Executions don't deter murder, despite the Trump administration's push

The most commonly used justification for capital punishment is not actually supported by evidence.

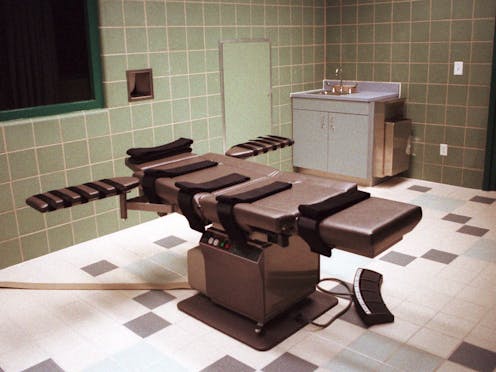

Three more federal inmates are slated to be executed before the end of President Donald Trump’s term, though the first received a stay hours before she was slated to die on Jan. 12. Ten have already been put to death since the Trump administration announced in July 2019 that it would resume executions after a 17-year suspension.

It’s not clear why the administration has done so many in such a short time after a long break. Officially it claims to be “bringing justice to victims of the most horrific crimes.”

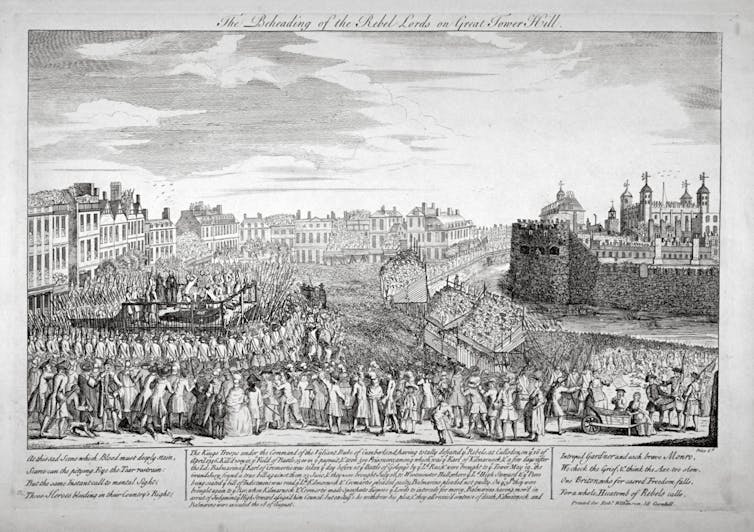

Capital punishment has a long history, which may even extend to prehistoric times, when early humans sought ways to rid their communities of incorrigible troublemakers.

In modern times, governments use what German social theorist Max Weber called their “monopoly on legitimate force” to conduct executions. From my decades as a psychologist and biologist, I identify four basic justifications governments use for killing their citizens:

- Removing dangerous people from society,

- Justice (or revenge), and the satisfaction it can bring to a victim’s family,

- Demonstrating the power of the state, and

- Deterrence, or discouraging others from committing heinous crimes for fear they too may be executed.

Death penalty advocates most frequently focus on deterrence – but as research including my own work shows, it has not been shown to be effective.

A brief history

By the end of the 18th century, England specified 220 different offenses – mostly thefts of different kinds of property – that were punishable by death. The expressed intent of England’s “Bloody Code” was deterrence.

“Men are not hanged for stealing horses,” wrote the Marquess of Halifax, a 17th-century British nobleman, “but that horses may not be stolen.” Nevertheless, horses were stolen, and poor people were hanged for stealing them – or a quill pen or a bolt of cloth.

The idea of deterrence lasted another couple hundred years: In the 1970s, economist Isaac Ehrlich claimed that every execution saved eight innocent lives by preventing other murders. His hugely influential work has subsequently been challenged, not least because it relied on national trends and did not distinguish between crimes in states that had, or lacked, capital punishment.

In 2020, the U.S. government still has the death penalty on the books for certain crimes, as do 30 states. These laws face ethical and logical criticism, such as the idea of a government killing people to reinforce the idea that people shouldn’t kill people. They also are often found to be unjust, sometimes executing innocent people and used disproportionately in cases involving racial minorities and poor people. But most importantly, and, despite what its advocates say, capital punishment doesn’t deter murders.

Research and evidence

Research has shown that, while there have been changes in murder rates over time, those changes aren’t related to whether a government has – or doesn’t have – the death penalty. By far the most authoritative report to date came from the National Research Council, an arm of the National Academy of Sciences, in 2012. It found there was no credible evidence that capital punishment has any effect on homicide rates.

Of course, there is no ethical way to devise a scientific experiment to test whether capital punishment deters murder. But an impressive array of correlations exists, which together are enough to make a highly credible, informed judgment. For example:

In 1976, Canada abolished capital punishment and the U.S. restored it. Yet Canada’s murder rate remained roughly the same as that of the U.S..

Hong Kong and Singapore are two demographically and economically comparable city-states. Hong Kong abolished executions, whereas Singapore did not, yet murder rates have remained remarkably similar in both.

New York and Texas had comparable murder statistics and execution rates as of 1992. As crime peaked nationally, the two states’ responses differed: Texas ramped up its executions, while there were no executions in New York from 1992 to 2003. Their results were different, too: New York’s homicide rate declined by 62.9%, far more than the drop in Texas of 49.6% over those years.

Manhattan, the Bronx and Brooklyn are broadly similar demographically, and also share the same police force and local and state legal systems. From 1995 to 2004, county prosecutors in Manhattan and the Bronx did not enforce capital punishment, but those in Brooklyn did. Homicides declined in all three boroughs of New York City, consistent with nationwide trends, but the Manhattan and Bronx declines were significantly greater.

If the threat of capital punishment were an effective deterrent, then homicides would tend to decline immediately following executions, especially those that received substantial public attention. Yet evidence indicates that executions may actually increase the frequency of murders.

It is tempting to think that severe penalties would effectively reduce crime, with the most extreme penalty – death – reducing the most serious crime, notably murder. But there is simply no compelling evidence that it does.

[Get our most insightful politics and election stories. Sign up for The Conversation’s Politics Weekly.]

David P. Barash ne travaille pas, ne conseille pas, ne possède pas de parts, ne reçoit pas de fonds d'une organisation qui pourrait tirer profit de cet article, et n'a déclaré aucune autre affiliation que son organisme de recherche.

Read These Next

What James Madison can teach Americans about religious freedom today

For Madison, religious freedom was not a tool for political domination. Rather, he saw it as a constitutional…

I’ve studied MAGA rhetoric for a decade, and this is what I see in Hegseth’s boasts, action-movie on

Why does Defense Secretary Pete Hegseth brag and gloat in his statements about the Iran war? In the…

Big beautiful refund? 5 tax code changes that may put more money in your pocket

Those who stand to benefit from the changes in tax code include workers who earn tips, those receiving…