Research breakthroughs often come through collaborations − attacks on academic freedom threaten this

Academic freedom grew strongly after World War II, with greater university funding, protections and autonomy, yet global data now shows a decline.

Since President Donald Trump took office for the second time, many researchers across academic disciplines have had their funding cut because of their purported ideological bias. These funding cuts were further exacerbated by the extensive 2025 government shutdown.

As a team of sociologists studying universities, higher education policy and administration, academic freedom and science production, we recognized these cuts as part of a recent global trend of weakened academic freedom. Since the mid-2000s, political attacks on higher education have increased in many countries. Consequently, academic freedom has declined in countries as different as India, Israel, Nicaragua and the United Kingdom, among others.

For example, for years Hungarian Prime Minister Viktor Orbán accused the internationally respected Central European University of “liberal bias.” By 2019, he had effectively forced the university and its faculty into exile in Vienna, Austria. Since Argentinian President Javier Milei came to power in 2023, he has made repeated claims that academics are corrupt elites. He used this narrative to restrict universities’ autonomy and funding of their research programs.

Today, most research is done collaboratively. But research finds that when individual scholars have less academic freedom and universities’ autonomy declines, global research collaborations are also threatened.

The prevalence and complexity of those collaborations that optimize human and material resources has grown, with substantial impact on scientific productivity — what we call the global “collaboration dividend.” Collaborations foster solutions to complex problems, from vaccine development to renewable energy. Diminishing academic freedom erodes these collaboration dividends, which then reduces the quantity and quality of scientific discovery worldwide.

The United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization recommendation concerning the status of higher education teaching personnel builds on Article 26 of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights and urges governments to protect academics from political surveillance and interference on two levels.

First, UNESCO affirms the right of individual faculty to teach, research, share findings and express their expert opinions independently. Second, UNESCO recognizes the right of universities to autonomously make decisions about facilitating research, hiring and promoting faculty, and developing curricula without state interference.

Academic freedom and global collaborations

Data from the Varieties of Democracy, or V-DEM, project demonstrate international trends in academic freedom. V-DEM is a large, widely used international dataset based on experts evaluating political developments. It tracks infringements and protections of these rights in every country over the past hundred years. The index we used measures dimensions of academic freedom.

Suppressed in the 1930s by global economic depression, rising fascism and military conflict, academic freedom reached a low point during World War II. It then rebounded and grew strongly.

More countries began recognizing the benefits of free inquiry and guaranteed independent science, especially from 1980 to the mid-2000s. Nations everywhere expanded the capacity of their universities to undertake scientific research and collaborate across boundaries. A new global model of the research university fostered the exponential growth of scientific knowledge.

Also, in part as a defense against totalitarianism, many countries signed on to international agreements upholding academic freedom, such as the International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights. This agreement declares that the basic human right to an education “can only be enjoyed if accompanied by the academic freedom of staff and students.”

The strengthening of academic freedom paralleled the largest historical expansion of the world’s capacity to undertake research on science, technology, engineering, mathematics and medicine, or STEMM. But over the past decade, freedoms of faculty members and universities began to weaken in many countries, including in the United States.

Today, university-based scientists co-author 85% to 90% of the several million STEMM research papers produced annually. Large, complex collaborations are increasingly a driving force in discovery. The global expansion of academic freedom enables universities and their scientists to participate in this intensifying collaboration dividend through joint research with colleagues elsewhere.

In studies published between 2024 and 2025, we presented troubling trends about declining academic freedom, collaborations and scientific research at universities in countries across the world.

First, we analyzed individual academic freedom and STEMM production in 17 research productive countries from 1981 to 2007. We found that academic freedom protections raise the quantity and quality of research, while infringements on these safeguards lower them.

Second, we found that safeguarding universities’ organizational autonomy also increases the volume and excellence of a country’s STEMM research output. Both associations are independent of other influential factors behind countries’ scientific productivity, such as governmental research spending, a country’s wealth or university enrollments.

Third, a related study by others finds that restricting academic freedom reduces scientists’ and universities’ ability to effectively participate in international research collaborations.

Diminishing the collaboration dividend

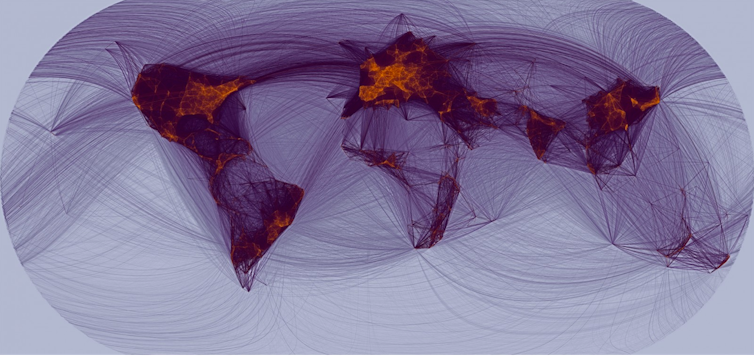

Together, these findings underscore that academic freedom allows researchers to participate in complex collaborations, which in turn increases research production. Most of these collaborations aren’t just facilitated by individual scientists, however. Global collaborations are made up of networks of universities, and declining academic freedom can threaten the ties between these institutions and their scientists’ projects.

The popular image of the solitary genius making isolated breakthroughs is largely a myth. Research teams have steadily increased in size, and “super-collaborative” groups of hundreds or even thousands of scientists now work together on complex projects. Together, they produce ever greater amounts of knowledge. Because individual researchers’ output is fairly steady over their careers, real productivity gains in science now depend on global collaboration and shared resources. This is true even as the number of scientists grows.

In the early 1980s, three geographical superhubs of robust, primarily university-based collaborative research emerged. One is Europe, another is North America. The third, East Asia, is growing rapidly.

By 1980, universities in the European and North American hubs collaborated on publications with scientists in 100 other countries. This number grew to 193 countries by 2010. Currently, over a fourth of the millions of annual STEMM papers are the result of international collaborations. This process is heavily dependent on universities and their freedom to pursue science.

Moreover, superhubs can accelerate international collaboration for scientists in other countries not originally in these hubs. Such collaborations enable their universities to leapfrog into new superhub status. South Korean universities have been an example of this process over the past several decades.

This collaborative capacity has enabled the production of millions of co-authored papers and scientific advances. For instance, these collaborations allowed for the rapid development of COVID-19 vaccines.

Collaborative networks depend on university support, not just individual scientists. This is why our research suggests declining academic freedom at the university level makes them vulnerable. A troubling three-quarters of U.S.-based scientists have considered leaving the country in response to threats against academic freedom in the U.S. since early 2025.

This research suggests that at stake here is not only the freedom of scholars and academic institutions, but also the future of discovery itself. Academic freedom is essential for scientists around the world to collaborate, enabling the scientific discoveries necessary for technological innovation, medical breakthroughs, and social and environmental problem-solving.

Volha Chykina has received funding from Mellon Foundation / Scholars at Risk to support her research on academic freedom.

David P. Baker has received funding for research on higher education and science from Luxembourg's FNR, and Qatar's QNRF

Frank Fernandez has received funding from Mellon Foundation/Scholars at Risk to support his research on academic freedom.

Justin Powell has received funding for research on higher education and science from Germany's BMBF, DFG, and VolkswagenStiftung; Qatar's QNRF; and Luxembourg's FNR.

Read These Next

Tiny recording backpacks reveal bats’ surprising hunting strategy

By listening in on their nightly hunts, scientists discovered that small, fringe-lipped bats are unexpectedly…

Bad Bunny says reggaeton is Puerto Rican, but it was born in Panama

Emerging from a swirl of sonic influences, reggaeton began as Panamanian protest music long before Puerto…

Minneapolis united when federal immigration operations surged – reflecting a long tradition of mutua

Minnesotans from all walks of life, including suburban moms, veterans and protest novices, have bucked …