There’s no easy exit for the US in Afghanistan

The US is taking an untraditional approach in its peace talks with the Taliban. The new deal does not contain many of the elements that are typically key to a successful peace negotiation.

After 18 months of negotiations, the U.S. and the Taliban signed a peace deal on Feb. 29. It is expected that the deal will provide a plan for a comprehensive Afghan peace process.

The deal addresses the security of foreign troops; the Taliban’s commitments to sever ties with terrorist organizations; prisoner exchange; a gradual withdrawal of U.S. and foreign troops; and the beginnings of a negotiation between the Afghan government and the Taliban.

The Afghan government was not a party to the deal, and the Taliban must now negotiate a final peace agreement with that government. Yet that prospect is far from certain.

The U.S. approach of negotiating withdrawal first and initiate a peace process later is unheard of and has never been tested in the contemporary peace process. This nontraditional method is not necessarily doomed to fail, but it does not align with tactics of successful peace processes to date, as I know from my years of research on peace building.

An important deal

After 17 years of fighting, there was a growing consensus among the U.S. military leaders and administration that, if they wish to end the conflict in Afghanistan, they must negotiate an agreement, rather than continue to fight.

The Taliban-led violent events still taking place in Afghanistan illustrate that the Taliban are not slowing down.

The Taliban do not have a history of negotiating and maintaining peace.

The group’s willingness to now stop killing and engage in dialogue with the U.S. and the Afghan government is a good sign for all sides, including the U.S., that the end of the conflict may be near. This new deal is an opportunity for the Taliban to demonstrate their commitment to restrain from the use of violence.

The evidence on peacemaking

In my research, I have explored the content of peace agreements by looking at nearly 200 real peace accords. I wanted to understand: Why do some agreements result in lasting peace, while others fall apart?

While the steps of a successful peace process do not need to unfold in a particular order, my research and that of others shows that there are several clear steps that any process should take to maximize the chances of success.

The deal with the Taliban contains many elements that do not conform to patterns of successful peacemaking.

First, the deal does not address key ceasefire elements of successful peace deals, such as new recruitment in security forces, weapons transportation, or a mechanism to settle disputes from ceasefire violations.

Without these elements, it’s less likely that violence will diminish or that a ceasefire will hold. That, in turn, makes the peace process more difficult.

For example, in South Sudan’s 2017 ceasefire agreement, parties refrained from disseminating hostile propaganda and laid out rules for troop movement, new recruitment and training. They established a joint monitoring and verification body to settle ceasefire-related disputes.

Second, the U.S. and the Taliban deal does not provide a framework for how the negotiation with the Taliban will continue. Unlike Colombia’s Havana Process or the Philippines’ Bangsamoro peace process in Malaysia, there are no agreed-upon negotiation issues – like resettlement of refugees and displaced people, eradication of poppies or women’s rights – to guide the Afghan peace process. Often, finalizing such issues is a contentious and lengthy process in itself.

Without a framework like this, the proposed deal with the Taliban may or may not lead to any progress. For example, last year in Yemen, Houthi rebel fighters and Saudi-backed pro-government forces reached a ceasefire settlement but did not stop fighting. Evidence from other past ceasefires suggests that a formal ceasefire agreement alone is neither necessary nor sufficient to initiate a peace process.

Third, a ceasefire deal can be negotiated in any phase of the negotiation process.

In Nepal, after a broader political understanding was reached by political parties with the Maoists, a ceasefire with a code of conduct was negotiated before reaching a final agreement. In Colombia, a ceasefire deal was negotiated at the end of the Havana process.

It is easier to agree on ceasefire protocols when parties are making progress in negotiating other issues. The Taliban and the U.S. deal does not touch on political issues. The current Afghan government and the Taliban have different political visions – a recipe for a stalemate.

Even a failed peace process can help to improve future negotiation. For example, the Filipino government and the Moro Islamic Liberation Front negotiated several peace agreements between 1997 and 2010 that failed. They finally were able to negotiate a framework agreement in 2012, leading to a comprehensive agreement in 2014. (In the intervening years, some 3,200 people were killed.)

Turning failure into success in a peace process takes time. It is not clear what strategies the U.S. will take, should the Taliban fail to comply with the terms of the proposed deal. There is also a significant risk of stalemates in negotiations between the Taliban and the Afghan government.

Looking forward

Instead of identifying negotiating agendas, the deal focuses on the withdrawal of U.S. troops within 14 months.

The withdrawal of foreign forces has never been part of an agreement negotiated in the early phase of a peace process. After all, it means giving up political leverage.

A deal that sets a clear agenda for further negotiations holds more promise than a deal that focuses on the deadlines for the withdrawal of U.S. troops. Deadlines in peace processes are rarely met.

As the evidence from many peace deals shows, the only factor that matters for peace and stability is the implementation of the negotiated agreement, regardless of many missed deadlines. Therefore, the U.S. needs to show unparalleled commitment to support the peace process, if it wants to protect its security interests.

[Like what you’ve read? Want more? Sign up for The Conversation’s daily newsletter.]

Madhav Joshi is associated with a project that receives funding from the U.S. State Department for the work in Colombia. The funding has nothing to do with this article.

Read These Next

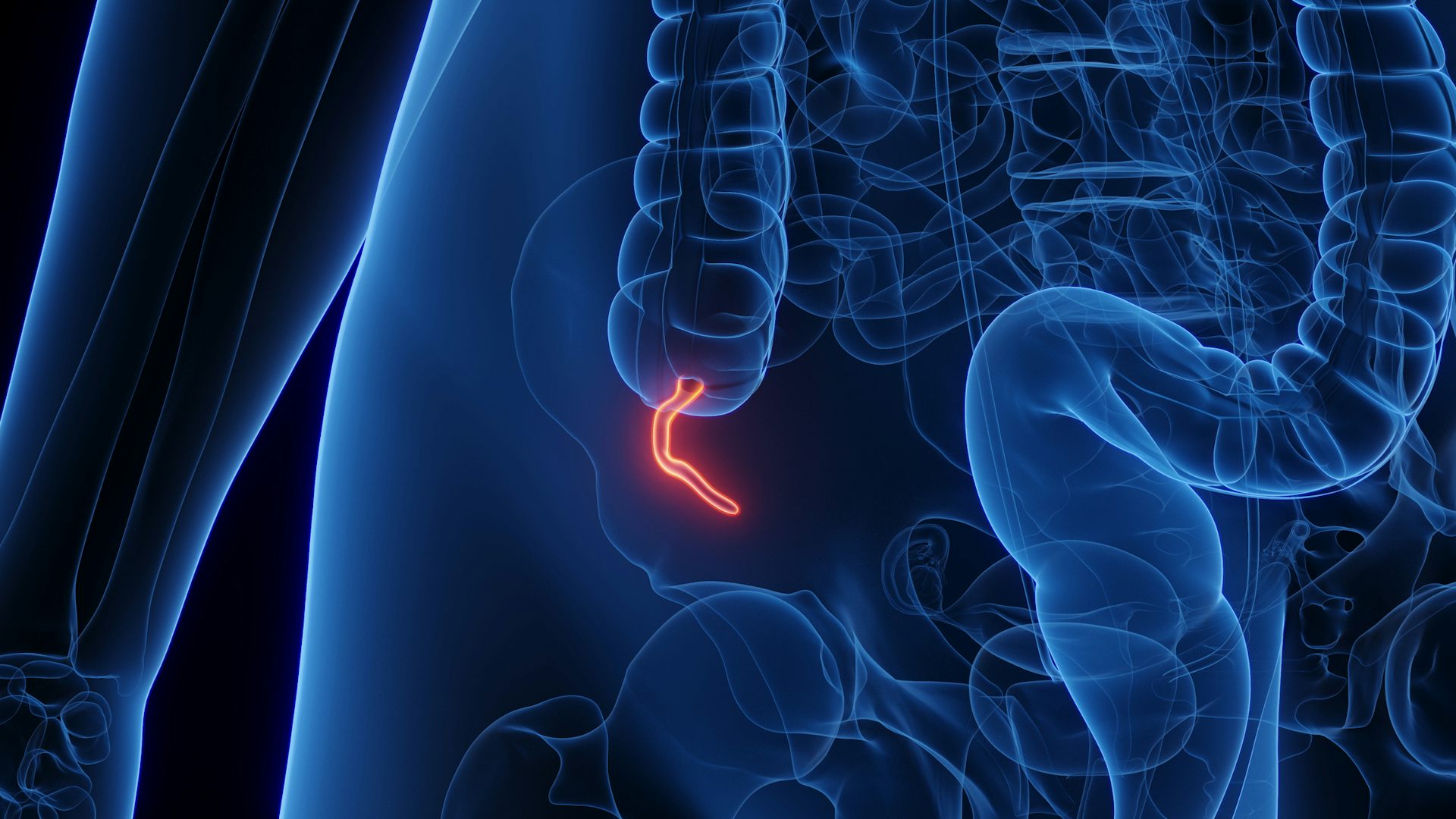

What does the appendix do? Biologists explain the complicated evolution of this inconvenient organ

The appendix has independently evolved at least 32 times across 361 mammalian species. What makes it…

Arming a Kurdish insurgency would be a risky endeavor – for both the US and Iran’s minority Kurds

Washington has long worked with Kurdish groups in the Middle East. But without sufficient support, encouraging…

China’s muted response over war in Iran reflects Beijing’s delicate calculus as a concerned onlooker

Beijing has denounced US-Israeli action in Iran, but has not rushed to come to the aid of its regional…