Nocturnal dinosaurs: Night vision and superb hearing in a small theropod suggest it was a moonlight

By looking at the eye bones and ear canals of extinct dinosaurs, researchers show that a small ancient predator likely hunted at night and had senses as good as a modern barn owl.

Today, barn owls, bats, leopards and many other animals rely on their keen senses to live and hunt under the dim light of stars. These nighttime specialists avoid the competition of daylight hours, hunting their prey under the cloak of darkness, often using a combination of night vision and acute hearing.

But was there nightlife 100 million years ago? In a world without owls or leopards, were dinosaurs working the night shift? If so, what senses did they use to find food and avoid predators in the darkness? To better understand the senses of the dinosaur ancestors of birds, our team of paleontologists and paleobiologists scoured research papers and museum collections looking for fossils that preserved delicate eye and ear structures. And we found some.

Using scans of fossilized dinosaur skulls, in a paper published in the journal Science on May 6, 2021, we describe the most convincing evidence to date for nocturnal dinosaurs. Two fossil species – Haplocheirus sollers and Shuvuuia deserti – likely had extremely good night vision. But our work also shows that S. deserti also had incredibly sensitive hearing similar to modern-day owls. This is the first time these two traits have been found in the same fossil, suggesting that this small, desert-dwelling dinosaur that lived in ancient Mongolia was probably a specialized night-hunter of insects and small mammals.

Looking to theropods

By studying fossilized eye bones, one of us, Lars Schmitz, had previously found that some small predatory dinosaurs may have hunted at night. Most of these potentially nocturnal hunters were theropods, the group of three-toed dinosaurs that includes Tyrannosaurus rex and modern birds. But to date, fossils for only 12 theropod species included the eye structures that can tell paleontologists about night vision.

Our team identified four more species of theropods with clues for their sense of vision – for a total of 16. We then looked for fossils that preserve the structures of the inner ear and found 17 species. Excitingly, for four species, we were able to get measurements for both eyes and ears.

Eye bones built for night vision

Scleral ossicles are thin, rectangular bone plates that form a ring-like structure surrounding the pupils of lizards as well as birds and their ancestors – dinosaurs. Scleral rings define the largest possible size of an animal’s pupil and can tell you how well that animal can see at night. The larger the pupil compared to the size of the eye, the better a dinosaur could see in the dark.

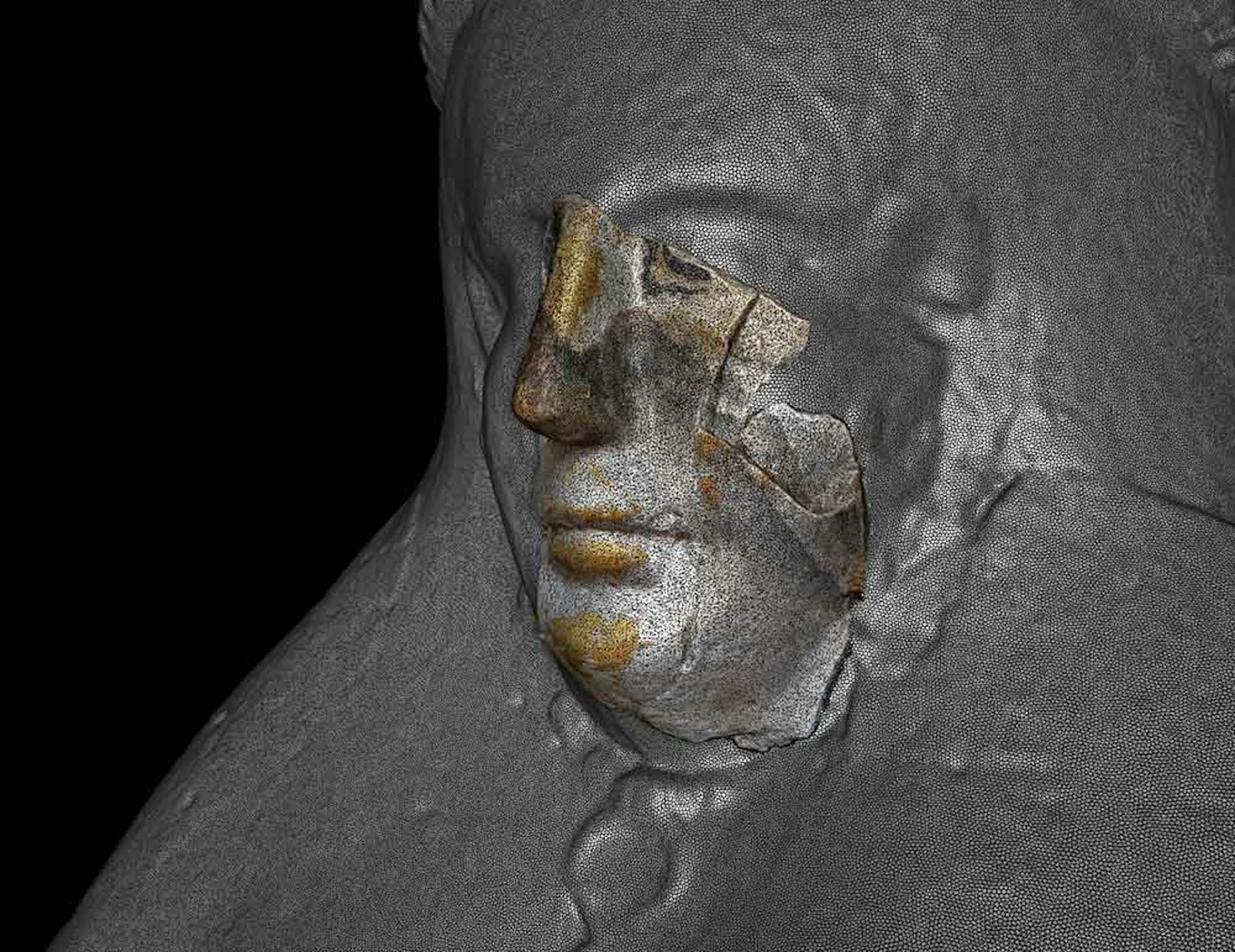

Since the individual bony ossicles of these rings fell apart after these animals died more than 60 million years ago, our team made scans of the fossils and then digitally reconstructed the eyes. Of all the theropods we examined, H. sollers and S. deserti had some of the proportionally largest pupils.

S. deserti‘s pupil made up more than half of its eye, very similar to night-vision specialists that live today like geckos and nightjars. Our team then compared the fossils to 55 living species of lizards and 367 species of birds with known day or night activity patterns. According to the statistical analyses our team performed, there is a very high chance – higher than 90% – that H. sollers and S. deserti were nocturnal.

But those were not the only two theropods our team looked at. Our analysis also found a few other likely nighttime specialists – such as Megapnosaurus kayentakatae – as well as daylight specialists like Almas ukhaa. But we also found some species – like Velociraptor mongoliensis – with eyesight seemingly adapted for medium light levels. This might suggest that they hunted around dawn or dusk.

Incredible ears of a dinosaur

In today’s nocturnal animals, hearing can be as important as keen eyesight. To figure out how well these extinct dinosaurs could hear, we scanned the skulls of 17 fossil theropods to decipher the structure of their inner ears and then compared our scans to the ears of modern animals.

All vertebrates have a tube-like canal called the cochlea deep in their inner ear. Studies of living mammals and birds show that the longer this canal, the wider the range of frequencies an animal can hear and the better they can hear very faint sounds.

Our scans showed that S. deserti had an extremely elongated inner ear canal for its size – also similar to that of the living barn owl and proportionally much longer than all of the other 88 living bird species we analyzed for comparison. Based on our measurements, among dinosaurs, we found that predators had generally better hearing than herbivores. Several predators – including V. mongoliensis – also had moderately elongated inner ears, but none rivaled S. deserti’s.

The life of a nocturnal dinosaur

By studying the sensory abilities of dinosaurs, paleontologists like us not only are learning what species roamed the night, but can also begin to infer how these dinosaurs lived and shared resources.

S. deserti had extreme night vision and sensitive hearing, and this little dinosaur probably used its incredible senses to hunt prey at night. It could likely hear and follow rustling from a distance before visually detecting its prey and digging it up from the ground with its short single-clawed arms. In the dry, desert-like habitats of millions of years ago, it might have been an evolutionary advantage to be active in the cooler temperatures of the night.

But according to our analysis, S. deserti wasn’t the only dinosaur active at night. Other dinosaurs like V. mongoliensis and the plant-eating Protoceratops mongoliensis both lived in the same habitat and had some level of night vision.

Paleontologists currently do not know the full suite of animals that shared S. deserti’s extreme nocturnal lifestyle in the ancient deserts of Mongolia – it is rare to find fossils with the right bones intact that allow paleontologists to investigate their senses. However, the presence of a specialized night forager highlights that much like today, some dinosaurs avoided the dangers and competition of daylight hours and roamed under the stars.

[Get the best of The Conversation, every weekend. Sign up for our weekly newsletter.]

Jonah Choiniere receives funding from the National Research Foundation of South Africa.

Roger Benson receives funding from the European Research Council, National Environments Research Council and Leverhulme Trust.

Lars Schmitz does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organization that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

Read These Next

How a largely forgotten Supreme Court case can help prevent an executive branch takeover of federal

An FBI raid on a Georgia elections facility has sparked concern about Trump administration interference…

3D scanning and shape analysis help archaeologists connect objects across space and time to recover

Digital tools allow archaeologists to identify similarities between fragments and artifacts and potentially…

The intensity and perfectionism that drive Olympic athletes also put them at high risk for eating di

Athletes in sports where weight and body image come into play, such as figure skating and wrestling,…