With wolves absent from most of eastern North America, can coyotes replace them?

Wolves and coyotes feed on similar things – but their diets aren’t identical. A researcher studied predator diets to investigate their differences.

Imagine a healthy forest, home to a variety of species: Birds are flitting between tree branches, salamanders are sliding through leaf litter, and wolves are tracking the scent of deer through the understory. Each of these animals has a role in the forest, and most ecologists would argue that losing any one of these species would be bad for the ecosystem as a whole.

Unfortunately – whether due to habitat loss, overhunting or introduced species – humans have made some species disappear. At the same time, other species have adapted to us and spread more widely.

As an ecologist, I’m curious about what these changes mean for ecosystems – can these newly arrived species functionally replace the species that used to be there? I studied this process in eastern North America, where some top predators have disappeared and a new predator has arrived.

A primer on predators

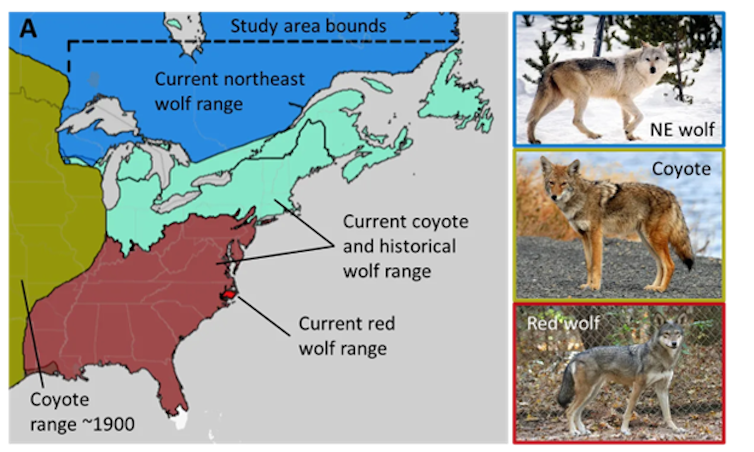

Wolves used to roam across every state east of the Mississippi River. But as the land was developed, many people viewed wolves as threats and wiped most of them out. These days, a mix of gray wolves and eastern wolves persist in Canada and around the Great Lakes, which I collectively refer to as northeastern wolves. There’s also a small population of red wolves – a distinct and smaller species of wolf – on the coast of North Carolina.

The disappearance of wolves may have given coyotes the opportunity they needed. Starting around 1900, coyotes began expanding their range east and have now colonized nearly all of eastern North America.

So are coyotes the new wolf? Can they fill the same ecological role that wolves used to? These are the questions I set out to answer in my paper published in August 2025 in the Stacks Journal. I focused on their role as predators – what they eat and how often they kill big herbivores, such as deer and moose.

What’s on the menu?

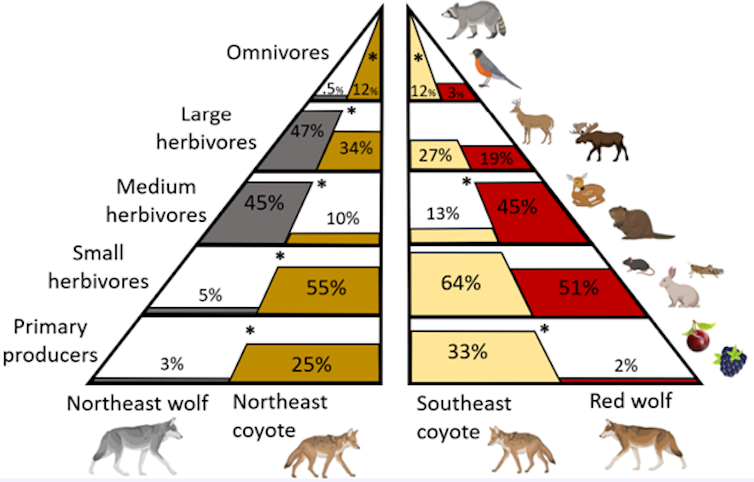

I started by reviewing every paper I could find on wolf or coyote diets, recording what percent of scat or stomach samples contained common food items such as deer, rabbits, small rodents or fruit. I compared northeastern wolf diets to northeastern coyote diets and red wolf diets to southeastern coyote diets.

I found two striking differences between wolf and coyote diets. First, wolves ate more medium-sized herbivores. In particular, they ate more beavers in the northeast and more nutria in the southeast. Both of these species are large aquatic rodents that influence ecosystems – beaver dam building changes how water moves, sometimes undesirably for land owners, while nutria are non-native and damaging to wetlands.

Second, wolves have narrower diets overall. They eat less fruit and fewer omnivores such as birds, raccoons and foxes, compared to coyotes. This means that coyotes are likely performing some ecological roles that wolves never did, such as dispersing fruit seeds in their poop and suppressing populations of smaller predators.

Killing deer and moose

But diet studies alone cannot tell the whole story – it’s usually impossible to tell whether coyotes killed or scavenged the deer they ate, for example. So I also reviewed every study I could find on ungulate mortality – these are studies that tag deer or moose, track their survival, and attribute a cause of death if they die.

These studies revealed other important differences between wolves and coyotes. For example, wolves were responsible for a substantial percentage of moose deaths – 19% of adults and 40% of calves – while none of the studies documented coyotes killing moose. This means that all, or nearly all, of moose in coyote diets is scavenged.

Coyotes are adept predators of deer, however. In the northeast, they killed more white-tailed deer fawns than wolves did, 28% compared to 15%, and a similar percentage of adult deer, 18% compared to 22%. In the southeast, coyotes killed 40% of fawns but only 6% of adults.

Rarely killing adult deer in the southeast could have implications for other members of the ecological community. For example, after killing an adult ungulate, many large predators leave some of the carcass behind, which can be an important source of food for scavengers. Although there is no data on how often red wolves kill adult deer, it is likely that coyotes are not supplying food to scavengers to the same extent that red wolves do.

Are coyotes the new wolves?

So what does this all mean? It means that although coyotes eat some of the same foods, they cannot fully replace wolves. Differences between wolves and coyotes were particularly pronounced in the northeast, where coyotes rarely killed moose or beavers. Coyotes in the southeast were more similar to red wolves, but coyotes likely killed fewer nutria and adult deer.

The return of wolves could be a natural solution for regions where wildlife managers desire a reduction in moose, beaver, nutria or deer populations.

Yet even with the aid of reintroductions, wolves will likely never fully recover their former range in eastern North America – there are too many people. Coyotes, on the other hand, do quite well around people. So even if wolves never fully recover, at least coyotes will be in those places partially filling the role that wolves once had.

Indeed, humans have changed the world so much that it may be impossible to return to the way things were before people substantially changed the planet. While some restoration will certainly be possible, researchers can continue to evaluate the extent to which new species can functionally replace missing species.

Alex Jensen does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organization that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

Read These Next

How the Emerald Isle shaped the Steel City – Pittsburgh’s rich Irish history

Long before Pittsburgh’s modern Irish celebrations existed, Irish immigrants helped shape the city…

As the Oscars approach, Hollywood grapples with AI’s growing influence on filmmaking

AI tools can now generate movie scenes, resurrect lost footage and replace entry-level jobs – forcing…

When US fights in the Middle East, American Muslim students often face discrimination

The war on terror is among the Middle East conflicts that sparked a rise of anti-Muslim and anti-Arab…