Placenta bandages have far more health benefits than risky placenta pills − a bioengineer explains

Placentas contain a rich amount of nutrients and stem cells, but there’s a difference between eating it at home for wellness and using it in the clinic to improve wound healing.

Eating a placenta may not give you the health benefits some people want you to believe it has, but using it as a bandage might.

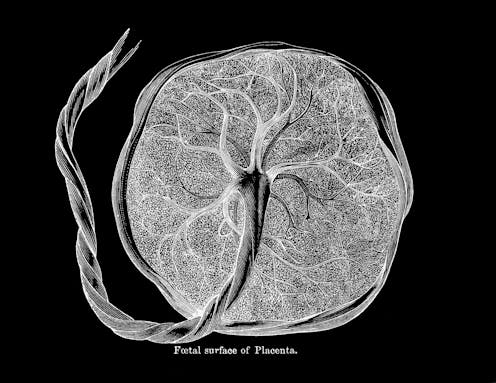

The placenta is an organ created during pregnancy that provides nutrients to a growing fetus through an umbilical cord. It’s usually large and relatively flat, composed of blood vessels, stem and immune cells, and collagen. It doesn’t look particularly appetizing to most people, and those who have eaten placentas often mention an unpleasant taste or smell.

But in the early 2000s, the practice of mothers eating their placenta after childbirth, claiming health benefits and mood improvement, gained mainstream attention. This trend typically involves putting your placenta into capsules you can take as pills, and there are even companies selling custom-made and do-it-yourself products online.

While some mammals may eat their own placentas due to limited nutritional resources in the wild, the benefits people might get from eating placentas is unclear.

If boiled and dehydrated, the useful components of the placenta may be altered and reduced. If ingested raw, pathogens may remain on the surface of the placenta. In 2016, after a newborn was hospitalized multiple times from an infection potentially resulting from the mother ingesting her placenta, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention recommended mothers avoid taking placenta pills.

I can’t personally speak to the taste of placentas. However, as a bioengineer who designs materials to regenerate injured bones and other tissues, I along with my colleagues have uncovered a much clearer picture of the benefits placentas can offer as a biomaterial to repair wounds – if used properly.

Placenta as biomaterial

Biomaterials are materials designed to interface with your body to repair damage. If you burned your skin, for example, your doctor may use a biomaterial such as a skin graft to help your body repair the damaged tissue, ideally providing nutrients to the damaged area to promote cell growth.

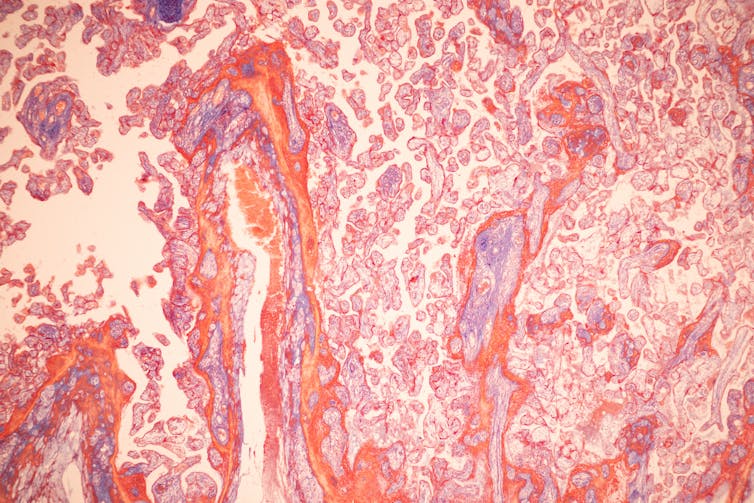

Researchers have been exploring recycling placentas, which are often thrown away after delivery, as a type of biomaterial to regrow wounded tissue in patients. Because the placenta is rich in nutrients and stem cells that give it antimicrobial, anti-inflammatory and pro-regenerative properties, this organ is a particularly good candidate for medical applications.

Your body normally responds to a wound with inflammation, which is an immune reaction that clears harmful stimuli and pathogens, often resulting in swelling and pain around the injury site.

Unfortunately, sometimes this inflammatory process can get out of hand and lead to chronic wounds and prevent healing. But the active biomolecules within the placenta work with your immune system to promote repair by reducing inflammation and preventing scar formation.

For example, chronic diabetic foot ulcers are a challenging injury that sometimes never closes and leads to foot amputation. Researchers found that using biomaterials made of parts of the placenta to treat these injuries resulted in a wound closure rate 6.24 times higher than conventional treatments. Researchers have also found that placenta-based biomaterials can reduce scarring after heart injury.

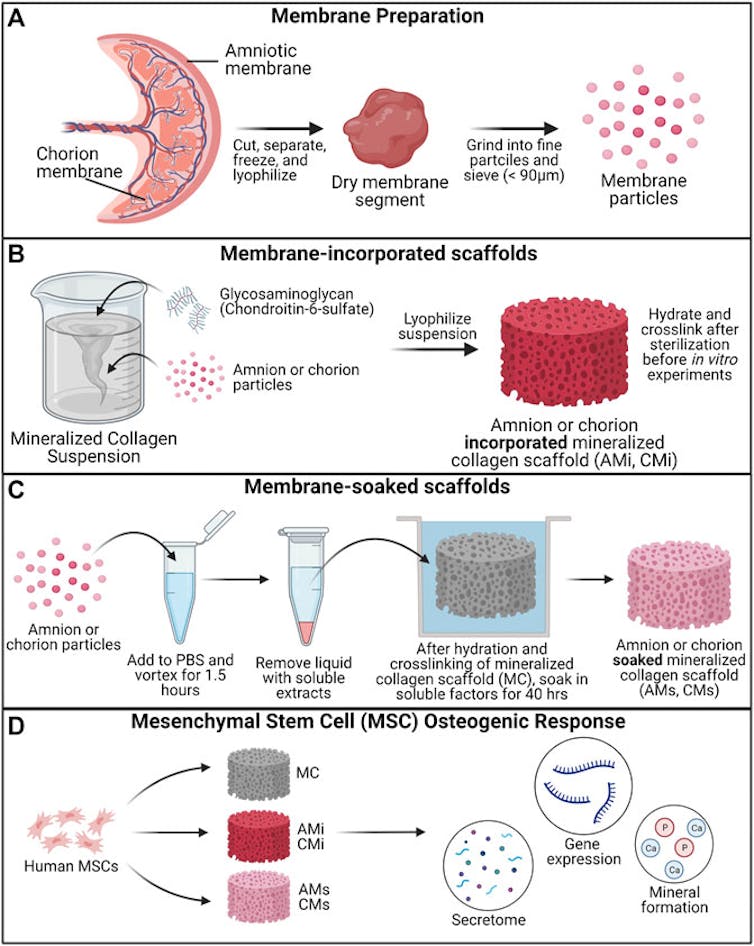

I have used human placentas in my own research to study how they work in a variety of wound repair scenarios. I can take a volunteer patient’s donated placenta and remove factors that may negatively affect healing, such as all cells, blood and other components that may cause inflammation. Then I can take the material that’s left – primarily containing essential growth nutrients and the tissue foundation that cells used to live in – and use it to improve bone or tendon repair.

Moreover, placentas contain stem cells that can also be useful for medicine. These cells are able to turn into various other types of cells of your body. This can be particularly helpful for repairing organs that are difficult to directly harvest cells from, such as the heart, liver and nerves. For example, placental stem cells can be added to an injured heart and become heart cells themselves to aid in repair.

Researchers have also used stem cells from the placenta and the umbilical cord for applications such as stem cell transplantation to treat disease and injury. Studies have found that placenta-derived stem cells transplanted into rats could reverse Parkinson’s and nerve death. Stem cells from the placenta can also serve as a more promising source of cells for cell transplantation therapies compared with stem cells from fat and bone marrow.

On your skin, not in your stomach

So placentas do have some clear health benefits. But why are they more useful as a biomaterial bandage than as a pill or food, taste considerations aside?

Unlike placenta products that are ingested – pills, dried jerky or raw placenta – biomaterials have undergone rigorous testing to ensure they are safe and effective. They are processed and handled in a controlled laboratory environment and often sterilized to ensure no bacteria or other pathogens can enter the patient. The Food and Drug Administration has approved several placenta-based biomaterials for use in the clinic, including to treat diabetic foot wounds, surgical wounds and tissue replacement.

In contrast, placentas and placenta products eaten at home may not receive proper treatment to kill the many harmful pathogens that may be present during transport. The processing to turn placentas into something ingestible may also damage their beneficial components, leading to increased health risks and reduced benefits. No ingested placenta products have received FDA approval to date.

Eating placentas won’t make you any healthier. But science says applying a lab-processed, placenta-based biomaterial to a recent wound might speed up healing and result in smoother, scar-free skin.

Marley Dewey receives funding from the National Science Foundation and the National Institutes of Health.

Read These Next

How do scientists hunt for dark matter? A physicist explains why the mysterious substance is so hard

Dark matter doesn’t seem to interact with the matter we can see and touch, so scientists look for…

Infusing asphalt with plastic could help roads last longer and resist cracking under heat

A research team has paved plastic-infused roads in Texas and Bangladesh, with promising results.

Americans are asking too much of their dogs

People don’t just love their dogs; Many owners seem to love pets more than people. It’s a symptom…