Deal with ransomware the way police deal with hostage situations

Police experience in crisis and hostage negotiation could come in handy when dealing with cybercriminals who have, effectively, kidnapped data.

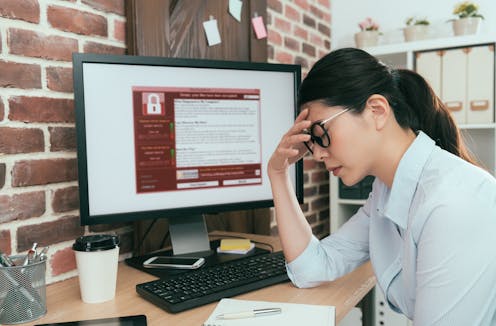

When faced with a ransomware attack, a person or company or government agency finds its digital data encrypted by an unknown person, and then gets a demand for a ransom.

As that type of digital hijacking has become more common in recent years, there have been two major ways people have chosen to respond: pay the ransom, which can be in the hundreds of thousands of dollars, or hire computer security consultants to recover the data independently.

Those approaches are missing another option that we have identified in our cybersecurity policy studies. Police have a long history of successful crisis and hostage negotiation – experience that offers lessons that could be useful for people and organizations facing ransomware attacks.

Understanding the problem

In the first nine months of 2019, more than 600 U.S. government agencies – including entire municipal governments – suffered ransomware attacks. Louisiana Governor John Bel Edwards was forced to declare a state of emergency following ransomware attacks on state government servers that caused widespread network outages at many state agencies, including the Office of Motor Vehicles and the departments of Public Health and Public Safety.

Many of those victims chose to pay the ransom demanded by whoever hijacked their data. Lake City, Florida, for instance, paid US$460,000 to unlock its data.

Other targets, like the city of Baltimore, chose to fight back instead of paying the ransom. Rather than handing the attackers the $76,000 they demanded, Baltimore paid more than $10 million to purchase new equipment and absorbed more than $8 million in lost revenue from taxes and fees that went unpaid while systems were down.

Those moves were in line with FBI advice saying that paying the ransom could increase the likelihood of additional attacks, both on previous targets and new ones.

More recently, the FBI has softened its stance to open the door to the paying of ransom in certain cases, but to always report doing so to law enforcement. Although the agency still underscores that paying a ransom does not guarantee that the encrypted files will be recovered, or that the victim will not be targeted again, it does recognize that “all options” should be considered in these cases.

Preventing ransomware

The best protection against ransomware is prevention.

Learn, and teach your coworkers and employees, how best to protect yourselves, both personally and professionally, from hackers. Keep software up-to-date with the latest security upgrades.

In addition, ensure your data is backed up regularly. That way, if a ransomware attack happens, the victims can get professional help removing the malware from their systems, restore their data and move on.

Many companies have purchased insurance coverage to help pay the costs of recovering from ransomware – but some of those policies also include paying ransoms in the event of an attack.

Getting the data back isn’t a sure thing. Of the organizations that have paid the ransom, 20% haven’t actually recovered their data.

That presents victims with the certainty of spending some amount of money – whether it’s a ransom payment or a bill for a cybersecurity specialist – and not necessarily getting their data back.

An opportunity to engage

We have found another approach that could reduce the amount of money spent and simultaneously increase the certainty of data recovery.

Negotiating with hostage takers is tricky business, both online and offline. But many cybercriminals are often willing to bargain over the price of a ransomware payout. In fact, nearly three out of four ransomware hackers would return stolen data for a discounted price.

With cybercrime overall – of which ransomware is a large and growing component – slated to cost the global economy $6 trillion a year by 2021, the opportunity to lower costs could be very valuable. For people or organizations without insurance coverage, there is little to lose by trying.

When a ransomware attack begins, affected computers’ screens normally announce the attack, include a demand for payment, and show a countdown clock, after which, allegedly, the hijacked data will become irretrievable.

That time is a window of opportunity to negotiate with the attackers. Usually, ransomware attackers require their victims to buy bitcoin, a form of digital currency, in order to pay the ransom. Most people don’t know how to buy bitcoin in the first place, so often an attacker has to teach the victim what to do. This opens a channel of communication between the victim and the attacker, which is analogous to the starting point police experts use to defuse hostage situations.

Negotiating with cybercriminals

In general, the less the victim knows about how to purchase bitcoin, the more time the victim has to build up rapport and trust with the cybercriminal. During a negotiation, an attacker may extend payment deadlines, lower the ransom, decrypt some data as a show of “good faith” or provide step-by-step assistance in purchasing bitcoin.

These steps may be understood as offers to gain the hostage’s trust and may reveal the hacker’s willingness to be flexible. A victim can request some data be restored, in part to prove that the hacker actually controls the files.

If the attacker doesn’t provide any decrypted data, it may be a sign that the ransomware is one that just erases data, rather than holding it hostage. That type of attack cannot be reversed, even if a ransom is paid.

If that’s the case, then it may be smart to terminate negotiation and not consider paying the ransom, either.

A risky business

No strategy for dealing with a ransomware attack is without risk.

Paying the ransom appears to increase the chances of being targeted again in the future, according to one 2018 report. In a future attack, the attackers will be less likely to believe that you don’t know how to buy or send bitcoin.

Paying the ransom also lets the criminals, and at times rogue nations like North Korea who also mount ransomware attacks, earn significant amounts with minimal risk, possibly increasing the likelihood of others being targeted as well.

Declaring that you won’t pay the ransom has its own dangers, as Baltimore saw, paying millions in fees to recover data and rebuild systems. That data could, at least potentially, have been reclaimed for just thousands of dollars.

In a similar situation, the city of Atlanta was hit by “GoldenEye” ransomware, with cyberextortionists demanding $51,000 in bitcoin. Atlanta, like Baltimore, refused to pay. The city ended up spending more than $9.5 million in taxpayer dollars for recovery.

These events make clear the moral and ethical dilemma around fueling crime and efficiently using public resources, a quandary that can be lessened, if not relieved entirely, by negotiating.

More organizations are trying this new approach, seeking to lower ransom payments and recover data less expensively. For example, the municipal government of Mekinac, Quebec, Canada, managed to lower its ransomware payment by 55% through negotiations. In our view, it’s worth a try – and while certainly not risk-free, it could help.

[Deep knowledge, daily. Sign up for The Conversation’s newsletter.]

Scott Shackelford is a principal investigator on grants from the Hewlett Foundation, Indiana Economic Development Corporation, and the Microsoft Corporation supporting both the Ostrom Workshop Program on Cybersecurity and Internet Governance and the Indiana University Cybersecurity Clinic.

Megan Wade does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organization that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

Read These Next

Today’s obsession with authenticity isn’t new – being true to yourself has troubled philosophers for

Contemporary culture seems obsessed with authenticity – but the question of how to be ‘sincere’…

When Washington and the states are in conflict, the ultimate winner is not always certain

Conflict between Washington and the states is perennial and by design. Lack of clarity about who’s…

Trump offered a restrictive deal to universities that almost all rejected – but the Compact for Acad

The Trump administration is reportedly working on a revised version of the higher education proposal.