How coronavirus has ended centuries of hands-on campaigning for politicians

Coroanvirus has ended politics as normal. What will campaigning look like without handshaking, high fives and the kissing of babies?

Opening a rally for Bernie Sanders in early March, Rep. Ilhan Omar turned to the audience and asked people to hold hands with those next to them in a show of solidarity.

But that was before the coronavirus disrupted politics as normal. Now the rallies are gone and touching others is strongly discouraged.

American politics is often framed in terms of a simple voting contest. As a historian of the five senses, I understand that the political process involves much more and should include discussions of legitimacy and human interaction, especially through the sense of touch.

Many now accept that a prolonged period of social distancing and self-isolation measures are necessary as America attempts to slow the spread of the virus.

Significant events have nearly all been canceled or postponed. Standard markers of the yearly cycle, like March Madness, spring training and the summer movie season have all been significantly altered.

But the profound effects of the novel coronavirus extend beyond entertainment and socializing. The change in tactile behavior - touch - we are experiencing as a result of the pandemic will greatly alter the function of our democracy.

The tangible distancing necessary to slow or contain the coronavirus is already affecting the country’s political rituals.

States and parties are postponing primaries, the Democratic Party has pushed back its national convention, Congress is debating whether to go remote and political events at the local level are being canceled.

Meanwhile President Trump spends an increasing amount of time dedicated to the crisis and engages in daily briefings which he uses to both deliver updates and disparage critics of his response. And even Trump, a self-proclaimed germaphobe, has lamented the impact coronavirus has had on handshaking.

Coronavirus will greatly alter many aspects of politics during the 2020 election cycle, not least traditions of political touching.

The king’s touch

The use of bodily contact by politicians and leaders – either to convey warmth and trustworthiness or to legitimize claims to rule – has a long history.

In early modern Europe, the tradition of the king’s touch involved sick people being presented to royalty. The king would then place his hands upon the ill person in an attempt to cure the inflicted.

Most of these cases involved the condition of scrofula. Caused by tuberculosis, scrofula produces a large growth on the neck. Often, it clears up on its own and the tumors recede – giving the appearance that the king’s touch was curative.

The message being conveyed was that the monarch had special powers, that divine right – the belief that God provided the king the right to rule – was being displayed through the body of the king, who was able to heal the ill.

The modern tradition of kissing babies and glad-handing with supporters came later but still follows from the idea that those in power have types of charisma – a word that originally meant a divinely conferred power – that can be sensed through touch.

Political touching

As monarchies gave way to elected governments, touching remained a potent way that politicians retained their sense of legitimacy as a man or woman of the people. The handshake became a common way that American politicians, specifically, engaged with voters at a personal level.

Abraham Lincoln was well known for his constant political tours, often to the extent that the frequency of his glad-handing on the trips would make his signature appear shaky on important documents.

The handshake also became a staple of 20th-century party politics, whether in backroom deals or between politicians and their constituencies. The constant images of Bill Clinton shaking hands, patting backs and hugging different supporters on the campaign trail in 1992 increased the sense of interpersonal trust that became so associated with the future president.

When to shake hands – and when not to – has also become subject to occasional political intrigue. On the debate stages of 2016, Trump and his challenger Hillary Clinton appeared to skip with tradition and keep their hands to themselves.

The role of the handshake in legitimizing and conveying trust will fade during this election year.

Turnout fears

And it isn’t just the behavior of politicians that will be affected by the outbreak this electoral cycle.

Coronavirus and its restrictions on touching will change how people turn out to vote. Fears over crowds at polling places and concerns over keeping polling machines, pens and ballots free of the virus will combine to keep people away.

The virus will, no doubt, affect the outcome of elections, as turnout will decrease. In modern American politics, low turnouts usually help conservative candidates. And this new threat may further assist keeping turnout low.

The pandemic may also turn polling into a vote-by-mail exercise. But even that that has been subject to concerns, with Washington state warning voters not to lick envelopes containing their mail-in vote.

Digits going digital

Even with these many changes to political traditions, touch will not be removed from the 2020 election, as the sense will increasingly be felt through the touch of a screen or keyboard at home.

A political world that shifted heavily to message boards and memes during the 2016 election will likely further enter social networks and more anonymous digital spaces.

The loss of touch in standard American politics may further the partisan divide, as individuals isolate from interpersonal human interaction that can often overcome hardened ideologies. Politics as normal may be gone for a while, but the fight over who should hold power will remain.

[Get facts about coronavirus and the latest research. Sign up for The Conversation’s newsletter.]

Andrew Kettler does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organization that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

Read These Next

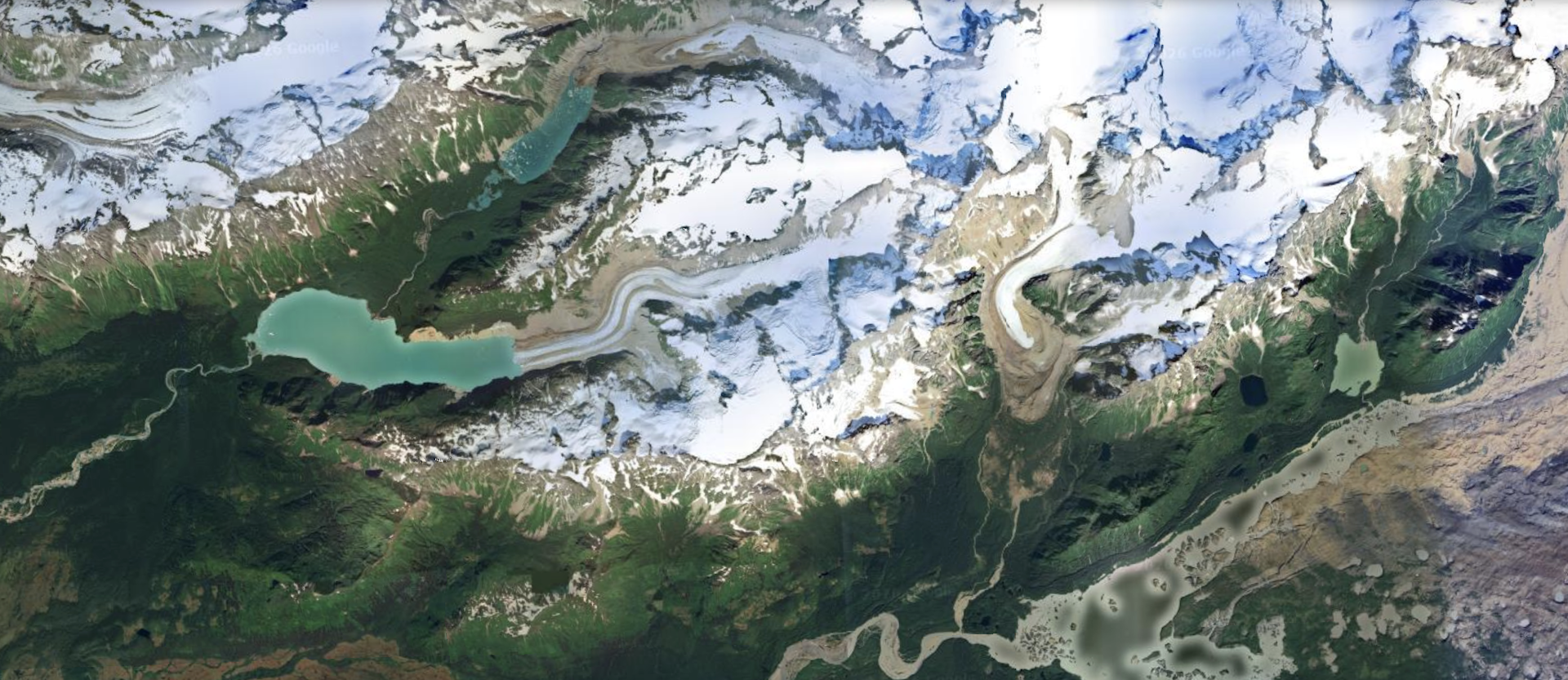

Alaska’s glacial lakes are expanding, increasing the risk of destructive outburst floods

Scientists mapped the evolution of 140 glacial lakes in Alaska and found a way to tell how much larger…

Silicone wristbands can help scientists track people’s exposure to pollutants like ‘forever chemical

From wearable samplers to passive environmental monitoring, new research is changing how scientists…

Arming a Kurdish insurgency would be a risky endeavor – for both the US and Iran’s minority Kurds

Washington has long worked with Kurdish groups in the Middle East. But without sufficient support, encouraging…