Leaders' empathy matters in the midst of a pandemic

Leaders who exude empathy in the midst of the COVID-19 crisis are experiencing surges in popularity. President Donald Trump's apparent lack of empathy is becoming a campaign issue.

Resilience, communication skills, openness and impulse control top the list of six qualities that presidential historian Doris Kearns Goodwin says are common to good leaders.

In her book “Leadership: In Turbulent Times,” Goodwin surveyed the lives and leadership styles of four American presidents – Abraham Lincoln, Theodore Roosevelt, Franklin Delano Roosevelt and Lyndon B. Johnson – in an effort to distill what characterized them.

Another of the leadership traits Goodwin lists turns out to be of great value during these pandemic days: empathy.

The leaders who exude empathy in the midst of the COVID-19 crisis are experiencing surges in popularity. The New York Times has called Gov. Andrew Cuomo of New York “the politician of the moment,” noting, among other things, his briefings, which now regularly reach national audiences and are “articulate, consistent and often tinged with empathy.”

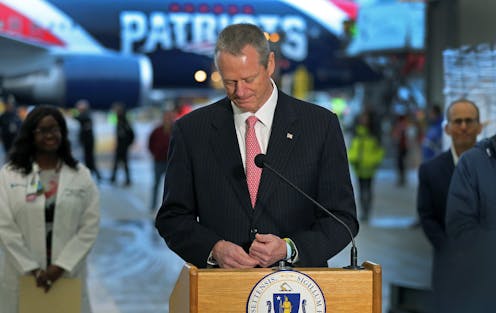

Even Massachusetts Gov. Charlie Baker, who is known for his businesslike demeanor, has shed tears during press briefings several times in recent weeks. When he recently recounted how his best friend lost his mother to the disease, he choked up.

“I pay attention to the numbers but what I really think about mostly are the stories and the people who are behind the stories,” Baker said.

This experience, Baker added, caused him to think about “the importance of loved ones putting it all out there and making sure they don’t leave anything unsaid,” confiding that with his own father, “I try to say more.”

Empathy contagion

In my ethics courses, as well as in my scholarship, I emphasize the importance of empathy in moral decision-making.

Michael Slote, a moral philosopher and author of several books on the resurgent 18th-century movement known as moral sentimentalism, writes, “empathy involves having the feelings of another (involuntarily) aroused in ourselves, as when we see another in pain.” This he likens to an infusion or, more appropriate to our current moment, a contagion of “feeling(s) from one person to another.”

Nell Noddings, one of the foundational voices of the Ethics of Care, an ethical theory that highlights the importance of empathy, writes that when one empathizes with another, the person doing the empathizing becomes a “duality,” carrying the other’s feelings along with their own.

The nonempathist

President Donald Trump is not known for his empathy. Nearly every evening as the president addressed the nation through his televised briefings, he has had the opportunity to show he “feels your pain,” to quote one of Trump’s predecessors, Bill Clinton.

But this president can’t seem to overcome what CNN’s chief political analyst Gloria Borger calls his “empathy gap.”

“Empathy has never been considered one of Mr. Trump’s political assets,” writes Peter Baker, chief White House correspondent for The New York Times. Indeed, at his briefings, Trump shows “more emotion when grieving his lost economic record than his lost constituents,” Baker writes. At best, Trump seems to be able to muster something more akin to sympathy.

But sympathy is not the same as empathy. Sympathy feels bad for others. Empathy feels bad with others. Sympathy sees what you’re going through and acknowledges that it must be tough. Empathy attempts to go through it with you.

Trump has done little more than acknowledge suffering, as he did last month when he refused to condemn protesters rallying against COVID-19 restrictions, instead saying “they’ve been going through it a long time … and it’s been a tough process for people … There’s death and there’s problems in staying at home too … they’re suffering.”

Leverage with voters?

Now it looks like Trump’s apparent lack of empathy is being used as an election issue by Democratic party leaders.

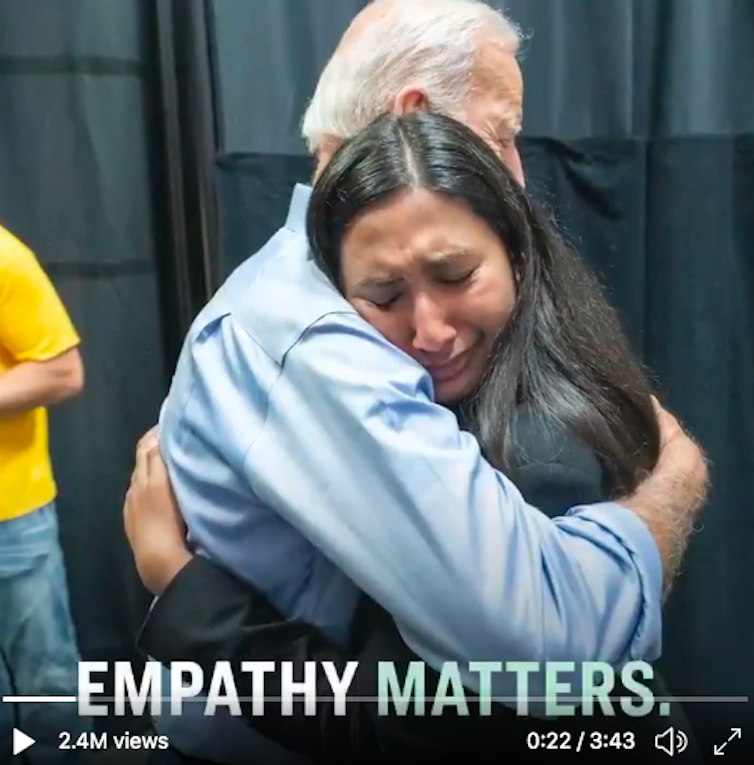

In a recent town hall, presumptive Democratic presidential nominee Joe Biden pointed directly to Trump’s behavior as a crucial failing: “Have you heard him offer anything that approaches a sincere expression of empathy for the people who are hurting?”

By way of contrast, as endorsements begin to pile up for Biden, empathy is on the tip of his supporters’ tongues. In his endorsement of his former second-in-command, President Barack Obama praised Biden’s “empathy and grace.” Tom Perez, chairman of the Democratic National Convention, noted that the tragedies that Biden has experienced in his own life, including the 1972 death of his first wife and 13-month-old daughter in a car accident and, more recently in 2015, his son’s death from brain cancer, “have given him the empathy to lead us forward.”

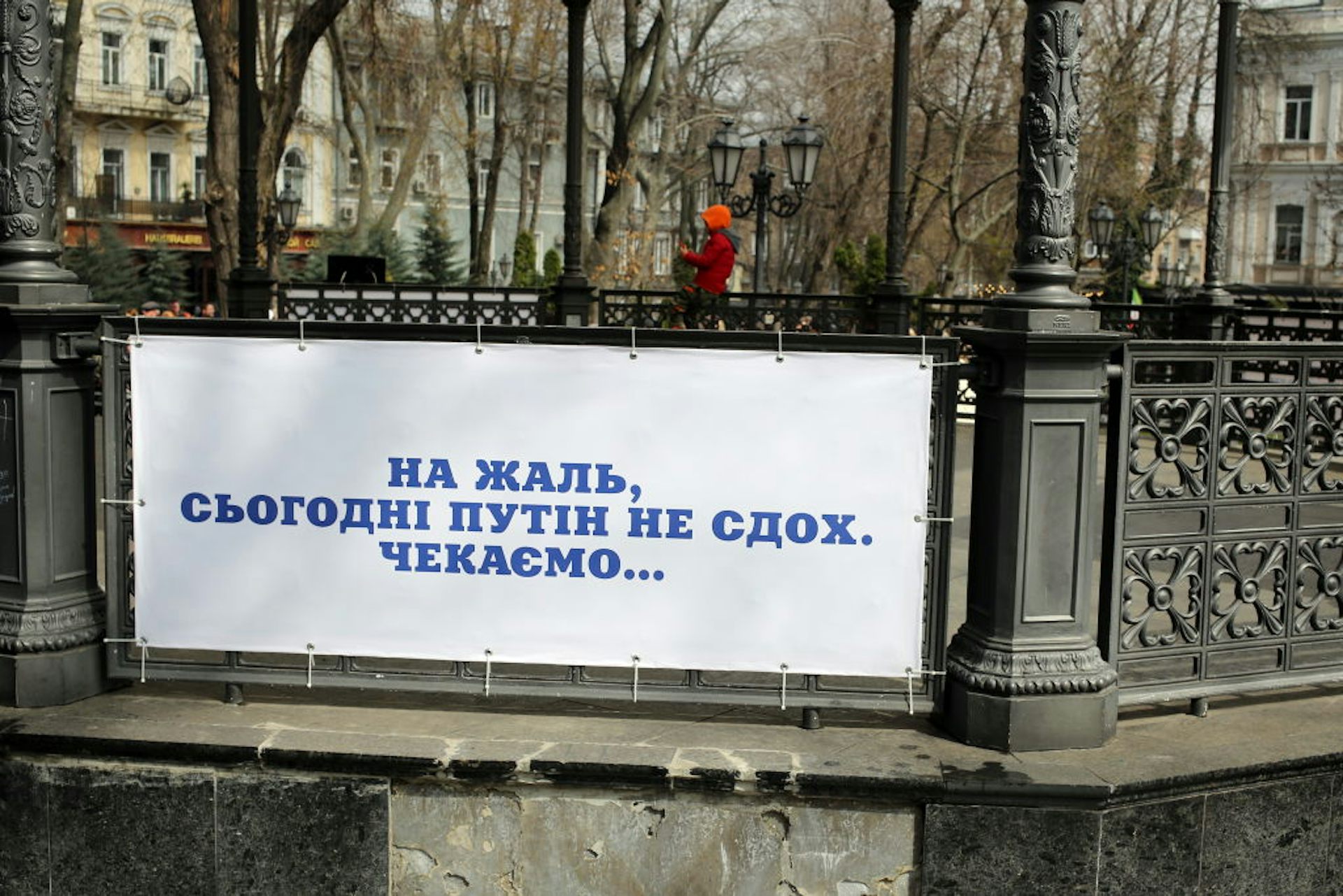

And, in her endorsement of Biden, former rival Elizabeth Warren highlighted the way his experiences “animate the empathy he extends to Americans who are struggling.” She goes on to state unequivocally, “Empathy matters.”

Effective leaders empathize

While there is no definitive list of qualities that all great leaders must possess, Doris Kearns Goodwin writes, “we can detect a certain family resemblance of leadership traits” through history.

Empathy has played a pivotal role in American history when presidents feel with, and act in response to, their constituents’ needs. Indeed, leaders who empathize, who relate to and feel with their people can ask them to do difficult things.

That aptly describes New Zealand’s Prime Minister Jacinda Ardern, who was recently profiled in The Atlantic magazine. The article’s headline, perhaps hyperbolically, suggests that because of her ability to empathize, Ardern may be “the most effective leader on the planet.” One of Ardern’s forerunners sums it up: “There’s a high level of trust and confidence in her because of that empathy.”

And empathy works; the trust that New Zealanders have placed in Ardern, along with her government’s strong measures to stem COVID-19, are both credited with dramatically reducing the outbreak’s severity in her country.

It is easier to trust an empathetic leader; their empathy is better assurance than the weak sympathy of a leader who grieves the loss of his own power over the loss of life.

It turns out, most of us just can’t empathize with a person like that.

[You need to understand the coronavirus pandemic, and we can help. Read The Conversation’s newsletter.]

Jonathan D. Fitzgerald does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organization that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

Read These Next

Hezbollah − degraded, weakened but not yet disarmed − destabilizes Lebanon once again

Hezbollah’s entry into the current war followed the killing of Ayatollah Ali Khamenei. The group has…

Congress once fought to limit a president’s war powers − more than 50 years later, its successors ar

At the tail end of the Vietnam War, Congress engaged in a breathtaking act of legislative assertion,…

Housing First helps people find permanent homes in Detroit − but HUD plans to divert funds to short-

Detroit’s homelessness response system could lose millions of dollars in federal funding for permanent…