Venezuelan migrants face crime, conflict and coronavirus at Colombia’s closed border

The coronavirus-related closure of the Colombian border hasn't stopped desperate Venezuelans from entering – but it has made the trip more dangerous.

Millions of Venezuelans fleeing their crisis-ridden country already had plenty to worry about on their journeys, from food to transport and shelter. Crime is also rampant along the border between Venezuela and neighboring Colombia, the destination for many migrants seeking a better life.

Now there’s a pandemic, too – and its consequences for Venezuelan migrants go beyond health concerns.

Criminal groups that operate in the border zones are capitalizing on the closure of all seven official border crossings to smuggle migrants in and out of Colombia illegally, extort this poor and vulnerable population and recruit new members.

Risks to migrants and refugees

Oil-rich Venezuela used to have one of Latin America’s most robust economies, but its fortunes have declined massively since the death of president Hugo Chávez in 2013.

His successor, Nicolás Maduro, left with a steeply unbalanced budget and dropping oil prices, has led the South American country into the abyss. By 2019, hyperinflation in Venezuela had reached 10,000,000%, and 9 out of 10 Venezuelans lived in poverty.

To date, 5 million people have fled persecution, poverty and political turmoil in Venezuela – a mass migration rivaling that of war-torn Syria. Around 1.8 million of them settled in Colombia.

We have been monitoring this migratory crisis for years as part of our extensive research on the overlapping humanitarian and security crises in Colombia’s borderlands.

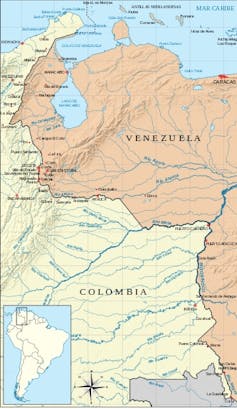

Before the pandemic, up to 40,000 Venezuelans were crossing the porous 1,378-mile Colombia-Venezuela border daily. Most of them remained in the country for a short period of time before passing onto other countries or returned to Venezuela that day after buying food, medicine and other items that are extremely scarce in Venezuela. Goods purchased in Colombia and resold across the border are one way Venezuelans survive, and a major source of income for border-area residents.

But, typically, about 2,000 Venezuelans would end up staying for good in Colombia each day, according to Christian Krüger, former director of Migración Colombia, Colombia’s customs agency.

Despite efforts by international aid groups, the United Nations Refugee Agency and the Colombian government to assist the migrants, the situation along the border was “overwhelming,” a Bogotá official told us in February.

Xenophobia, violence and victimization

The border’s closure on March 14 due to the COVID-19 outbreak has only made a bad situation worse, our research finds.

Transit across the border is now permitted essentially only for Venezuelans leaving Colombia – not the thousands still clamoring to get in to buy urgently needed food and medicine.

But no government is entirely in charge of what happens at the Colombia-Venezuela border, which is nearly as long as the U.S.-Mexico border and runs through desert, dense jungles and the towering Andes mountains.

An array of rebels, criminals and corrupt officials control informal border crossings, where they sneak Venezuelans into Colombia in exchange for “taxes” or forced sex. Human trafficking groups also prowl the region looking for potential victims, especially children, who are sold into prostitution.

Venezuelans arriving further south in Colombia, to the Arauca region, may also be targeted for recruitment by insurgent groups like the National Liberation Army, Colombia’s largest active rebel group.

The recent arrival of U.S. military troops in the border region, officially to support Colombian anti-drug efforts, adds to the tense climate. And, our research shows, the militarization of the border further increases the risks for vulnerable people on the move.

Meanwhile, in the deserts of La Guajira, hundreds of homeless Venezuelan migrants are sleeping on the streets. This makes them extremely vulnerable not only to the coronavirus, a humanitarian worker in the region told us, but also to violent assault and harassment by criminal groups and youth gangs.

Colombia is one of the many countries where criminals have been indirectly empowered by COVID-19 lockdowns.

Some armed groups are imposing curfews to enforce quarantines and bringing in nurses to care for the sick in slum areas, strengthening their power over residents as a kind of shadow government. Other criminal organizations are using the climate of uncertainty to intimidate, displace or kill those who do not comply with their own arbitrarily defined “public health rules.”

Our past studies on civilian behavior in such contested territory have found that Venezuelans who have only recently arrived in Colombia are particularly subject to harassment and exploitation because they don’t know the rules of the game.

Return migration

Lacking shelter, safety, health care and jobs in Colombia as the coronavirus surges, many Venezuelans have been driven to despair and have returned home. By late May, over 68,000 Venezuelans had returned to their country.

Theirs is usually not a happy, or lasting, return.

Some Venezuelan migrants come back with COVID-19, a Venezuelan primary teacher in the border state of Zulia told us. Her school, like many others in the area, now shelters newly returned migrants for 14 days, in accordance with Venezuelan government rules.

The return migrants receive some assistance from local humanitarian organizations and the regional government – but not enough. And the sick are unlikely to get treatment or aid in crisis-stricken Venezuela.

With the “regular” black market of Colombian products smuggled into Venezuela disrupted, a local social worker in the border regions explained to us, people are desperate for medicine and food.

As we learned from a U.N. official working with migrants in the region, a recent U.N. survey found that 70% of Venezuelans who left Colombia because of the pandemic hope to return once the situation improves.

The prospects for this are uncertain, to say the least.

[You need to understand the coronavirus pandemic, and we can help. Read The Conversation’s newsletter.]

Annette Idler receives funding from Global Affairs Canada. She also receives funding from the UK Arts & Humanities Research Council and the Economic & Social Research Council through the Partnership for Conflict, Crime & Security Research.

Markus Hochmüller receives funding from Global Affairs Canada.

Read These Next

China’s muted response over war in Iran reflects Beijing’s delicate calculus as a concerned onlooker

Beijing has denounced US-Israeli action in Iran, but has not rushed to come to the aid of its regional…

Venezuela’s fragile forests face rising risks as US pushes for oil and critical minerals and illegal

The Orinoco Basin is one of the most biodiverse places on the planet. It’s also rich in oil, gold…

Today’s obsession with authenticity isn’t new – being true to yourself has troubled philosophers for

Contemporary culture seems obsessed with authenticity – but the question of how to be ‘sincere’…