A brief history of the term ‘president-elect’ in the United States

The term can be traced back to the Founding Fathers.

On Jan. 20, Joe Biden will be sworn in as president of the United States. Until then, he is president-elect of the United States.

But what exactly does it mean to be president-elect of the United States?

As a lawyer and philosopher who studies word meaning, I have researched the meaning and history of the term “president-elect” using publicly available resources like the Corpus of Historical American English – a searchable database of over 400 million words of historical American English text. I’ve also used Founders Online, which makes freely available many documents written by the nation’s founders.

“President-elect” is not a term that is legally defined in U.S. law. Rather, the term’s meaning has developed over time through its use by the public. Its use can be traced all the way back to George Washington.

The founders used it

In 1793, Washington wrote a letter concerning his upcoming second inauguration as president in which he referred to himself as “president-elect.”

Numerous letters by the Founding Fathers contain the term “president-elect” in connection with the 1796 presidential election.

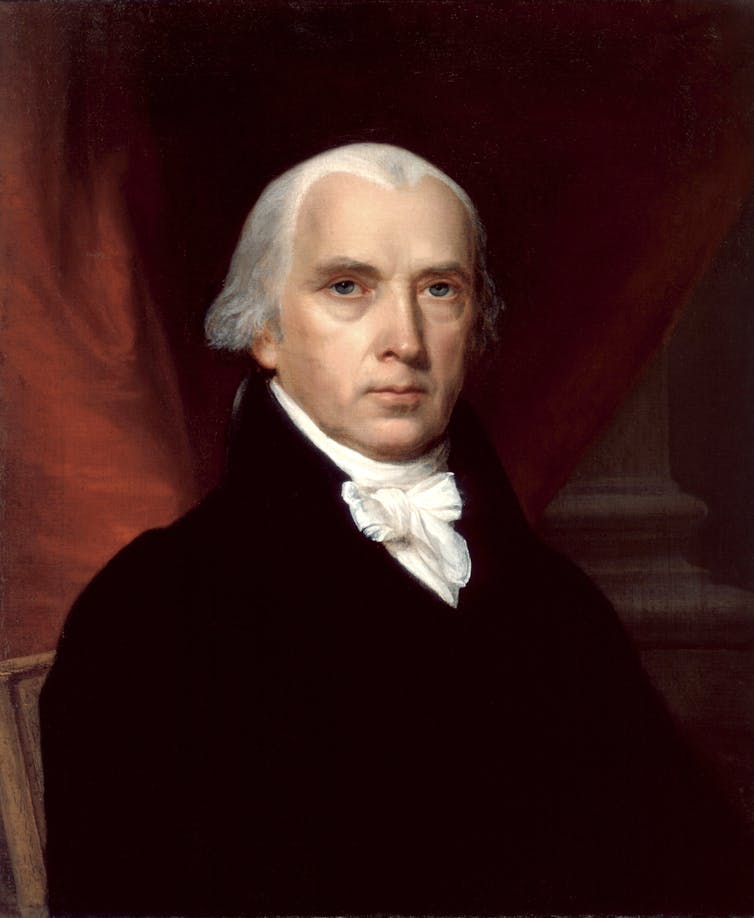

Of particular note is a letter from James Madison to Thomas Jefferson, sent on Christmas Day 1796. Wrote Madison:

“Unless the Vermont election of which little has of late been said, should contain some fatal vice, in it, Mr. Adams may be considered as the President elect. Nothing can deprive him of it but a general run of the votes in Georgia, Tenissee & Kentucky in favor of Mr. Pinkney, which is altogether contrary to the best information.”

The letter provides insight into how the term “president-elect” was understood at that time. Madison asserts that John Adams can be considered the president-elect, even though the results from at least four states – Vermont, Georgia, Tennessee and Kentucky – do not appear to have been known to Madison yet.

Madison’s comments suggest that it was appropriate at that time to consider someone president-elect once it appeared likely that they had secured enough votes to win the Electoral College.

Madison’s use of the term was similar to its use in a letter that John Adams wrote to Abigail Adams five days earlier, on Dec. 20, 1796.

John Adams suggests people have been toasting him “under the Title” of “The President elect.” The letter was written two-and-a-half months prior to Adams’ inauguration, which took place on March 4, 1797.

19th- and 20th-century news media used it

Beginning in the latter half of the 1800s, major news outlets regularly referred to the person who appeared to have won the presidency as “president-elect” soon after popular elections were complete.

In a post-election story published on Nov. 20, 1880, a New York Times article bore the headline “Gen. Garfield at Home: An Hour with the President-Elect at Mentor.”

In subsequent years, the Times referred to apparent election victors as “president-elect” even sooner, including Grover Cleveland on Nov. 13, 1892 and William McKinley on Nov. 19, 1896.

Other longstanding U.S. publications behaved similarly. The Nation magazine called William Howard Taft the “president-elect” on Nov. 12, 1908, and did the same with Woodrow Wilson on Nov. 21, 1912.

Significantly, all these references were made back when electors did not formally cast their votes for president until the second Monday in January and presidential inaugurations did not happen until early March. This shows that there is a lengthy history of using the term “president-elect” long before electors cast their votes.

In the 1930s, Inauguration Day was moved into January and electors began casting their votes in December, but this does not seem to have had much effect on when and how the term “president-elect” was used by the public.

For example, Time magazine ran a story on “President-elect” Herbert Hoover on Nov. 19, 1928 (before Inauguration Day was changed), and a story on “President-elect” Franklin Delano Roosevelt on Nov. 16, 1936 (after Inauguration Day was changed).

Congress used it

While the term “president-elect” is not defined in federal law, Congress eventually incorporated it into the U.S. Constitution with the adoption of the 20th Amendment in 1933. That amendment states that “If, at the time fixed for the beginning of the term of the President, the President elect shall have died, the Vice President elect shall become President.”

[Get facts about coronavirus and the latest research. Sign up for The Conversation’s newsletter.]

When Congress does not define a term used in its legislation, it is customary for courts to interpret that word in accordance with its ordinary meaning. Thus, Congress’ decision not to define the term “president-elect” gives us reason to interpret it in accordance with its customary meaning throughout U.S. history.

Everybody uses it

In recent years, it has remained customary for news outlets and politicians to refer to a presidential candidate as president-elect as soon as it appears that the candidate has gained enough Electoral College votes to become president.

CNN, The New York Times and then-President Barack Obama all referred to Donald Trump as president-elect by Nov. 9, 2016, just a day after the 2016 general election.

In 2020, by the Saturday after the general election, Nov. 7, 2020, many major news sources, including the Associated Press and Fox News, had declared Joe Biden president-elect, thus adding to the long history of the term.

Mark Satta does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organization that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

Read These Next

US is less prone to oil price shocks than in past decades

Oil prices affect the US economy differently than in past decades. Nowadays, the US is less reliant…

Mobile clinics offer a practical way to improve health care access in maternity care deserts

Mobile health clinics are a practical but underused solution to the growing number of maternity care…

What James Madison can teach Americans about religious freedom today

For Madison, religious freedom was not a tool for political domination. Rather, he saw it as a constitutional…