Winning the Tour de France requires subtle physics, young muscles and an obscene amount of calories

Three scientists explain the biology and physics of what goes into one of the world’s most grueling races, the Tour de France.

The 2022 Tour de France is here. Starting in Copenhagen on July 1, the tour covers almost 2,100 miles (3,380 kilometers) over 24 days of riding through Denmark, Belgium, Switzerland and France. The tour is a feat of human athleticism, but to really understand how incredible it is to complete the race – much less win it – requires thinking about a unique blend of physics, biology and physiology. Mix those up just right and you get a Tour de France champion.

Over the years, The Conversation has published a series of stories covering the science of the Tour de France and elite athletics. Below are excerpts from three of those stories to help you better appreciate this spectacular race.

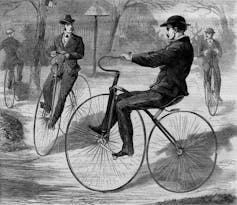

1. The biomechanics of riding a bike

Riding a bike is an easy thing to do once you learn, but the physics of how bikes and riders work together is surprisingly complicated. As Stephen Cain, a mechanical engineer at West Virginia University, explains, “A big part of balancing a bicycle has to do with controlling the center of mass of the rider-bicycle system.” Basically, you have to keep the center of mass above the wheels – otherwise you tip over.

“Bicycle riders can use two main balancing strategies: steering and body movement relative to the bike,” says Cain. Steering keeps the bike underneath you while body movements subtly shift your center of gravity. Cain and his colleagues ran a study to understand the difference between how novice and professional cyclists balance a bike, and as he says in his article, they found that “both novice and expert riders exhibit similar balance performance at slow speeds. But at higher speeds, expert riders achieve superior balance performance by employing smaller but more effective body movements and less steering.”

This fine-scale control is why the racers in the Tour de France barely look like they are steering at all.

Read more: The mysterious biomechanics of riding – and balancing – a bicycle

2. How many calories do Tour riders burn?

Think back to the last time you did some hard exercise and how hungry you were that evening. Now imagine how hungry you would be if you needed to ride your bike over 100 miles (165 km) and climb nearly 10,000 feet (about 3,050 meters) of elevation in less than five hours. This is what racers will have to do during Stage 12 of this year’s race as they traverse mountain passes through the French Alps. As Eric Goff, a sports physicist at the University of Lynchburg explains, the cyclists are going to need a lot of fuel to pull this off.

“To make a bicycle move, a Tour de France rider transfers energy from his muscles, through the bicycle and to the wheels that push back on the ground,” says Goff. Professional cyclists are in another league when it comes to producing power with their legs, but they are still limited by basic human biology. “Muscles, like any machine, can’t convert 100% of food energy directly into energy output,” explains Goff. “Muscles can be anywhere between 2% efficient when used for activities like swimming and 40% efficient in the heart.”

With mountains to climb and glory to claim, riders need to fuel their muscles with food. In his story, Goff calculates that over the course of the Tour de France, racers will burn an astonishing 120,000 colories – the equivalent of about 210 Big Macs.

Read more: Tour de France: How many calories will the winner burn?

3. Biology explains why professional athletes are young

When you watch the Tour de France, soccer’s World Cup or the Olympics, it’s common to see a young teenage phenom, but it’s rare for anyone over the age of 40 to be competing.

Roger Fielding, an aging and exercise researcher at Tufts University, writes that “old and young people build muscle in the same way.” But there is a biological reason no 50-year-old has ever won the Tour de France: “As you age, many of the biological processes that turn exercise into muscle become less effective.”

Muscles grow thanks to a number of complicated cellular pathways that are activated during exercise. When this network of receptors and signaling chemicals gets triggered, the body responds by increasing muscle size – and even makes some small tweaks to what genes are active. But as Fielding explains, in older people “the signal telling muscles to grow is much weaker for a given amount of exercise. These changes begin to occur when a person reaches around 50 years old and become more pronounced as time goes on.”

Many people can and do get into the best shape of their lives when they are in their 50s or 60s. But the fact that it is harder to get fit as you age is a major reason why it’s so important for older people to exercise – and why you won’t see any retirees leading the peloton in the Tour de France.

Read These Next

AI’s growing appetite for power is putting Pennsylvania’s aging electricity grid to the test

As AI data centers are added to Pennsylvania’s existing infrastructure, they bring the promise of…

Why US third parties perform best in the Northeast

Many Americans are unhappy with the two major parties but seldom support alternatives. New England is…

The cost of casting animals as heroes and villains in conservation science

New research shows how these storytelling choices can distort science – and how to move beyond them.