From Macedonia to America: Civics lessons from the former Yugoslavia

Demonstrations by Macedonian villagers in the 1980s, which helped spark the end of Communist rule in the former Yugoslavia, hold vital lessons for Americans peacefully protesting for police reform.

Americans protesting police violence may find inspiration in the activism of Macedonian citizens in the last years of Communist rule in Yugoslavia.

In August 1987, Communist party leaders imposed, without local input, a major infrastructure project on the village of Vevcani: to redirect water from its springs to other settlements. The villagers saw the lack of consultation as a betrayal. They also viewed the loss of control over water resources as a threat to their children’s futures.

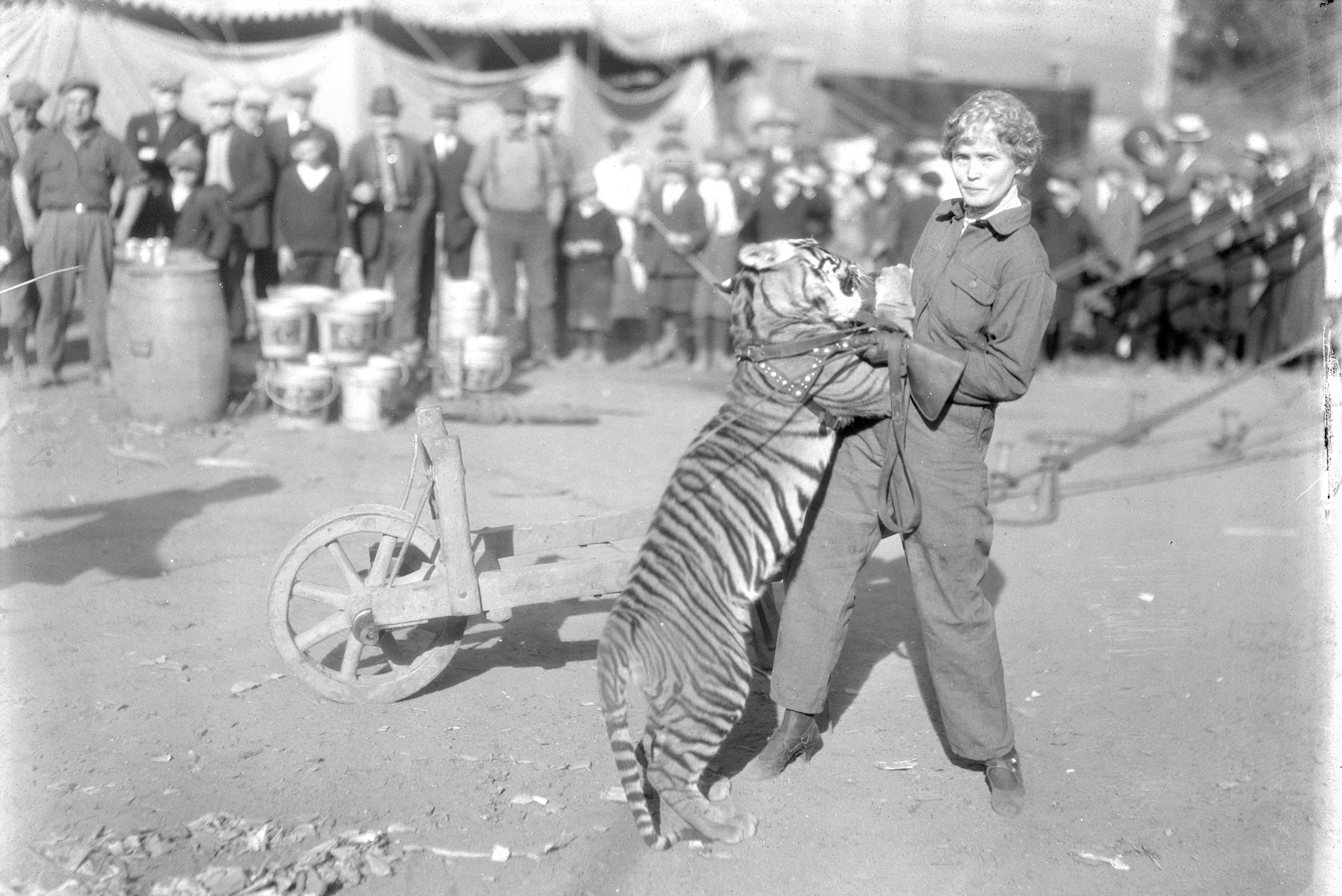

So they resorted to civil disobedience. They blocked village streets with makeshift barricades and their bodies. They held up pictures of Tito, the Yugoslav leader who had died seven years earlier, to signal their loyalty to the country’s ideals. Their fight was against the abuse of state power.

The authorities responded by deploying the militia. They used physical force, including stun batons, to disperse the peaceful demonstrations. Participants, mostly women and children, were physically injured or psychologically traumatized.

As a professor of global studies, I have been researching the last days of Yugoslavia, before the country came apart in the ethnic violence of the early 1990s.

I’ve found that the 1987 “Vevcani affair” was the spark for a creative campaign of nonviolence that catalyzed opposition countrywide to the Communist regime across Yugoslavia.

And this summer I also found that Vevcani holds what I believe to be an important lesson for Americans peacefully protesting for police reform and government accountability.

From Macedonia to Lafayette Square

In early June, just before President Donald Trump walked from the White House to St. John’s Church for a photo op, U.S. Park Police used chemical irritants and rubber bullets to disperse peaceful protesters in Lafayette Square.

Watching this footage and hearing testimony from people targeted by the police, I was transported to Vevcani and the few images that exist depicting the militia assaults.

I found that the villagers’ descriptions of chokeholds, electric shocks and unwarranted detention had new and troubling resonance, as the Trump administration has deployed paramilitary units to quash protests not only in Lafayette Square but in cities across the United States.

When asked who gave the order to use force in Lafayette Square, White House Press Secretary Kayleigh McEnany pointed to Attorney General William Barr. Barr denied this, indicating that a law enforcement officer made the “tactical” decision. In congressional testimony in early July, Secretary of Defense Mark Esper stated that it was “still unclear” who gave the order.

Witnessing the Trump administration’s obfuscation and shifting of the blame invites parallels with the last gasp of the Yugoslav regime. Faced with citizen anger, the ruling party spewed misinformation to sow doubt about the protesters’ character and motives.

The party retaliated against village leaders, blocking access to educational or employment opportunities for them and their families. The regime deployed all its state machinery to show strength and break the will of the movement.

It didn’t work.

Growth of a mass movement

Vevcani villagers defied further efforts to silence them. They pursued a campaign of creative, nonviolent protest to build a coalition of allies across Yugoslavia.

They enlisted artists, poets and journalists to their cause.

Theater director Vladimir Milcin, for example, published a powerful critique of Macedonian intellectuals’ complicity with the regime and helped Vevcani’s amateur theater troupe reach broader audiences.

Slovenian poet Dane Zaec spoke out against government-sponsored violence. And Montenegrin filmmaker Krsto Skanata told Vevcani’s story in his award-winning short film, “Thank you for Freedom.”

The villagers’ commitment to nonviolence and civility, and to the presentation of firsthand, eye-witness testimony of government brutality, contrasted sharply with the regime’s bullying tactics of bluster and denial.

By persistently asking party leaders a simple, direct question – who gave the order to use violence? – the villagers confronted authoritarianism. They called out those they judged responsible, listing their names on a mock gravestone in the village square.

Their solidarity was fully displayed in May 1989. Vevcani’s leaders organized a mass march from the village to the central party headquarters in Skopje, over 100 miles away. More than 2,000 people assembled to demand a face-to-face meeting with the party leadership and a full inquiry into the infrastructure project.

By this time, a number of influential, reform-minded journalists and politicians in Macedonia had embraced the villagers’ cause.

Within a month, following a parliamentary debate and broad media coverage, the government’s interior minister and his deputy were forced to resign. By the end of 1989, the party had committed to reform, including a secret ballot to elect a new party head. An economist, Petar Gosev, won and led the reformers to introduce multiparty elections in 1990.

The persistence and moral clarity of Vevcani’s mobilization kick-started the political transition from authoritarianism to pluralism. Thirty years on, international organizations identify government accountability as a top priority for citizens in the Republic of North Macedonia.

Sabotaging the rule of law

Their story offers a broader lesson for the United States.

[Deep knowledge, daily. Sign up for The Conversation’s newsletter.]

For defenders of democracy, it is a reminder of the power of simple, direct questions to expose authoritarianism.

When governments deploy violence against peaceful protesters in the name of law and order, they are the ones sabotaging the rule of law.

And to those tempted to abandon core democratic principles and resort to brute physical force, the Vevcani affair might serve as reminder of what happens to those, like the hardliners of Communist Yugoslavia, who find themselves on the wrong side of history.

Keith Brown's research in the Republic of Macedonia (now the Republic of North Macedonia) was supported by the National Council for Eurasian and East European Research and the Fulbright Program.

Read These Next

Congress once fought to limit a president’s war powers − more than 50 years later, its successors ar

At the tail end of the Vietnam War, Congress engaged in a breathtaking act of legislative assertion,…

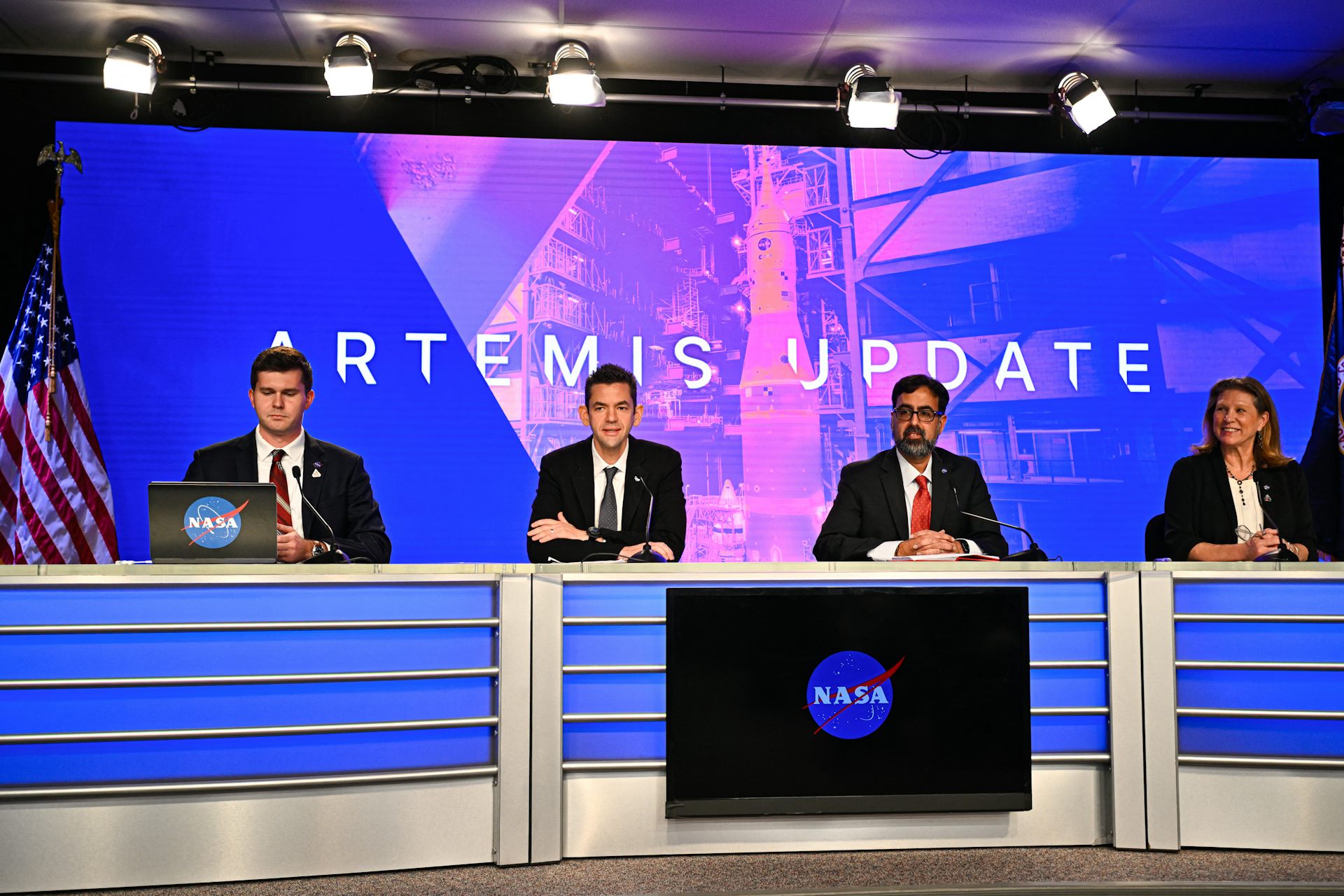

With Artemis II facing delays, NASA announces big structural changes to the lunar program

Artemis II has been plagued by similar issues to those faced by its predecessor, leading NASA to shake…

CIA agents successfully executed a plan for regime change in Iran in 1953 – but Trump hasn’t reveale

A covert US campaign in the mid-20th century helped steer Iran toward the intense anti-American sentiment…