The Senate has actually tied in an impeachment trial – twice

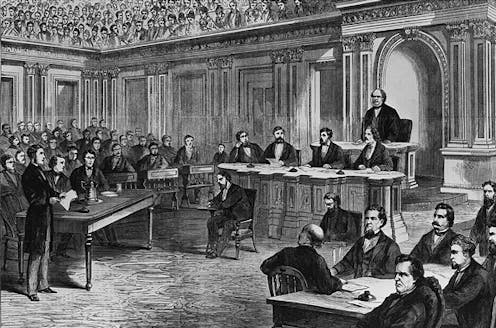

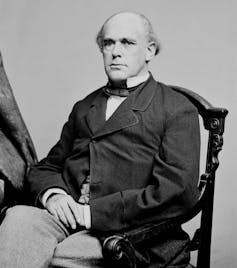

In 1868, during the impeachment trial of President Andrew Johnson, the Senate tied on two votes. Chief Justice Salmon P. Chase broke both ties.

The Senate will soon vote on whether to call witnesses in President Donald Trump’s impeachment trial. This vote could be 50-50.

If a tie occurs, Chief Justice John Roberts can cast a vote to break the tie, based on a careful reading of the Constitution and impeachment precedent. It has happened before.

The Founders’ words

I am a constitutional scholar and the author of a book on John A. Bingham, one of the impeachment managers in the trial of President Andrew Johnson. Let’s start by looking the constitutional text.

Article 1, Section 3 of the Constitution gives the vice president a tie-breaking vote if the Senate is equally divided.

However, the vice president doesn’t preside over a presidential impeachment because of his conflict of interest: He would become president if the trial resulted in a conviction.

Instead, the chief justice of the United States presides. In doing so, the natural inference is that he takes on all of the powers of the vice president. If he didn’t, presidential impeachment trials would be the only cases in which tie votes could not be broken. That’s an illogical result.

Some claim that the chief justice should be treated like an ordinary senator who presides over the Senate and cannot break ties. In my view, this comparison is deeply flawed. When a senator presides over the Senate (when the vice president is absent), that person does not get a tie-breaking vote because they already get one vote as a senator.

But neither the chief justice nor the vice president has a vote at all, unless there is a tie. The posture of the chief justice and the vice president toward the Senate is the same and, therefore, they logically must have the same power to break ties.

Two tie-breakers from a chief justice

The Senate rules on impeachment trials say nothing about what should occur in the event of a tie. But the Senate often relies on its precedents, rather than written rules, to govern its proceedings. So the lack of a rule specifying the chief justice’s tie-breaking power does not mean that he lacks that power.

During President Andrew Johnson’s impeachment trial in 1868, Chief Justice Salmon P. Chase broke two tie votes on procedural questions.

Some senators objected to the chief justice’s tie-breaking, so the Senate debated whether he could – and ultimately upheld Chase’s authority to break ties.

There were no tie votes during President Bill Clinton’s impeachment trial in 1999, so there is no other example to contradict the 1868 precedent.

Though the chief justice can break ties in the Senate, that says nothing about whether he must do so, nor how he should do so. These are questions that must be addressed separately depending on what the tie is about.

Gerard Magliocca does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organization that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

Read These Next

A successful USDA program that has supported more than 533,000 affordable rental homes in rural Amer

Hundreds of thousands of rural families could lose their affordable homes as mortgages the program supported…

Federal benefits cuts are looming – here’s how Colorado is trying to protect families with children

A combination of Colorado state tax credits for low-income families is predicted to lift more than 50,000…

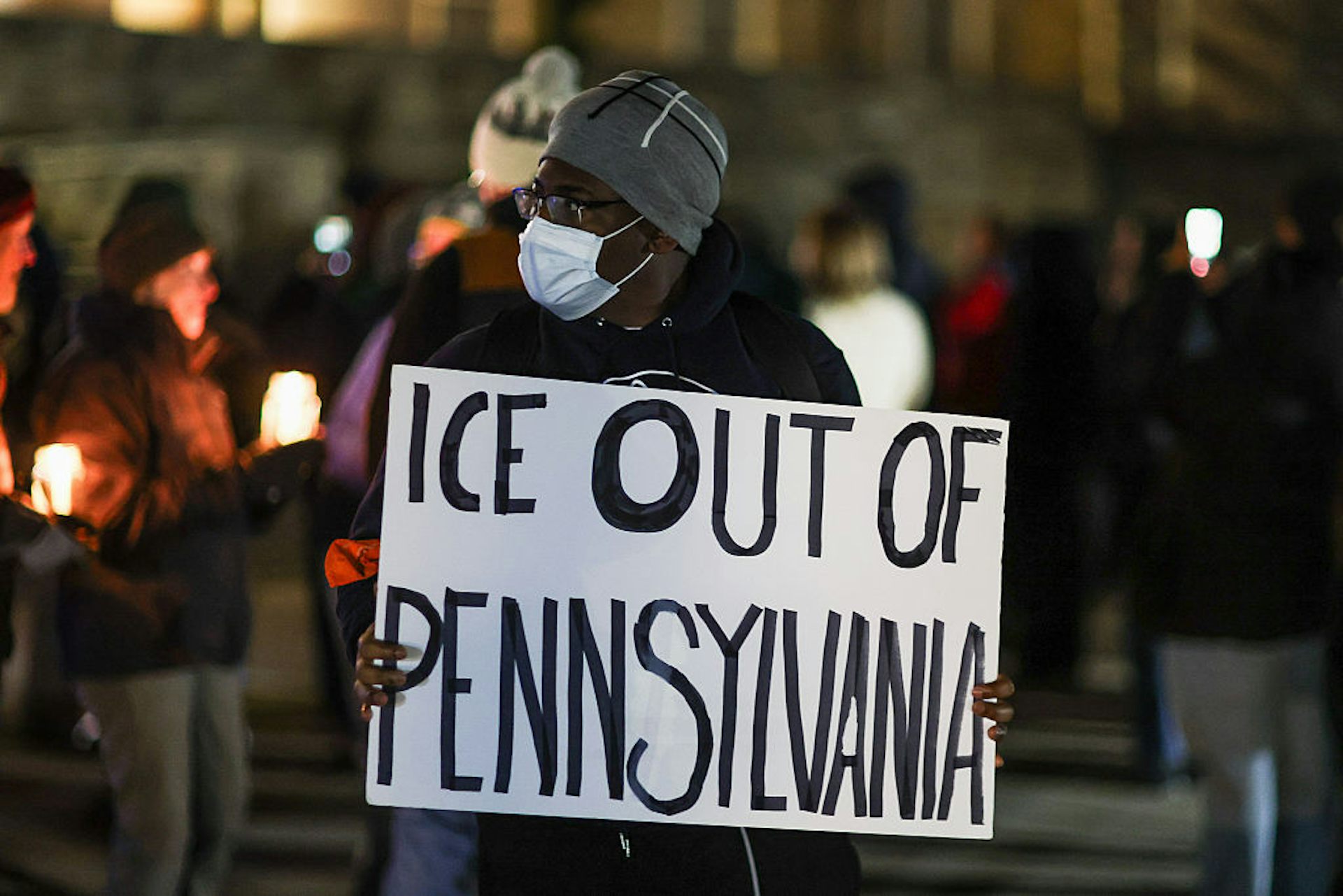

Legal refugees now face long detention after DHS reinterprets law on applying for a green card after

A new DHS policy could result in the detention of thousands of people who have lawful immigration status.