National parks – even Mount Rushmore – show that there's more than one kind of patriotism

President Trump is scheduled to appear at an Independence Day celebration at Mount Rushmore on July 3. For some, this event will symbolize love of country. Others will see it very differently.

July 4th will be quieter than usual this year, thanks to COVID-19. Many U.S. cities are canceling fireworks displays to avoid drawing large crowds that could promote the spread of coronavirus.

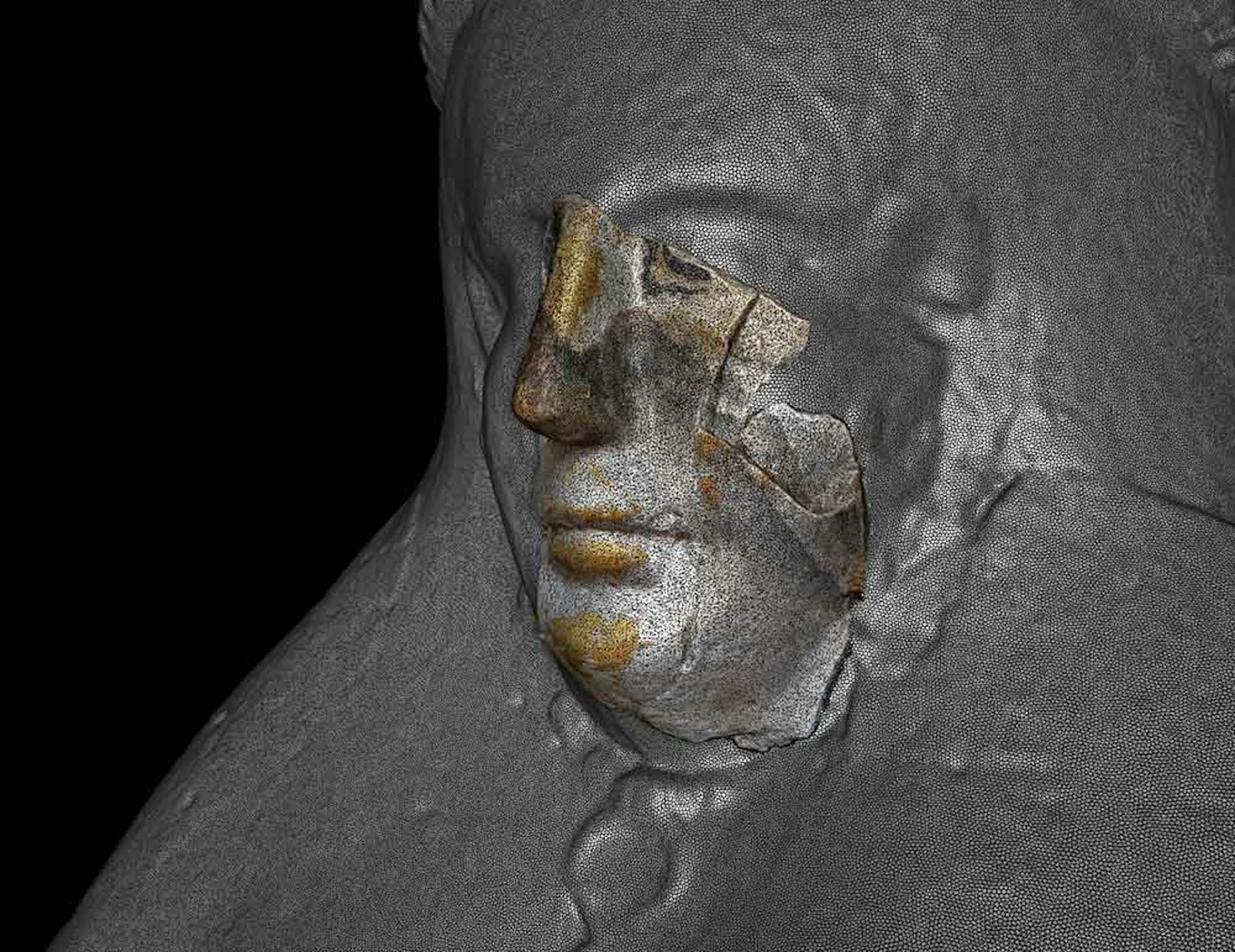

But President Trump is planning to stage a celebration at Mount Rushmore National Memorial in South Dakota on July 3. It’s easy to see why an Independence Day event at a national memorial featuring the carved faces of George Washington, Thomas Jefferson, Abraham Lincoln and Theodore Roosevelt would seem like a straightforward patriotic statement.

But there’s controversy. Trump’s visit will be capped by fireworks for the first time in a decade, notwithstanding worries that pyrotechnics could ignite wildfires. And Native Americans are planning protests, adding Mount Rushmore to the list of monuments around the world that critics see as commemorating histories of racism, slavery and genocide and reinforcing white supremacy.

As I show in my book, “Memorials Matter: Emotion, Environment, and Public Memory at American Historical Sites,” many venerated historical sites tell complicated stories. Even Mount Rushmore, which was designed explicitly to evoke national pride, can be a source of anger or shame rather than patriotic feeling.

Twenty-first-century patriotism is a touchy subject, increasingly claimed by America’s conservative right. National Park Service sites like Mount Rushmore are public lands, meant to be appreciated by everyone, but they raise crucial questions about history, unity and love of country, especially during this election year.

For me, and I suspect for many tourists, national memorials and monuments elicit conflicting feelings. There’s pride in our nation’s achievements, but also guilt, regret or anger over the costs of progress and the injustices that still exist. Patriotism, especially at sites of shame, can be unsettling – and I see this as a good thing. In my view, honestly confronting the darker parts of U.S. history as well as its best moments is vital for tourism, for patriotism and for the nation.

Whose history?

Patriotism has roots in the Latin “patriotia,” meaning “fellow countryman.” It’s common to feel patriotic pride in U.S. technological achievements or military strength. But Americans also glory in the diversity and beauty of our natural landscapes. That kind of patriotism, I think, has the potential to be more inclusive, less divisive and more socially and environmentally just.

The physical environment at national memorials can inspire more than one kind of patriotism. At Mount Rushmore, tourists are invited to walk the Avenue of Flags, marvel at the labor required to carve four U.S. presidents’ faces out of granite, and applaud when rangers invite military veterans onstage during visitor programs. Patriotism centers on labor, progress and the “great men” the memorial credits with founding, expanding, preserving and unifying the U.S.

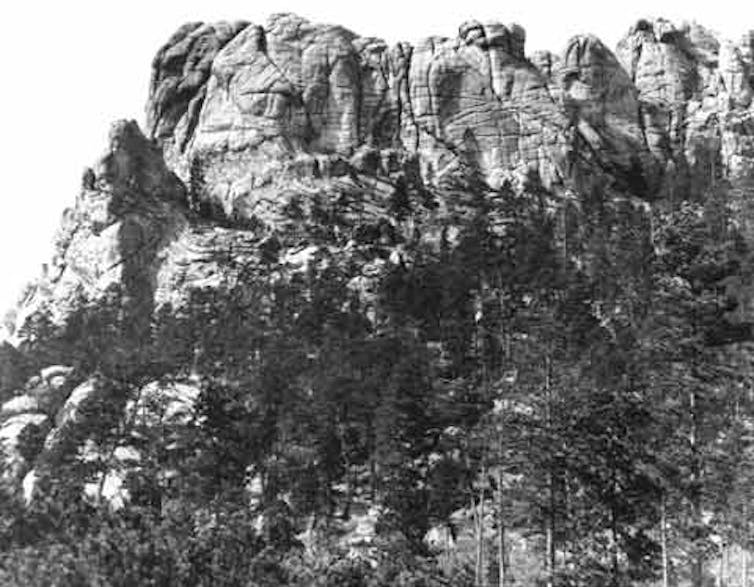

But there are other perspectives. Viewed from the Peter Norbeck Overlook, a short drive from the main site, the presidents’ faces are tiny elements embedded in the expansive Black Hills region.

Re-seeing the memorial in space and contextualizing it within a longer time scale can spark new emotions. The Black Hills are a sacred place for Lakota peoples that they never willingly relinquished. Viewing Mount Rushmore this way puts those rock faces in a broader ecological, historical and colonial context, and raises questions about history and justice.

Sites of shame

Sites where visitors are meant to feel remorse challenge patriotism more directly. At Manzanar National Historic Site in California – one of 10 camps where over 110,000 Japanese Americans were incarcerated during World War II – natural and textual cues prevent any easy patriotic reflexes.

Reconstructed guard towers and barracks help visitors perceive the experience of being detained. I could imagine Japanese Americans’ shame as I entered claustrophobic buildings and touched the rough straw that filled makeshift mattresses. Many visitors doubtlessly associate mountains with adventure and freedom, but some incarcerees saw the nearby Sierra Nevada as barricades reinforcing the camp’s barbed wire fence.

Rangers play up these emotional tensions on their tours. I saw one ranger position a group of schoolchildren atop what were once latrines, and ask them: “Will it happen again? We don’t know. We hope not. We have to stand up for what is right.” Instead of offering visitors a self-congratulatory sense of being a good citizen, Manzanar leaves them with unsettling questions and mixed feelings.

Visitors to incarceration camps today might make connections to the U.S.-Mexico border, where detention centers corral people in unhealthy conditions, sometimes separating children from parents. Sites like Manzanar ask us to rethink who “counts” as an American and what unites us as human beings.

Visiting and writing about these and other sites made me consider what it would take to disassociate patriotism from “America first”-style nationalism and recast it as collective pride in the United States’ diverse landscapes and peoples. Building a more inclusive patriotism means celebrating freedom in all forms – such as making Juneteenth a federal holiday – and commemorating the tragedies of our past in ways that promote justice in the present.

Humble patriotism

This July 4th invites contemplation of what holds us together as a nation during a time of reckoning. I believe Americans should be willing to imagine how a public memorial could be offensive or traumatic. The National Park Service website claims that Mount Rushmore preserves a “rich heritage we all share,” but what happens when that heritage feels like hatred to some people?

Growing momentum for removing statues of Confederate generals and other historical figures now understood to be racist, including the statue of Theodore Roosevelt in the front of New York City’s Museum of Natural History, tests the limits of national coherence. Understanding this momentum is not an issue of political correctness – it’s a matter of compassion.

Greater clarity about value systems could help unite Americans across party lines. Psychologists have found striking differences between the moral frameworks that shape liberals’ and conservatives’ views. Conservatives generally prioritize purity, sanctity and loyalty, while liberals tend to value justice in the form of concerns about fairness and harm. In my view, patriotism could function as an emotional bridge between these moral foundations.

My research suggests that visits to memorial sites are helpful for recognizing our interdependence with each other, as inhabitants of a common country. Places like Mount Rushmore are part of our collective past that raise important questions about what unites us today. I believe it’s our responsibility to approach these places, and each other, with both pride and humility.

This is an updated version of an article originally published on June 26, 2019.

Jennifer Ladino received funding from the National Endowment for the Humanities to support her book on national memorials.

Read These Next

Revisiting the story of Clementine Barnabet, a Black woman blamed for serial murders in the Jim Crow

In 1912, a young Black woman’s supposed religious beliefs were quickly blamed to make sense of a terrifying…

3 generations of Black Philadelphia students report persistent anti-Black attitudes in schools

A sociologist explains how Black students in Philadelphia navigate racial prejudice and find affirmation…

Warming winters are disrupting the hidden world of fungi – the result can shift mountain grasslands

Over a three-decade experiment in the Rocky Mountains, fungi and plant life fundamentally changed. The…