing that senses, decides and subtly reconfigures itself without you ever touching a zipper.

Today’s jackets don’t need a new law of thermodynamics to work – they couple basic physics with the use of precisely engineered materials and thermal fabrics specifically made to keep heat locked in. That marriage is why today’s winter wear feels like a leap forward.

The authors do not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organization that would benefit from this article, and have disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

Read These Next

‘Hamnet’ is making audiences break down in tears – and upending beliefs about male grief

The Oscar-nominated film about Shakespeare’s son explores how men and women mourn differently –…

Federal benefits cuts are looming – here’s how Colorado is trying to protect families with children

A combination of Colorado state tax credits for low-income families is predicted to lift more than 50,000…

We study pandemics, and the resurgence of measles is a grim sign of what’s coming

Controlling the spread of many infections, including measles, depends on trust in public health, which…