Is it really hotter now than any time in 100,000 years?

Long before thermometers, nature left its own temperature records. A climate scientist explains how ongoing global warming compares with ancient temperatures.

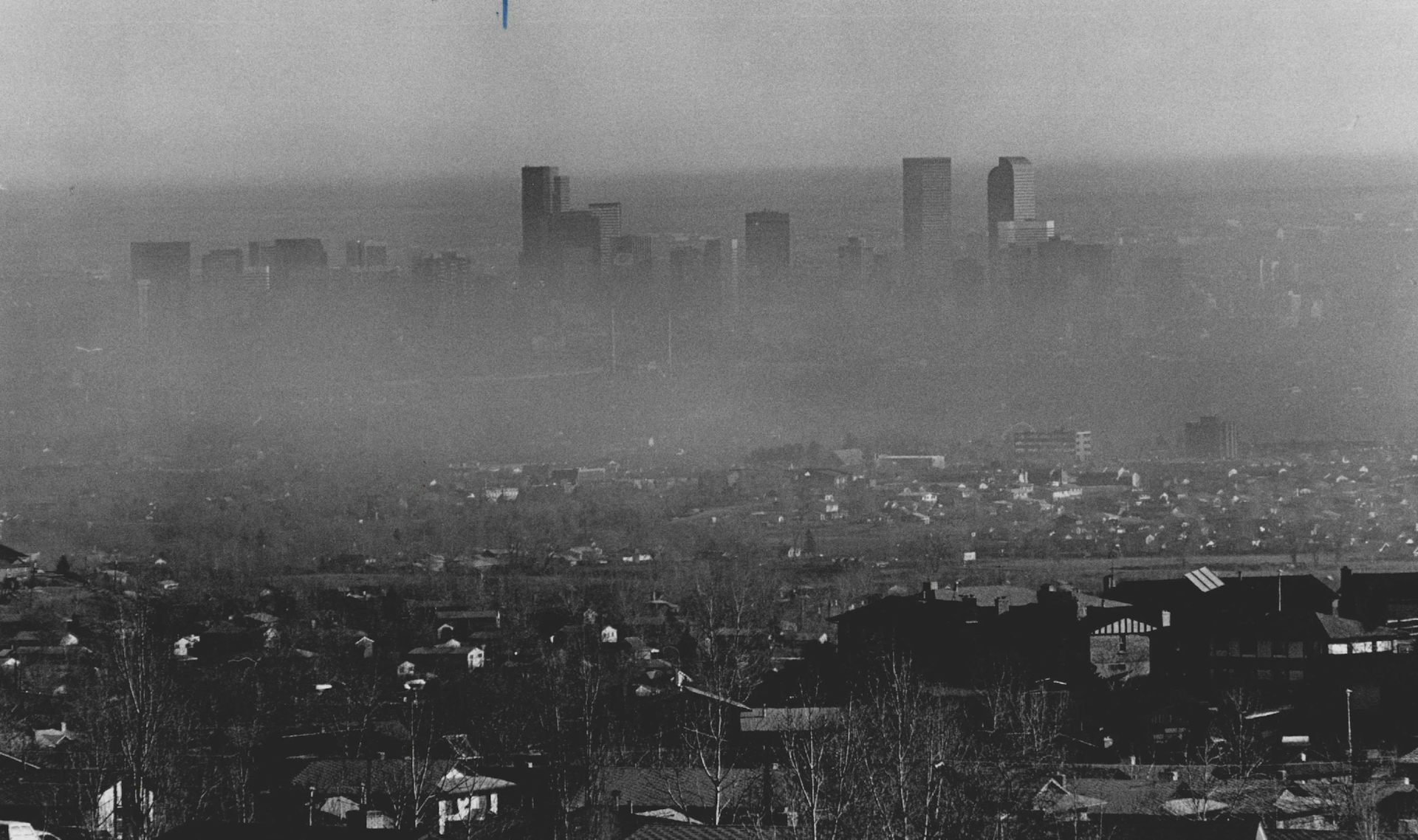

As scorching heat grips large swaths of the Earth, a lot of people are trying to put the extreme temperatures into context and asking: When was it ever this hot before?

Globally, 2023 has seen some of the hottest days in modern measurements, but what about farther back, before weather stations and satellites?

Some news outlets have reported that daily temperatures hit a 100,000-year high.

As a paleoclimate scientist who studies temperatures of the past, I see where this claim comes from, but I cringe at the inexact headlines. While this claim may well be correct, there are no detailed temperature records extending back 100,000 years, so we don’t know for sure.

Here’s what we can confidently say about when Earth was last this hot.

This is a new climate state

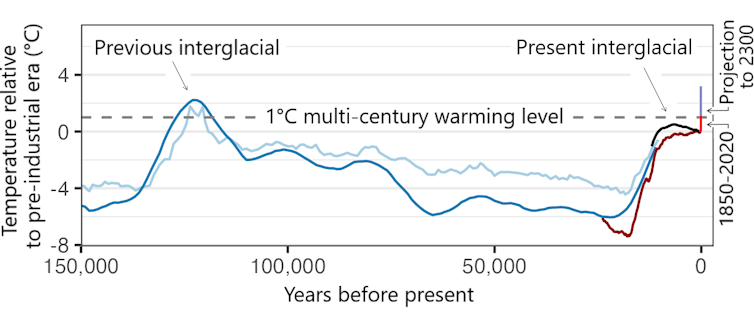

Scientists concluded a few years ago that Earth had entered a new climate state not seen in more than 100,000 years. As fellow climate scientist Nick McKay and I recently discussed in a scientific journal article, that conclusion was part of a climate assessment report published by the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) in 2021.

Earth was already more than 1 degree Celsius (1.8 Fahrenheit) warmer than preindustrial times, and the levels of greenhouse gases in the atmosphere were high enough to assure temperatures would stay elevated for a long time.

Even under the most optimistic scenarios of the future – in which humans stop burning fossil fuels and reduce other greenhouse gas emissions – average global temperature will very likely remain at least 1 C above preindustrial temperatures, and possibly much higher, for multiple centuries.

This new climate state, characterized by a multi-century global warming level of 1 C and higher, can be reliably compared with temperature reconstructions from the very distant past.

How we estimate past temperature

To reconstruct temperatures from times before thermometers, paleoclimate scientists rely on information stored in a variety of natural archives.

The most widespread archive going back many thousands of years is at the bottom of lakes and oceans, where an assortment of biological, chemical and physical evidence offers clues to the past. These materials build up continuously over time and can be analyzed by extracting a sediment core from the lake bed or ocean floor.

These sediment-based records are rich sources of information that have enabled paleoclimate scientists to reconstruct past global temperatures, but they have important limitations.

For one, bottom currents and burrowing organisms can mix the sediment, blurring any short-term temperature spikes. For another, the timeline for each record is not known precisely, so when multiple records are averaged together to estimate past global temperature, fine-scale fluctuations can be canceled out.

Because of this, paleoclimate scientists are reluctant to compare the long-term record of past temperature with short-term extremes.

Looking back tens of thousands of years

Earth’s average global temperature has fluctuated between glacial and interglacial conditions in cycles lasting around 100,000 years, driven largely by slow and predictable changes in Earth’s orbit with attendant changes in greenhouse gas concentrations in the atmosphere. We are currently in an interglacial period that began around 12,000 years ago as ice sheets retreated and greenhouse gases rose.

Looking at that 12,000-year interglacial period, global temperature averaged over multiple centuries might have peaked roughly around 6,000 years ago, but probably did not exceed the 1 C global warming level at that point, according to the IPCC report. Another study found that global average temperatures continued to increase across the interglacial period. This is a topic of active research.

That means we have to look farther back to find a time that might have been as warm as today.

The last glacial episode lasted nearly 100,000 years. There is no evidence that long-term global temperatures reached the preindustrial baseline anytime during that period.

If we look even farther back, to the previous interglacial period, which peaked around 125,000 years ago, we do find evidence of warmer temperatures. The evidence suggests the long-term average temperature was probably no more than 1.5 C (2.7 F) above preindustrial levels – not much more than the current global warming level.

Now what?

Without rapid and sustained reductions in greenhouse gas emissions, the Earth is currently on course to reach temperatures of roughly 3 C (5.4 F) above preindustrial levels by the end of the century, and possibly quite a bit higher.

At that point, we would need to look back millions of years to find a climate state with temperatures as hot. That would take us back to the previous geologic epoch, the Pliocene, when the Earth’s climate was a distant relative of the one that sustained the rise of agriculture and civilization.

Darrell Kaufman receives funding from the US National Science Foundation.

Read These Next

2025 was hotter than it should have been – 5 influences and a dirty surprise offer clues to what’s a

Solar cycles, sea ice and rising electricity use all play a role. So does an unhealthy surprise that…

Infusing asphalt with plastic could help roads last longer and resist cracking under heat

A research team has paved plastic-infused roads in Texas and Bangladesh, with promising results.

Trump’s climate policy rollback plan relies on EPA rescinding its 2009 endangerment finding – but wi

A federal judge dealt one blow to the effort when he found the administration had violated the law in…