Domestic violence growing in wake of coronavirus outbreak

What would you do if you weren't safe at home – and now you're not allowed to leave because of the coronavirus pandemic?

As people across the country scrambled to buy toilet paper and extra canned food, millions of them had an additional set of stresses: worrying about being forced to stay at home, unable to get away from their abuser.

Consider these possibilities:

- Millions of Americans are not safe from violent abuse at home. Now the federal, state and local governments are telling everyone to stay there – for their own safety.

- For some people, going to work may be their only reprieve from emotional abuse and violence. Now they have been told to work from home.

- For others, the only place their children are safe from abuse is at school. Now those children have been told to study at home.

- If a person suffering abuse is planning to leave, they may be secretly stashing money away to make an escape. Now they may need that money for other expenses, because few jobs are completely safe from the economic fallout of the coronavirus crisis.

What would you do if the only opportunity you had to seek help or look online to learn how to make a safety plan was when your abuser left for work – and now they’re never leaving the house?

These are the kinds of problems that, as the nation locks down, have me and my fellow domestic violence researchers worried about millions of Americans.

A rising threat

Even before the pandemic, an average of 20 people in the United States experienced physical domestic violence every minute. Research shows 1 in 4 adult American women and 1 in 7 adult American men have experienced some type of severe violence – including being hit with something hard, being kicked or beaten, or being burned on purpose – at the hands of an intimate partner.

Disasters – whether hurricanes, earthquakes or pandemics like the coronavirus – disrupt social and physical environments for large groups of people. These changes increase families’ vulnerabilities to domestic violence.

After Hurricane Katrina in 2005, for instance, scholars found a one-third increase in emotional abuse and a near-doubling in physical abuse among women experiencing domestic violence.

In the wake of 2017’s Hurricane Harvey, the Texas Council on Family Violence found that as the storm crisis developed, domestic-violence response organizations received more calls than their normal weekly and monthly average. Specifically, there was an increase in severe violence such as strangulation, kicking, beating, stabbing and other injuries with weapons.

Observers are already seeing a pattern of increasing domestic violence around the world, correlating with the timing of social distancing lockdowns.

Early reports from China show at least a tripling of domestic violence. Cities across Europe and the U.K. are also reporting surges in domestic violence calls.

The United States is seeing a similar pattern. For example, in Seattle, one of the first U.S. cities to have a major outbreak, the police saw a 21% increase in domestic violence reports in March. In Texas, during March the Montgomery County District Attorney saw a 35% increase in domestic violence cases. Police around the country are adapting their domestic violence response plans to prepare for the expected increases and to ensure victims can get help even with restrictions on public movement.

It’s about power and control

Right now, many different factors are combining to cause Americans – and people all around the world – to feel like their lives are not under their control.

Regular routines for work, education, exercise, entertainment and socializing are all disrupted. Millions have lost their jobs or had their hours or pay reduced. People who have existing medical conditions are both more vulnerable and less able to seek treatment.

When people feel powerless in one area of their lives, they often seek to establish more power over other areas. This is particularly dangerous in domestic violence situations, because domestic abuse is, at its core, an effort by one partner to dominate and establish psychological, emotional, physical and sexual control over the other partner.

Since it’s not clear how much time people will need to be in relative isolation or when they will be able to work, socialize and regain control over their own lives, this coronavirus situation may be even more difficult than other disasters and emergencies. This will increase abuse in vulnerable homes that may have been unhealthy but not yet violent, and raise violence levels in already violent homes.

Even the healthiest people have a hard time being isolated for long periods. Many abusers don’t have the emotional resources and coping skills to handle the pressure.

Abusers who are in treatment for domestic violence or otherwise are trying to get a handle on their problems may also have difficulty because their support options – like attending a counseling meeting, seeing or talking with their therapist, or leaving the house to visit with a friend or work out – are more limited now.

Another aspect of the coronavirus pandemic is also worsening the situation: Domestic-violence hotlines are reporting calls from victims whose abusers won’t let them leave the house because they might catch the disease, and are threatening to lock them out if they do leave.

Some solutions emerge

People are aware of the escalating problem: The recent US$2 trillion federal CARES Act included assistance for nonprofits that provide support for domestic violence victims, letting them apply for business loans and help meeting payroll.

Mental-health organizations are issuing suggestions to help families reduce uncertainty and stress in the home.

In France, people who are suffering from domestic violence can get help by going to a pharmacy – businesses that are still open amid the lockdown – and using a code word to ask for assistance. New Zealand motels are offering their vacant rooms as shelters for people who need to leave unsafe homes – without violating social-distancing guidelines.

Average people can help, too, reaching out to loved ones to stay connected, setting up regular check-in times and even agreeing on code words to signal there is a crisis they need help with. This pandemic is challenging, and staying at home can be difficult, but there is help.

Editor’s note: If you or a loved one is experiencing domestic violence, the National Domestic Violence Hotline offers several contact methods: Call 800-799-7233, text LOVEIS to 22522 or visit its website, which has online chat support available around the clock. If you need help with other types of violence or mental health issues, text the Crisis Text Line at 741741.

[Get facts about coronavirus and the latest research. Sign up for The Conversation’s newsletter.]

Shelly Wagers works for the University of South Florida as an Assistant Professor in the Criminology Department http://intra.cbcs.usf.edu/PersonTracker/common/cfm/unsecured/criminology/bio.cfm?ID=990. She is affiliated with the National Partnership to End Interpersonal Violence Across the Lifespan www.npeiv.org, by participating in its annual think tank and serving as its Volunteer Executive Director.

Read These Next

Congress once fought to limit a president’s war powers − more than 50 years later, its successors ar

At the tail end of the Vietnam War, Congress engaged in a breathtaking act of legislative assertion,…

Housing First helps people find permanent homes in Detroit − but HUD plans to divert funds to short-

Detroit’s homelessness response system could lose millions of dollars in federal funding for permanent…

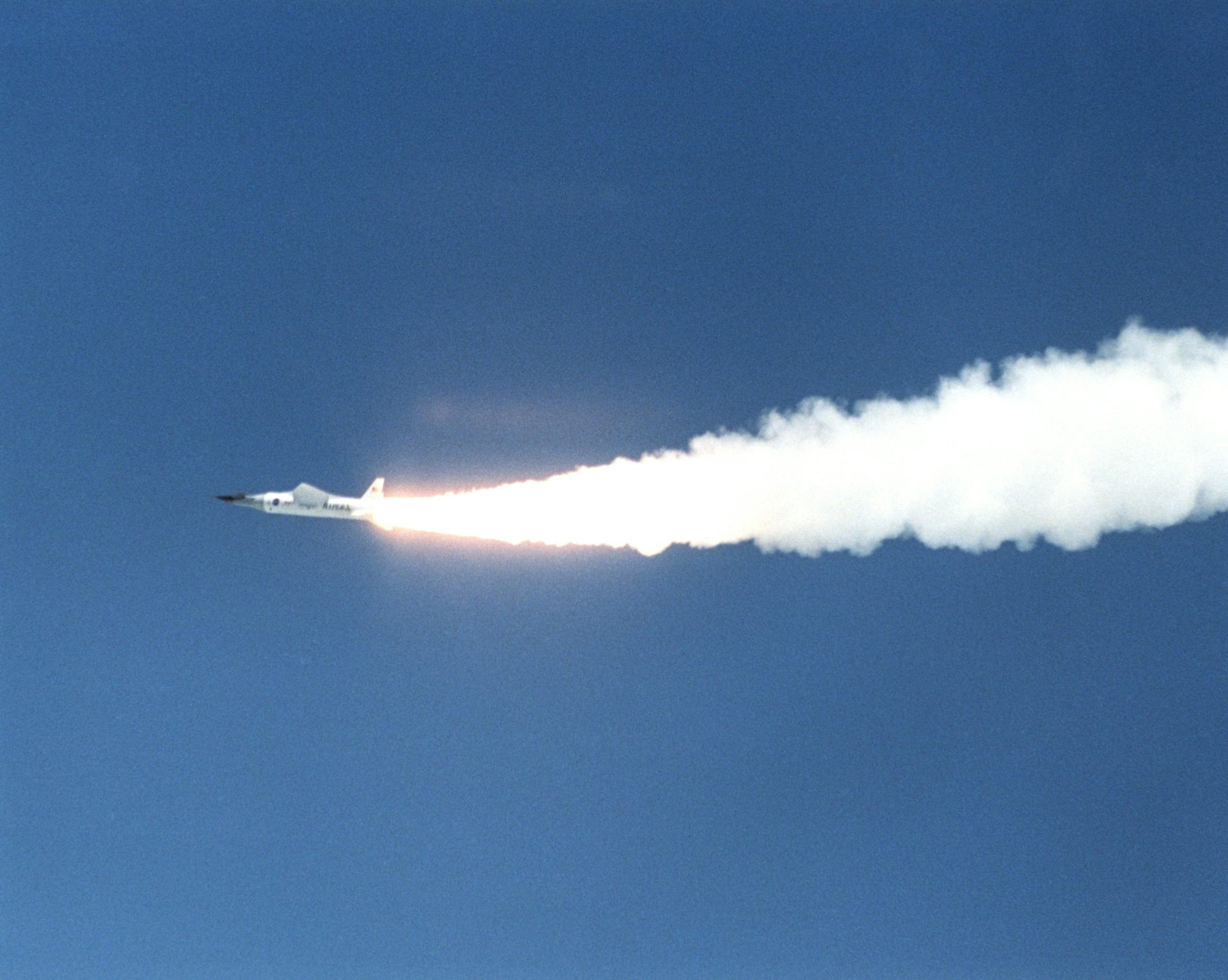

AI and 3D printing help researchers create heat- and pressure-resistant materials for aerospace and

AI models are designing new metal alloys that have been 3D-printed and tested in the lab. The results…