How new voters and Black women transformed Georgia's politics

Georgia once had 'the South's most racist governor,' a man endorsed by the KKK. Now its senators are a Black pastor and a Jewish son of immigrants. A scholar of minority voters explains what happened.

In July 1964, Georgia restaurateur Lester Maddox violated the newly passed Civil Rights Act by refusing to serve three Black Georgia Tech students at his Pickrick Restaurant in Atlanta. Although this new federal law banned discrimination in public places, Maddox was determined to maintain a whites-only dining room, arming white customers with pick handles – which he called “Pickrick drumsticks” – to threaten Black customers who tried to dine there.

Endorsed by the Ku Klux Klan in his successful 1974 bid for the governorship, Maddox was once called “the South’s most racist governor.” But hostile treatment of minorities has often been Georgia’s chosen style of politics.

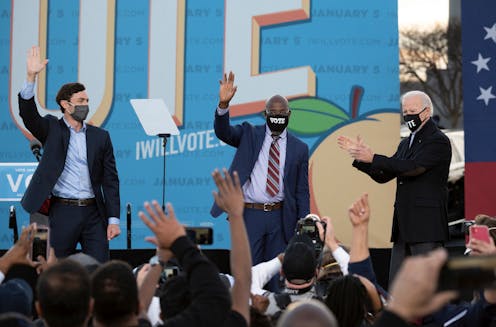

Until recently. On Jan. 5, Georgians chose a Black pastor and a 33-year-old son of Jewish immigrants – Democrats Raphael Warnock and Jon Ossoff – to represent them in the Senate. They also elected Democrat Joe Biden for president in November.

Georgia’s turn from blood red to deep purple gave Democrats their slender majority in the Senate, surprising Americans on both sides of the aisle. This historic moment was a long time coming.

I am a political scientist who studies American politics, with a focus on minority voters and urban politics. In my research, I have examined the peculiar mix of factors that led to Warnock’s and Ossoff’s victories, chiefly an electorate that had been diversifying for years and the effort of many hardworking Black women.

The New South

The elections of Biden, Warnock and Ossoff are the culmination of a years long tug of war among the members of Georgia’s racially, ethnically and ideologically diverse electorate.

Georgia’s demographics are changing fast. In 2019, it was ranked fifth among U.S. states experiencing an influx of newcomers. According to census data, 284,541 residents arrived from out of state that year.

Many of Georgia’s newest voters come from groups that lean Democratic: minorities, young people, unmarried women. Between 2000 and 2019, Georgia’s [Black population increased by 48%], mostly because people moved there from out of state. African Americans now make up 30% of Georgia’s population. The Latino population increased by 14% since 2000, and Latinos now comprise 9% of Georgians.

Meanwhile, Georgia’s white population declined slightly, from 57% in 2010 to 54% in 2019. Non-Latino whites are projected to be a numerical minority in Georgia within the next decade.

Just 30% of white Georgia voters chose Warnock and Ossoff on Jan. 5. But the pair, who often campaigned together, both won about 90% of the Black vote and about half of Latinos. Two-thirds of Asian Americans – a small but fast-growing electoral force in Georgia – voted for Ossoff, Warnock and Biden, exit data shows.

Black women bring new voters

Georgia’s changing electorate began producing new kinds of elected officials a few years back.

In 2017 Bee Nguyen, the daughter of Vietnamese refugees, became the first Vietnamese American elected to the Georgia state Legislature. She won the seat vacated by Democrat Stacey Abrams when Abrams ran for governor after a decade in the Statehouse.

Abrams lost her 2018 race to become America’s first Black female governor by 55,000 votes, or 1.4 percentage points. Analysts attributed her defeat, in part, to low turnout rates, especially among Black voters.

This – along with credible allegations of voter suppression – is one reason Abrams soon ramped up her voter registration effort.

Abrams had begun organizing voters when campaigning for the Legislature in 2006. By 2018, her nonpartisan voter registration group, the New Georgia Project, was working with the National Coalition on Black Civic Participation, Georgia Coalition for the People’s Agenda, Pro Georgia, the Black Voters Matter Fund, Georgia STAND-UP and others to mobilize Black voters.

These groups, all led by Black women – Nse Ufot, Melanie Campbell, Helen Butler, Tamieka Atkins, LaTosha Brown and Deborah Scott, respectively – helped register an additional 800,000 Georgia voters between 2018 and 2020. Black voters and young people were particular targets.

Exactly two years after Abrams’ November 2018 loss, Joe Biden won Georgia by 13,000 votes – the first Democratic presidential candidate to win there since Bill Clinton in 1992. Warnock and Ossoff benefited from all these new Georgia voters, too.

Georgia’s Democratic electorate is young, Black, Latino and Asian American. It is the new South – and Black women helped create it.

[Get the best of The Conversation, every weekend. Sign up for our weekly newsletter.]

Record turnout

Ossoff and Warnock were always going to have a hard race in Georgia, but the nature of Georgia’s runoff elections compounded their underdog status.

In Georgia, if neither candidate wins 50% or more of the vote in the general election, the top two candidates compete in a runoff. This system supposedly ensures that those elected have the support of a majority of voters, but in practice minorities usually lose to whites because of racially polarized voting. Historically, white and Black Georgians vote for the candidate from their racial group. Because white turnout was higher, white conservative candidates have won.

The Jan. 5 runoff upended tradition. Over 4.4 million Georgians voted – a 60% turnout rate, almost doubling that of Georgia’s last Senate runoff, in 2008.

In this year’s runoff election, Democrats went to the polls in droves during early voting, giving Warnock and Ossoff an edge. Republican turnout lagged in mostly white rural areas during the early voting period. It increased statewide on Election Day, but Democrats kept voting that day, too. Republicans could not make up the difference.

Before Warnock and Ossoff, Georgia had never elected an African American to a statewide office. And it had never elected a Jewish senator.

Republican failures

The Republican Party had a role in its losses in Georgia, too.

Some analysts blame Trump for low Republican turnout in the Senate runoff. After his loss in November, he claimed Georgia’s elections were “rigged” against his party. Then-Senate Majority Leader Mitch McConnell’s opposition to increasing stimulus checks from $600 to $2,000 in a time of acute joblessness, poverty and hunger also likely hurt the Republican Senate candidates, David Perdue and Kelly Loeffler.

Ultimately, though, it was Georgia’s changing electorate that put Democrats in office. The 2022 midterm elections will start to show how far Georgia has really come from the politics of Lester Maddox’s Pickrick Restaurant.

Sharon Austin does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organization that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

Read These Next

How the Emerald Isle shaped the Steel City – Pittsburgh’s rich Irish history

Long before Pittsburgh’s modern Irish celebrations existed, Irish immigrants helped shape the city…

I was teaching virtue and knowledge while lying on the side

While rationalizing deception is easy to do, developing the virtue of truthfulness is not.

As the Oscars approach, Hollywood grapples with AI’s growing influence on filmmaking

AI tools can now generate movie scenes, resurrect lost footage and replace entry-level jobs – forcing…