Women's History Month: 5 groundbreaking researchers who mapped the ocean floor, tested atomic theori

Discover the stories of five trailblazing women – Tharp, Nice, Tu, Noether and Wu – who worked in STEM during the 20th century.

Behind some of the most fascinating scientific discoveries and innovations are women whose names might not be familiar but whose stories are worth knowing.

Of course, there are far too many to all fit on one list.

But here are five profiles from The Conversation’s archive that highlight the brilliance, grit and unique perspectives of five women who worked in geosciences, math, ornithology, pharmacology and physics during the 20th century.

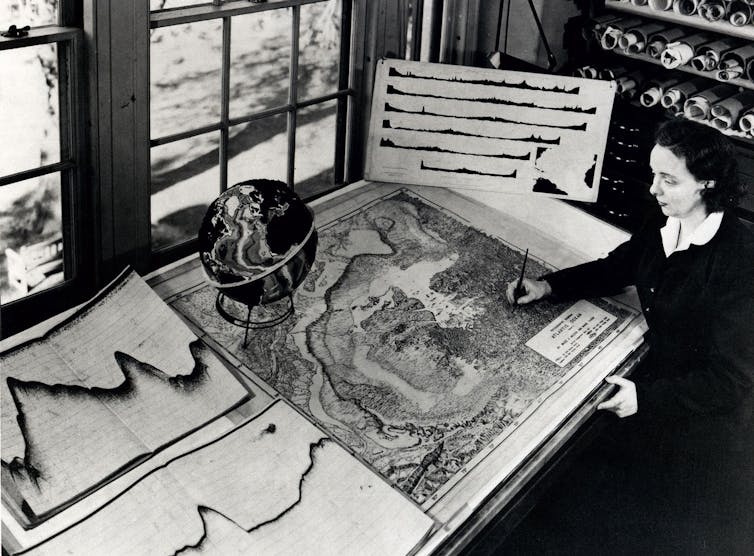

1. Revealing and mapping the ocean floor

As late as the 1950s, wrote Wesleyan University geoscientist Suzanne OConnell, “many scientists assumed the seabed was featureless.”

Enter Marie Tharp. In 1957, she and her research partner started publishing detailed hand-drawn maps of the ocean floor, complete with rugged mountains, valleys and deep trenches.

Tharp was a geologist and oceanographer. Aboard research ships, she would carefully record the depth of the ocean, point by point, using sonar. One of her innovations was to translate this data into topographical sketches of what the seafloor looked like.

Her discovery of a rift valley in the North Atlantic shook the world of geology – her supervisor on the ship dismissed her idea as “girl talk,” and Jacques Cousteau was determined to prove her wrong. But she was right, and her insight was a key contribution to plate tectonic theory. That’s part of why, OConnell writes, “I believe Tharp should be as famous as Jane Goodall or Neil Armstrong.”

2. Sympathetic observation of bird behavior

Margaret Morse Nice was a field biologist who got into the minds of her study subjects to garner new insights into animal behavior. Most famously she observed song sparrows in the 1920s and ‘30s.

Rochester Institute of Technology professor of science, technology and society Kristoffer Whitney recounted what Nice called her “phenomenological method,” acknowledging the obvious “affection and anthropomorphism” you can see in her descriptions.

“When I first studied the Song Sparrows,” Nice wrote, “I had looked upon Song Sparrow 4M as a truculent, meddlesome neighbor; but … I discovered him to be a delightful bird, spirited, an accomplished songster and a devoted father.”

Despite earning no advanced degrees and being considered an amateur, Nice promoted innovations like the “use of colored leg bands to distinguish individual birds,” gained the respect of her better-known peers and enjoyed a long, successful career.

3. A medical researcher in Maoist China

At the height of China’s Cultural Revolution, a young scientist named Tu Youyou headed a covert operation called Project 523 under military supervision. One of her team’s goals was to identify and systematically test substances used in traditional Chinese medicine in an effort to vanquish chloroquine-resistant malaria.

Historian Jia-Chen Fu described how “contrary to popular assumptions that Maoist China was summarily against science and scientists, the Communist party-state needed the scientific elite for certain political and practical purposes.”

Tu followed a hunch about how to extract an antimalarial compound from the qinghao or artemisia plant. By 1971, her team had successfully “obtained a nontoxic and neutral extract that was called qinghaosu or artemisinin.” In 2015, she was honored with a Nobel Prize.

Read more: The secret Maoist Chinese operation that conquered malaria – and won a Nobel

4. A mathematician who wouldn’t be diverted

Not everyone gets called a “creative mathematical genius” by Albert Einstein. But Emmy Noether did.

Mathematician Tamar Lichter Blanks wrote about the roadblocks Noether faced as a Jewish woman who wanted to pursue a math career in early 1900s Germany. For a while, Noether supervised doctoral students without pay and taught university courses listed under the name of a male colleague.

All the while, she conducted her own research in theoretical physics, contributing to Einstein’s theory of relativity. Her most revolutionary work was in ring theory and is still pondered by mathematicians today.

Noether died less than two years after emigrating to the U.S. to escape the Nazis.

5. Testing nuclear theories one by one

While sometimes called the “Chinese Marie Curie” in her home country, nuclear physicist Chien-Shiung Wu is less well-known in the U.S., where she did the bulk of her work. Rutgers University-Newark physicist Xuejian Wu considered Chien-Shiung Wu (no relation) “an icon” who inspired his own career path.

As a grad student, Wu traveled by steamship to California in 1936, where she fell in love with atomic nuclei research at UC Berkeley, home of a brand new cyclotron. She worked on the Manhattan Project during World War II.

Among her many accomplishments, Wu’s careful experimental work discovered what’s called parity nonconservation – that is, that a physical process and its mirror reflection are not necessarily identical. Her colleagues who focused on the theoretical side of this breakthrough won the 1957 Nobel Prize in physics, but Wu was overlooked.

Read more: New postage stamp honors Chien-Shiung Wu, trailblazing nuclear physicist

Editor’s note: This story is a roundup of articles from The Conversation’s archives.

Read These Next

Why US third parties perform best in the Northeast

Many Americans are unhappy with the two major parties but seldom support alternatives. New England is…

Abortion laws show that public policy doesn’t always line up with public opinion

Polls indicate majority support for abortion rights in most states, but laws differ greatly between…

Detroit was once home to 18 Black-led hospitals – here’s how to understand their rise and fall

In the early 20th century, Detroit’s Black medical professionals created a network of health care…