Meet phosphine, a gas commonly used for industrial fumigation that can damage your lungs, heart and

While scientists still aren’t sure how phosphine wreaks so much havoc on the body, some are developing medications that can help mitigate the harm it causes.

In 1980, two children and 29 crew members aboard a grain freighter became ill. They had been exposed to phosphine – a chemical used in fumigation to kill pests in and on grain – for four days. In the end, one child died.

More recently, in 2024, a family in the Dominican Republic was poisoned with phosphine gas after fumigation of an apartment in their building. The goal had been to eliminate a woodworm infestation, but building management hadn’t notified residents. Two of the family members died.

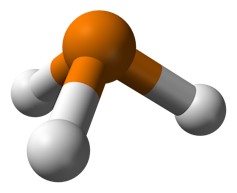

Researchers know that phosphine, also known as PH₃, is the highly toxic gas connected with all these deaths. So, are there ways to prevent more of these deaths moving forward?

As a pharmaceutical scientist, I study ways in which chemicals affect the human body. Currently, I am working to understand the mechanism by which phosphine harms people and developing therapies that counteract phosphine gas exposure.

One promising approach that my team is developing is a group of inhalable therapies that counteract the lung damage phosphine gas exposure can cause.

Phosphine industry use

Phosphine is widely used in a variety of industries.

The semiconductor industry uses phosphine as an agent in the production of materials. Phosphine is also used as a chemical that helps in the preparation of some flame retardants.

But most importantly, it’s used as an insecticide, rodenticide and fumigant – a pesticide that turns into a gas when applied – to control pests or harmful microorganisms. Phosphine kills insects by disrupting their breathing and metabolism.

Containers filled with bulk agricultural and forestry products – such as grains and wood – often undergo fumigation on ships to prevent insect infestations.

A toxic threat

Phosphine gas is colorless and odorless, though in its commercial grade form it can smell of garlic or rotten fish.

The U.S. National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health and the U.S. Occupational Safety and Health Administration have regulations stating that workers should not inhale more than 0.3 parts per million on average over an 8-hour work shift.

A phosphine concentration of 0.3 parts per million means that three out of every 10 million air molecules is phosphine. So, only a tiny amount of phosphine in the air can harm a worker’s health.

Phosphine gas exposure can cause symptoms including nausea, vomiting, abdominal pain, diarrhea, thirst, chest tightness, breathing difficulty, muscle pain, chills and pulmonary congestion. A severe exposure might damage your heart and even cause death.

These toxic effects can start to occur within the first few hours after you inhale phosphine. More severe symptoms, such as cardiovascular damage, can cause death within 12 to 24 hours after an exposure.

Phosphine can also damage the liver and kidneys, but it may take longer – two to three days – for these symptoms to show. Deaths that occur more than a day after exposure are usually related to liver or kidney failure.

Fluid in the lungs, called pulmonary edema, can also occur after exposure, usually around 72 hours later.

The exact number of deaths associated with phosphine gas exposure is unknown but believed to be increasing and significant.

One review of 26 phosphine poisoning deaths found that lung congestion was most commonly the final killer.

Phosphine exposure

Researchers still aren’t sure what exactly makes phosphine so toxic.

Some studies suggest that phosphine stresses the body by generating reactive oxygen species, a type of unstable molecule that easily reacts with other molecules in your body’s cells.

Too many of these reactive oxygen species can damage the DNA, RNA and proteins in your body’s cells, as well as their mitochondria, which generate cellular energy. Enough damage can kill the cells.

Right now, there is no antidote for phosphine poisoning available.

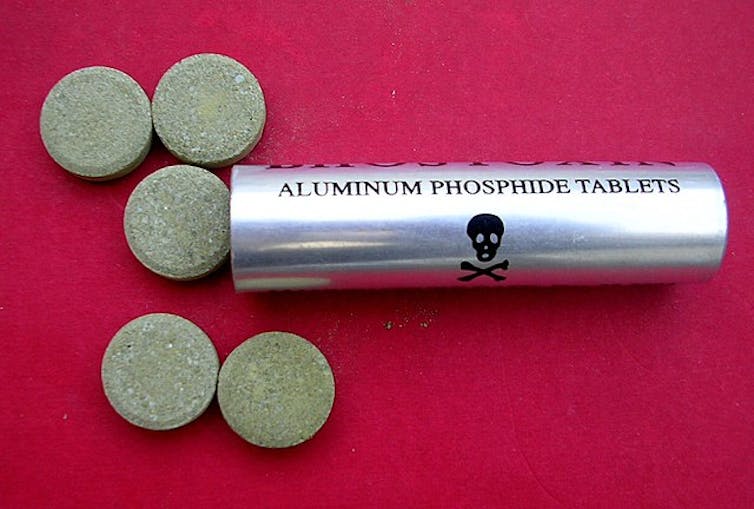

People who handle phosphine in the workplace, including those who work in storage facilities and cargo ships that use aluminum phosphide tablets for fumigation, can use respiratory equipment that meets federal regulatory standards for protection.

Hospitals can treat symptoms from phosphine gas exposure. Researchers, like those on my team, are studying other medications that may help reduce the severity of lung injury and help patients recover lung function.

These medications include inhalable therapies that could reduce lung damage and inflammation.

Phosphine is a useful and effective chemical when handled appropriately. But as with many other chemicals, those who use it should understand its risks, read labels before using it, store it in its original container in a secure place and dispose of it safely.

Aliasger K. Salem receives funding from the National Institutes of Health. He serves on the Executive Board of the American Association for Pharmaceutical Scientists.

Read These Next

ICE and Border Patrol in Minnesota − accused of violating 1st, 2nd, 4th and 10th amendment rights −

In Minnesota, can constitutional protections withstand the actions of a federal government seemingly…

Lüften sounds simple – but ‘house-burping’ is more complicated in Pittsburgh

A German habit has been trending in recent weeks: ‘lüften,’ or airing out your home. It can help…

‘Inoculation’ helps people spot political deepfakes, study finds

Priming people to watch out for political deepfakes helps them question the AI-generated videos.