Why prisoners are at higher risk for the coronavirus: 5 questions answered

Half of incarcerated individuals have either a chronic medical or a mental health condition. But social distancing and rigorous hygiene are unattainable for many US jails and prisons.

COVID-19 has created a new norm for human interaction: social distancing, improving hygiene with soap and hand sanitizer, wearing a mask and quarantining.

But what does this mean for the more than 2 million people held in local, state and federal jails and prisons?

As a criminal justice scholar who has written about incarcerated populations, I have some concerns about the risks for people who are incarcerated.

1. Why are incarcerated people at higher risk of COVID-19?

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention says there is a higher risk of severe complications from COVID-19 for the elderly and those with chronic health conditions, such as asthma, diabetes and high blood pressure.

According to the CDC, extra precautions should be taken for citizens with disabilities. This is especially true for those with communication, mental health and mobility issues, as they may face challenges with social distancing and are less likely to seek medical care when needed.

As indicated in my book, “Aging in Prison,” these health concerns are magnified within incarcerated settings.

Prisoners have often experienced poor health and limited access to health care before incarceration. Once incarcerated, prisoners often age prematurely, experiencing health problems associated with people in the general population who are 10 to 15 years older. Their experiences in jail and prison can cause psychological distress and the manifestation of mental illnesses.

Consequently, half of prisoners have either a chronic medical or a mental health condition. That means that the incarcerated population is at heightened risk for developing severe complications from COVID-19.

Despite the CDC’s awareness of challenges behind bars, the agency recommends similar protocols for incarcerated people as for the general public, including social distancing and “enhanced cleaning/disinfecting and hygiene practices.”

2. But is social distancing a solution for the incarcerated?

Social distancing means staying at least 6 feet from other people, not gathering in groups, and staying out of crowded places.

This is impractical for incarcerated populations, who reside in institutions where prisoners live, work, eat, sleep and even bathe in communal settings.

Jails and prisons are often overcrowded and have inmates and staff coming and going. The daily routine creates an environment ripe for the spread of infectious diseases.

The risk of transmission remains high. Social distancing, in the words of one governor, is challenging.

On April 8, The New York Times reported more than 1,324 cases connected to prisons and jails, with the Cook County Jail in Chicago, reporting 238 inmates and 115 staff. As of five days later, 306 inmates and 218 staff had tested positive.

3. Why not have prisoners use better hygiene or wear face masks?

Jails and prisons do not operate like our homes or our workplaces.

Many correctional facilities restrict access to common hygiene products containing contraband ingredients, such as alcohol-based hand sanitizer. While the incarcerated may have access to water, there’s no guarantee that they will be able to access soap and dry their hands at the same time.

Moreover, it’s hard to disinfect surfaces in your cell, the bathroom, the cafeteria or elsewhere in prison when you have limited access to products with alcohol or soap.

Should an incarcerated person become ill, toilet paper and tissues may not be readily available. Poor ventilation in many facilities means the spread of an airborne virus is often quick and deadly.

These are some of the same factors linked to the spread of tuberculosis in prison.

4. What about health care for the incarcerated?

Members of the general public who exhibit COVID-19 symptoms – fever, cough, tiredness and difficulty breathing – are encouraged to speak with their doctor and get tested.

Behind bars, there is a shortage of health care professionals and a long history of denial of access to adequate medical care for chronic conditions and diseases.

Many facilities charge inmates a copay for treatment that incarcerated people are ill-equipped to afford. Most jails and prisons do not have medical isolation units for those who are ill.

Stories are coming from multiple facilities about the lack of access to medical care for testing and treatment of COVID-19 symptoms and the consequences of seeking treatment. In one case, an inmate did not receive medical care until he passed out. In New York, inmates stated that correctional officers refused to take symptomatic inmates to medical for treatment.

Prisoners have started fights, engaged in hunger strikes and threatened to start fires in facilities when they learned about positive tests.

5. What’s to be done?

As it stands now, there will likely be a significantly higher prisoner mortality rate compared to the general public – not just for those sentenced to a period of incarceration in prison, but also those who are sitting in local jails who have yet to be convicted or sentenced.

The police in some locations have decided not to arrest, but instead issue citations for a variety of offenses that just a few months ago would have landed the person in the local jail.

The Federal Bureau of Prisons, parole board members and other advocates from across the country now call for the early release of incarcerated individuals who pose less risk of harm to society, including the elderly, nonviolent and low-risk prisoners, and those with severe medical conditions.

As jails and prisons release the incarcerated early, government officials should give greater attention to the process of release. Without a plan for the release of prisoners coming from highly infected institutions, who were exposed but not tested, there is the danger of spreading the virus to the local general population.

At the same time, the formerly incarcerated will need more than the typical support provided upon release. Relatives may be less likely to take them in, resulting in homelessness. That’s why California and New York have put released prisoners up in hotels. Self-isolation means there are no jobs. And, of course, because of where they are coming from, there is an increased possibility of testing positive after release.

[Get facts about coronavirus and the latest research. Sign up for The Conversation’s newsletter.]

Martha Hurley does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organization that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

Read These Next

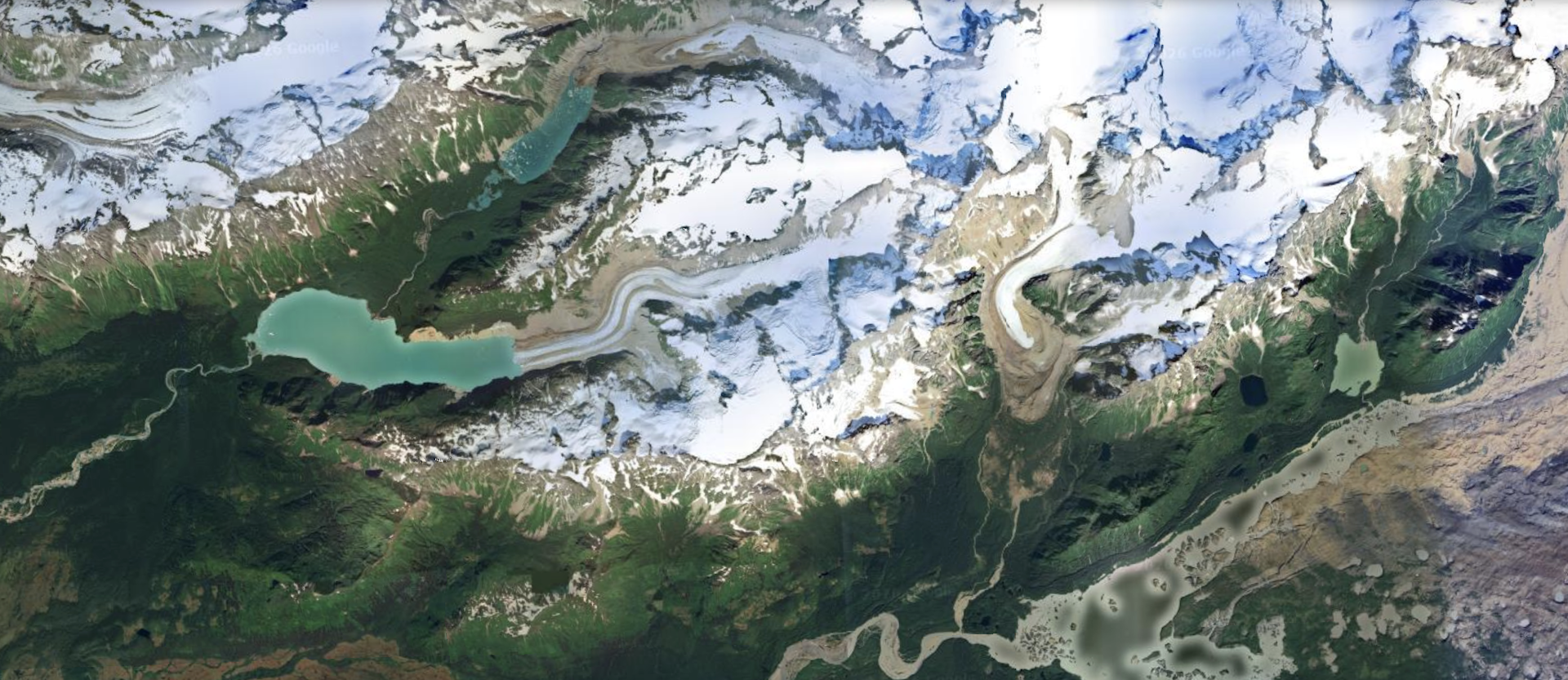

Alaska’s glacial lakes are expanding, increasing the risk of destructive outburst floods

Scientists mapped the evolution of 140 glacial lakes in Alaska and found a way to tell how much larger…

US is less prone to oil price shocks than in past decades

Oil prices affect the US economy differently than in past decades. Nowadays, the US is less reliant…

Mobile clinics offer a practical way to improve health care access in maternity care deserts

Mobile health clinics are a practical but underused solution to the growing number of maternity care…