Mountain chickadee chatter: Scientists are decoding the songbird’s complex calls

Mountain chickadees follow systematic grammarlike rules to share important information, stringing together syllables like words in a sentence.

I approach a flock of mountain chickadees feasting on pine nuts. A cacophony of sounds, coming from the many different bird species that rely on the Sierra Nevada’s diverse pine cone crop, fill the crisp mountain air.

The strong “chick-a-dee” call sticks out among the bird vocalizations. The chickadees are communicating to each other about food sources – and my approach.

Mountain chickadees are a member of the family Paridae, which is known for its complex vocal communication systems and cognitive abilities. Along with my advisers, behavioral ecologists Vladimir Pravosudov and Carrie Branch, I’m studying mountain chickadees at our study site in Sagehen Experimental Forest, outside of Truckee, California, for my doctoral research. I am focusing on how these birds convey a variety of information with their calls.

The chilly autumn air on top of the mountain reminds me that it will soon be winter. It is time for the mountain chickadees to leave the socially monogamous partnerships they had while raising their chicks to form larger flocks. Forming social groups is not always simple; young chickadees are joining new flocks, and social dynamics need to be established before the winter storms arrive.

I can hear them working this out vocally. There’s an unusual variety of complex calls, with melodic “gargle calls” at the forefront, coming from individuals announcing their dominance over other flock members.

Examining and decoding bird calls is becoming an increasingly popular field of study, as scientists like me are discovering that many birds – including mountain chickadees – follow systematic rules to share important information, stringing together syllables like words in a sentence.

Songs vs. calls

For social animals, communication is a crucial part of everyday life. Communication can come in the form of visual, chemical, tactile, electrical or vocal signals.

Birds are highly vocal, often relying on vocal communication to effectively interact with their environments and flock members. Temperate songbirds, including cardinals, bluebirds, wrens and blackbirds, have two main categories of vocalizations: songs and calls.

Songs are vocalizations that are used primarily in the spring, during breeding season. Males in temperate regions sing to attract females and defend territories.

Calls are basically any vocalization that is not a song. This category includes a limitless variety of vocalizations that communicate all sorts of essential information.

Most songbird species have complex songs and fairly simple calls. This is why vocalizations sound most melodic during the spring, when birds are attracting mates and breeding.

However, chickadees are unusual in that they sing very simple songs relative to the complexity of their calls. Research suggests this is largely due to their social structure and complex environments. Living in flocks for the majority of the year means they need an elaborate communication system year-round. This is in contrast to many other songbird species that are more solitary during the nonbreeding season.

Scientists know quite a lot about birdsong: It is highly organized and composed of multiple units that are strung together into “phrases,” like how musical notes are strung together in a song.

Some species manipulate their song to sound more impressive, by incorporating new elements or performing impressive acoustic feats through note modification – imagine a trill or an impressive high note.

Some songbirds must learn their songs from their parents and other adult males during a sensitive period in the first several months of their lives. It’s similar to how human children must learn how to speak from adults during a similar early sensitive period.

In contrast, we know relatively little about the structure and organization of complex calls. Scientists have often regarded calls as unexciting and simple compared with birdsong. However, calls are arguably the most important type of vocalization, at least for highly social bird species.

Translating mountain chickadee calls

I spend my days out at our field site in the beautiful Sierra Nevada, following and recording chickadees as they communicate with each other. I have taken numerous focal recordings, where I stand in the forest with a directional microphone, identifying vocalizations and behaviors in real time.

I also have hundreds of hours of recordings taken by automated recording devices called AudioMoths. These allow me to record vocalizations in the absence of people.

The extensive vocal repertoire of mountain chickadees has yet to be fully documented. There are five basic categories of call types:

- Contact calls: communicate identity, sort of like a name, and location.

- “Chick-a-dee” calls: coordinate flock movement and communicate a variety of complex information about the environment, from food availability to predator presence and type.

- Alarm calls: alert others of the presence of a predator.

- Begging calls: used by chicks or females to elicit feeding behavior from males.

- Gargle calls: advertise dominance over other individuals in a flock, primarily used by males.

“Chick-a-dee” calls contain several elements resembling the basic elements of human grammar. Essentially, the various sounds a chickadee utters mean different things, similar to words in human languages. And the way that a chickadee combines these sounds changes the meaning. Word order matters, just like grammar matters in human language. If a chickadee were to phrase its calls in the wrong note order, the call would no longer convey the same meaning, even if composed of the same elements.

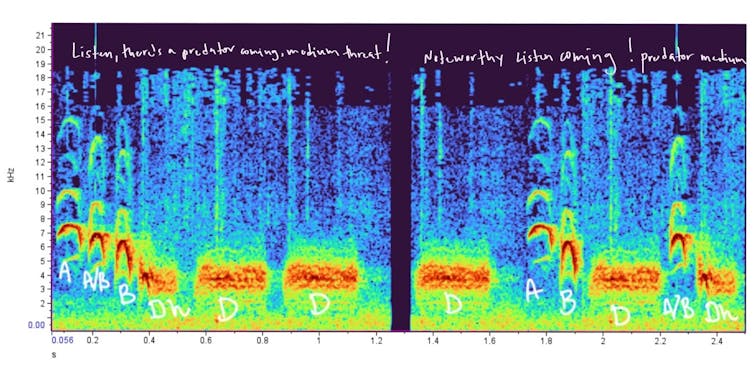

The “chick-a-dee” call of the mountain chickadee contains six elements, known as notes or syllables, that can be combined in hundreds of unique combinations to say many different things. These elements are labeled A, A/B, B, C, D and Dh.

Although scientists don’t fully know the meaning of each note in different contexts, it is generally believed that A notes typically contain identifying information about how important the topic seems to the caller, while A/B and B notes tend to further inform the listener of the topic of conversation. C notes contain information about the subject of the call, often a food source, and D notes convey information about the excitement and urgency of the message, including level of threat of a spotted predator or size of a food source. The D notes basically function like exclamation points at the end of a sentence, while the other notes convey more specific information.

Mountain chickadees can use their “chick-a-dee” calls to convey hundreds of different phrases that are relevant to navigating their habitats and social environments. As a hypothetical example, a mountain chickadee call might have the following syntax: A-A-A/B-B-D-D, which could roughly translate to something like, “Listen to me carefully (A-A): there is a predator (A/B) close by (B) and a medium threat level (DD).”

If the note order switched to D-A-B-D-A/B-A, the sentence would look more like: “Noteworthy listen close by noteworthy predator listen to me.” Although all the same elements are there, this sentence is now much more difficult to comprehend. Notes that are out of order can confuse chickadees, preventing them from grasping the correct meaning of the call.

This “translation” is an example based on what we have learned from playback experiments, but the exact meaning will depend on the specific population and surrounding environment.

Analyzing the ‘chick-a-dee’ calls

Back in the lab, I parse through the endless hours of recordings using a deep-learning algorithm that I have modified to identify the specific calls of our chickadee population.

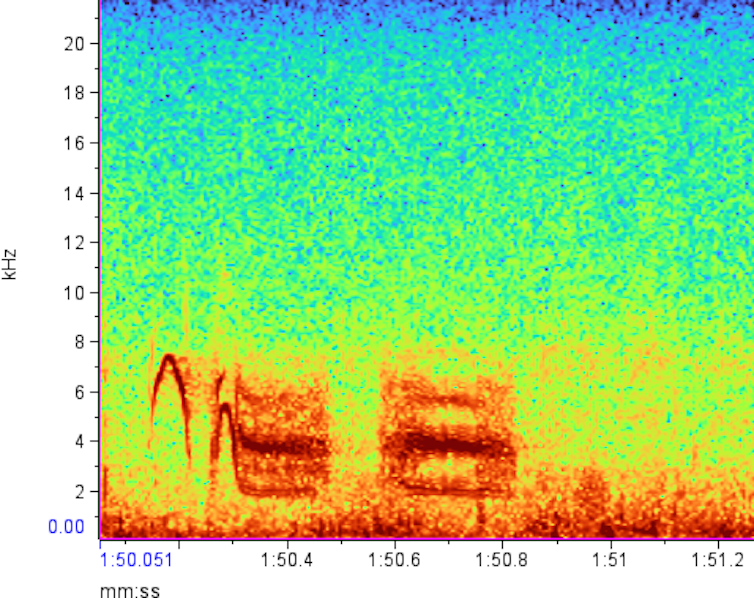

I then use Raven Pro software, developed by the Cornell Lab of Ornithology, to visually inspect and analyze these calls on a spectrogram: a visual representation of sound, with frequency on the vertical axis, and time on the horizontal axis. This visualization allows me to study the structure of calls in great detail.

Studying spectrograms can get me only so far. The next step is to experimentally test different “chick-a-dee” calls out in the wild. Using audio editing software, I manipulate the syntax of calls to either follow grammatical rules or violate them. Then, I broadcast these manipulated recordings out in the forest and observe how our chickadees react to grammatically incorrect calls, which would sound like gibberish to them.

My hope is that this combination of experimental testing of calls and careful visual analysis will provide a step toward understanding the subtle complexities of chickadee communication. I’m trying to home in on the meaning of different syllables and syntax, the grammatical rules.

Back in the forest with my directional microphone, watching the chickadees flit about, I hear different versions of the “chick-a-dee” calls. Some feature more D notes, which would indicate a higher level of excitement. Others feature more A, B or C notes, communicating more specific, identifying information. I am also surrounded by melodic gargle calls, harsh scolding calls and barely audible soft calls.

Next time you find yourself out in the forest, stop and listen to the chickadees as they talk to each other. Maybe you’ll be able to hear the variation in their calls and know that they are talking about different things − and that grammar matters.

Sofia Marie Haley does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organization that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

Read These Next

Held captive in their own country during World War II, Japanese Americans used nature to cope with t

Incarcerated in rough barracks surrounded by barbed wire and armed soldiers, Japanese Americans made…

Valentine’s Day cards too sugary sweet for you? Return to the 19th-century custom of the spicy ‘vine

Victorians found a way to anonymously tell people they didn’t like exactly how they felt.

Philadelphia was once a sweet spot for chocolatiers and other candymakers who made iconic treats for

Goldenberg’s Peanut Chews, Goobers and Whitman’s Sampler boxes of chocolates are just a few confectionary…