Dead white men get their say in court as Virginia tries to remove Robert E. Lee statues

On June 19, a court will decide whether Virginia must obey a 1890 deed that gave the state a plot of prime Richmond land as long as it would 'faithfully guard' the Robert E. Lee statue erected there.

The latest chapter in the United States’ ongoing debate about Confederate monuments involves some unexpected opinions: those of long-dead land donors.

Responding to sustained, nationwide protests over police brutality, Virginia Gov. Ralph Northam on June 4 vowed to dismantle a prominent statue of the Virginia-born Confederate General Robert E. Lee in Richmond, the state capital.

That plan was put on pause just four days later when a state judge issued an injunction based on the petition of a man whose ancestor, Otway Allen, gave Virginia the land the the sculpture sits on.

In his petition to the court, William C. Gregory claimed that removal of the statue would violate the conditions of his great-grandfather’s 1890 land deed, which says Virginia “will hold said Statue and pedestal and Circle of ground perpetually sacred to the Monumental purpose … and that she will faithfully guard it and affectionately protect it.”

On June 19, a judge will decide whether to let the 10-day injunction expire, enabling Richmond to dismantle its Lee monument, or to obey the donor’s wishes – at least temporarily.

Richmond isn’t the only Virginia city where a centuries-old land deed is a legal hurdle in removing Confederate monuments many see as a symbol of white supremacy. Nearby Charlottesville has faced similar questions about the intentions of the philanthropist who donated its controversial Robert E. Lee statue.

‘Irreparable harm’

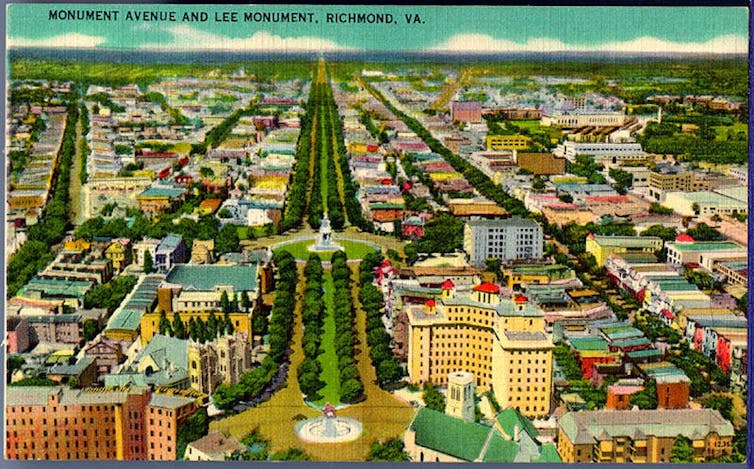

Richmond’s Lee sculpture sits atop a pedestal on a traffic circle at the gateway to Monument Avenue, an architectural paean to white Richmonders’ long tradition of gracious, segregated living.

The land was a gift to the state from real estate investor Otway S. Allen and his sisters, Bettie F. Allen Gregory and Martha Allen Wilson. The donors hoped that putting the monument on the tree-lined boulevard would hasten development of the prestigious, whites-only residential neighborhood planned for the area.

Back in the 19th century, the Lee monument was on the outskirts of the city. Over the next 40 years, four more Confederate monuments were erected along the avenue, which traverses what is now central Richmond.

In his injunction request, Gregory claimed that removing the statue would cause “irreparable harm” because his family “has taken pride for 130 years in this statue resting upon land belonging to his family.”

To many locals, especially black Richmond residents, the sculptures have always been colossal reminders of the South’s history of enslavement and the violence wrought on black lives. The governor and city leaders now seemingly agree, saying that monuments glorifying the region’s white supremacist history should not displayed on public land.

Nevertheless, the Lee statue still has its defenders in Richmond. On June 15, six Monument Avenue homeowners filed their own separate lawsuit to block its removal, claiming that dismantling the “priceless work of art” would lead to the “degradation of the internationally recognized avenue on which they reside.”

Charlottesville’s ‘princely giver’

An hour away in Charlottesville, another Robert E. Lee statue has been embroiled in legal challenges since 2017, when a city council vote for its removal triggered a deadly white supremacist rally.

Charlottesville’s statue was a gift of a prominent local philanthropist, Paul Goodloe McIntire. McIntire, born during the Civil War, was the son of the Charlottesville’s mayor when the city surrendered to General Custer’s Union troops in 1865.

McIntire made his money on the stock exchanges in Chicago and New York before returning to Charlottesville, a city shaped by his philanthropy. Funding Charlottesville’s first library and building an amphitheater for the University of Virginia, McIntire earned the sobriquet “princely giver” of gifts.

In 1918 McIntire donated land to the city for use as a public park, to be called Lee Park. The deed stipulated that a sculpture of the Confederate general, commissioned and paid for by McIntire, would be installed and maintained.

Among other objections to the statue’s removal, the Sons of Confederate Veterans, the Monument Fund and a small group of local citizens cited this land deed in their successful March 2017 legal complaint. They claimed that removing the statue would violate the terms and conditions of McIntire’s gift.

Courts side with progress

Both Virginia lawsuits argue that the land donors’ original wishes are inviolable.

But my legal research on charitable gifts shows that donor wishes are not always set in stone, so to speak. Under state law, Virginia’s included, courts can modify gift conditions when fulfilling them is no longer possible or practicable.

Gifts with problematic racial restrictions and segregationist intentions have troubled many American institutions, from nursing homes established by donors to benefit elderly, white Presbyterians to church scholarships mandated to fund white students only.

In such cases, judges have declined to preserve the outdated wishes of long-dead donors. Instead, they’ve allowed discriminatory gift conditions to be eliminated, rendering the gifts usable in the modern era.

Rice University, for example, was founded in 1912 with a charitable bequest on the condition that the school educate only “the white inhabitants of Houston, and the state of Texas.” In 1963, seeking to integrate the university, Rice trustees filed a motion to modify the racial restrictions.

Despite opposition by a group of alumni who sought to keep the school segregated, the court concluded that strict adherence to the donor’s racial restrictions was no longer practicable and that the terms of Rice’s charter could be modified to admit black students.

Now, a Richmond court must tackle a similar issue. The ruling will determine whether land given to Richmond by a private citizen making a very public statement about the South’s legacy of racial inequality can be used to celebrate new and different histories.

What happens in this former capital of the Confederacy may influence similar cases in Charlottesville and beyond.

[You’re too busy to read everything. We get it. That’s why we’ve got a weekly newsletter. Sign up for good Sunday reading. ]

Allison Anna Tait does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organization that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

Read These Next

What James Madison can teach Americans about religious freedom today

For Madison, religious freedom was not a tool for political domination. Rather, he saw it as a constitutional…

Why do mountaintops stay snowy, even though they’re closer to the Sun?

The answer has to do with the air we breathe and that bright white snowpack, as an atmospheric scientist…

Abandoned Pennsylvania mines and waste-heat recycling could make the state’s massive new data center

In Pennsylvania, new data centers could require enough electricity to power 11 million homes.