'Stolen' elections open wounds that may never heal

When the electoral process was helped along by practices that either were or appeared to be underhanded, the resulting wounds took a long time to heal – and may not ever have healed.

Allegations are flying left and right about potential – or actual – efforts to unfairly and secretly influence the outcome of the 2020 election. It’s a time when political scientists and constitutional scholars like to look back on other times when the electoral process was, you might say, helped along by practices that either were or appeared to be underhanded.

There are not many examples of so-called “stolen elections” in U.S. history, but the ones that had irregularities and were controversial, in 1824 and 2000, had an oversized impact on the decades that followed.

The ‘corrupt bargain’

Looking back to the first allegedly stolen election is a good reminder that U.S. elections used to be much more complicated than today. Yet there are still strong parallels.

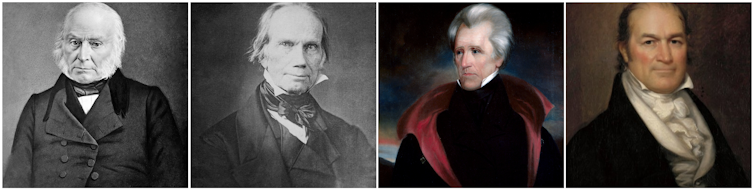

There were four candidates running for president in 1824: John Quincy Adams, Henry Clay, Andrew Jackson and William H. Crawford.

After the War of 1812, the United States entered a period historians now call “the Era of Good Feelings.” Among the public and politicians alike, there was a strong desire for national unity, and rare moment of declining partisanship.

To show his support for unity, President James Monroe, a Democratic-Republican who served from 1817 to 1825, asked Adams and Crawford to serve in his Cabinet, despite their rivalry within the Democratic-Republican Party. At the time, Clay, also a Democratic-Republican, was the speaker of the House of Representatives.

The fourth candidate was a comparative outsider. Jackson had made a name for himself as a military commander, both in the War of 1812 and afterward, fighting Native Americans in the southeastern U.S., before being elected as a Democratic-Republican senator from Tennessee in 1822. In his presidential campaign, he played up his Tennessee connections and styled himself as a man of the people and a political outsider. He claiming he would get rid of the “corrupt” aristocrats running the country.

The controversy began with the vote results. None of the four candidates got a majority of electoral or popular votes, though 41% of voters cast their ballots for Jackson, giving him the largest share of the votes and the clearest path to victory. Without an Electoral College win however, the decision came to the House of Representatives.

The 12th Amendment limited the House’s runoff decision to the top three candidates, eliminating Clay, who famously hated Jackson. Crawford had gotten even less of the popular vote, and had no way to win in the House.

There was, however, a directive put forth by the Kentucky legislature to Clay, their native son, to give all of their delegation’s votes to Jackson. Clay ignored this and persuaded the Kentucky delegates and many others in the House to vote for Adams. Jackson was shocked by the result and claimed that Clay had struck a bargain with Adams. Soon thereafter, Clay became the secretary of state for the Adams administration.

After the election, Jackson attacked Adams and the Washington insider for what he called their “corrupt bargain.” He and his allies left the Democratic-Republican Party and formed the party that is now the modern-day Democratic Party.

In 1828, Jackson ran as the Democratic candidate for president, and won, convincing a majority of voters that they needed someone like him to clean up the capital and help the common man. When he took office, he emphasized the capacity of the people to come to the right conclusions, shunning the idea that they needed to be controlled by elites. He wanted judges to stand for election and advocated for the abolition of the Electoral College.

Remember the hanging chad?

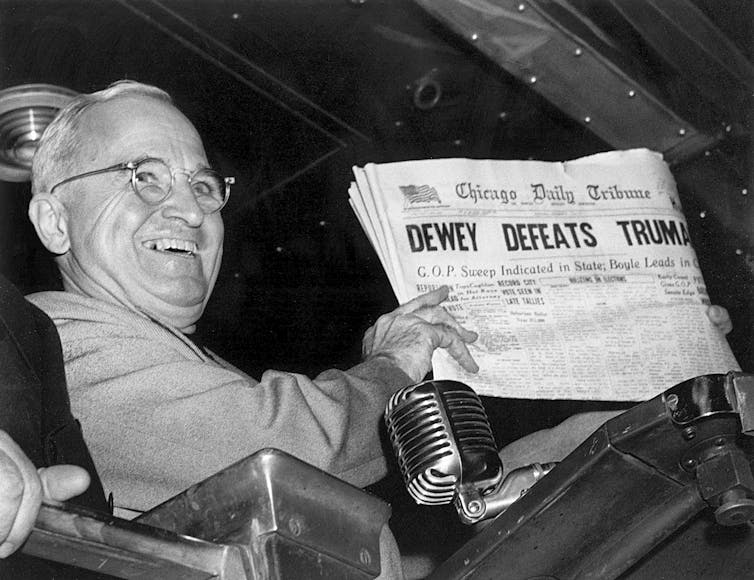

Much like Harry Truman’s surprise victory over Thomas Dewey in 1948, in the 2000 election Americans learned not to trust the polls. Many news organizations relied on exit polling to call Florida for Al Gore prior to the close of polling in several Republican-leaning districts.

Florida had 25 electoral college votes at the time. From all the other states, George W. Bush had 246 and Al Gore had 266, respectively. Florida, therefore, would be the state that decided the election, one way or the other. In a rare example of individual votes swaying the election, the decision about who would be the president of the United States came down to just 537 votes.

Lawyers from both parties soon flooded into the Sunshine State as the whole country waited for the results. Gore’s team wanted to force a recount, saying some counties’ ballots were hard for voters to understand, and had led some people, who thought they were voting for Gore, to accidentally vote for Pat Buchanan, a religiously conservative third-party candidate.

There were also problems with the physical structure of some ballots, which required voters to punch a hole to mark the candidate they supported. Some people did not punch a clean hole, leaving bits of paper hanging on – which became known as “hanging chads.”

These small-scale anomalies in a small number of counties in just one state were critical to determine who would be president. A legal back-and-forth about how to recount the ballots raced through state and federal courts, culminating in a Supreme Court ruling. The justices determined the Florida recount plan was not good enough and stopped the recount. Their decision effectively gave Bush the win in Florida, and therefore the Electoral College.

Critics noted that Bush had failed to win the popular vote, and that the Supreme Court vote was split 5-4, with the conservative justices in the majority delivering an outcome favorable to their political leanings.

What now?

In the 1824 election, historians see a country rebalancing itself politically and questioning what kinds of leaders the people wanted. In 2000, courts stepped into the most political of all processes: voting.

These elections’ outcomes divided the nation, in ways that were hard to heal, or perhaps never healed. When the winner lacks legitimacy and the loser can say the process was rigged, it is always bad for democracy. If there is, in one way or another, a “stolen” election in 2020 and the winner fails to bring the country together, it is unlikely the U.S. will see another Era of Good Feelings for a long time.

[Deep knowledge, daily. Sign up for The Conversation’s newsletter.]

Sarah Burns is affiliated with The Quincy Institute for Responsible Statesmanship.

Read These Next

Venezuela’s fragile forests face rising risks as US pushes for oil and critical minerals and illegal

The Orinoco Basin is one of the most biodiverse places on the planet. It’s also rich in oil, gold…

When Washington and the states are in conflict, the ultimate winner is not always certain

Conflict between Washington and the states is perennial and by design. Lack of clarity about who’s…

How does Iran go about selecting a new supreme leader? And who is in the running?

Media reports have cast the son of slain Ayatollah Ali Khamenei as a top candidate for supreme leader.…