Twins were the norm for our ancient primate ancestors − one baby at a time had evolutionary advantag

Twins are pretty rare, accounting for just 3% of births in the US these days. But new research shows that for primates 60 million years ago, giving birth to twins was the norm.

Twins have been rare in human history and for that reason can seem special. Many cultures associate twins with health and vitality, while others see them as a philosophical reminder of the duality of life and death, good and evil. Some famous twins are credited with the birth of nations, others are described as deities.

Our recent research suggests that twins were actually the norm much further back in primate evolution, rather than an unusual occurrence worthy of note. Despite the fact that almost all primates today, including people, usually give birth to just one baby, our most recent common ancestor, which roamed North America about 60 million years ago, likely gave birth to twins as the standard.

We have been researching the evolution of primate litter size – how many babies grow during each pregnancy – for the past several years. To study mammal evolution and reproductive life history, we use skeletal collections, both fossil and recently living.

In addition to being an anthropologist, one of us (Tesla) is the mother of twin girls. That’s led to a personal and not just scientific interest in this topic: When did twin pregnancies become uncommon?

Reconstructing litter size in the past

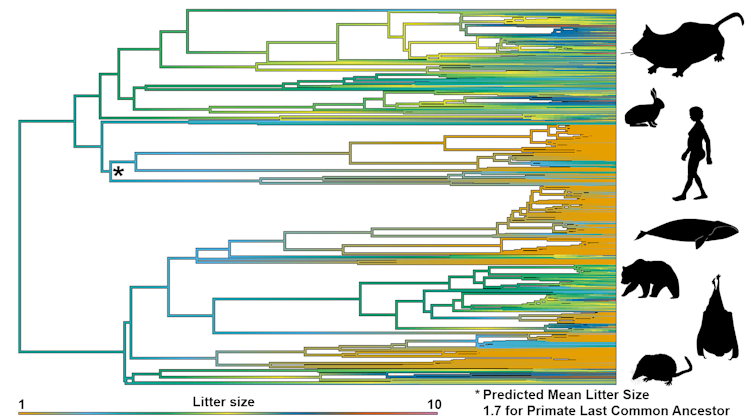

The best way we have to reconstruct the history of litter size is to map the known litter size of as many species as possible across the mammalian family tree and then use mathematical algorithms to look for patterns. But outside of rare events where entire animal families are fossilized together, it is extraordinarily difficult to assess litter size for extinct species from the skeleton alone. So we instead collect data on as many living mammals as possible.

We searched a wide variety of public databases, including AnAge: The Animal Ageing and Longevity Database, for information about how many offspring are commonly born to each species of mammal. We also noted additional data, including what the species’ average body size is at birth and at adulthood, as well as pregnancy duration.

After gathering all these data points for almost a thousand mammal species, we performed a series of statistical tests to quantify relationships between different traits. Our goal was to estimate the likely litter size of different mammalian ancestors: What were the odds of a singleton birth for each species at any given point in time?

The number of offspring a species has in a litter is phylogenetically conserved, meaning more similar in more closely related species. Deer tend to have one or two offspring, while canids and felids tend to have many more babies in each litter.

Almost all primate species give birth to just one baby, although there are exceptions. Tarsiers, several of the wet-nosed primates – including lemurs, lorises and galagos – and almost all of the marmosets and tamarins from South America give birth to twins.

Prior to our work, researchers thought these distinctive twin-bearing primates must be what evolutionary biologists call derived, or different, from the more common, ancestral trait. But our research flips that narrative on its head: It’s actually the singleton-bearing primates that are derived and distinctive. Further back in evolution, two babies at once was the norm. Our ancient primate ancestors gave birth to twins.

So, when did this evolutionary change in primate litter size occur?

The switch to singletons

Modern humans overwhelmingly birth just a single child – a rather large child with an even larger head. Human brain and body size is certainly connected to our ability to create and refine technologies. Paleoanthropologists have long been investigating what they call encephalization: an increase in brain size relative to body size over evolutionary time.

For primates, and especially humans, childhood learning is crucial. We propose that the switch from twins to singletons was critical for the evolution of large human babies with large brains that were capable of complex learning as infants and young children.

Based on mathematical modeling, the switch to singletons occurred early on, at least 50 million years ago. From there, many primate lineages, including ours, evolved to have increasingly larger bodies and brains.

Our new research also shows that the switch from birthing twins to birthing singletons happened multiple times in the primate lineage – a telltale signal that it was advantageous for primates to develop only one fetus per pregnancy. Because multifetal gestation requires more energy from the mother, and because the babies are born smaller, and often earlier, early primate ancestors who gave birth to just one large offspring may have been at a survival advantage.

Our findings don’t mean that having twins today is a disadvantage – although, as a mother of multiples, Tesla can certainly say it’s not easy. But having twins today is quite a different experience from our tiny primate ancestors birthing in the trees 60 million years ago.

Twinning today

Rates of twins have almost doubled in the U.S. over the past 50 years, due in part to advances in assistive reproductive technologies. Today, about 3% of live births are twins, although recent trends suggest a downturn in rates. The fact that women in the U.S. are routinely having kids in their 30s compounds this even further, since women in the later stages of fertility – that’s anyone over the age of 35 – are more likely to have twins.

But having twins can be dangerous for both the mother and babies. More than half of all twins in the U.S. are born prematurely. Many of them spend time in the neonatal intensive care unit.

Despite these risks, our research shows that twins are a critical part of our genetic history.

Tesla Monson receives funding from the Leakey Foundation, the National Science Foundation, and Western Washington University.

Jack McBride has previously received funding from Western Washington University, he is currently affiliated with Yale University.

Read These Next

Why are so many statues naked? An art historian explains this tradition’s ancient roots

Nudity can express everything from innocence to sexual desire, from triumph to defeat.

There aren’t enough geriatricians – here’s how older adults can still get the right care

A few simple strategies can help older adults convey their needs to their health care provider.

Will AI accelerate or undermine the way humans have always innovated?

An anthropologist’s new book lays out the formula for human innovation, from stone tools to supercomputers.…