What US election officials could learn from Australia about boosting voter turnout

Many of the problems the US has with its election processes and outcomes are avoidable and don't happen in countries with different voting laws. Australia is a great example.

Not every country is plagued by rules that limit voters’ participation in elections, as is common in the United States.

In the past five years, restrictions on voting and voter registration purges have limited the number of Americans eligible to cast ballots.

In addition, the U.S. is the only major democracy that still allows politicians to draw their own district lines, an often-criticized conflict of interest in which public officials essentially pick their voters, rather than the voters picking their officials. That computer-aided gerrymandering of electoral districts reduces the number of districts with competitive races, contributing to low voter turnout.

Perhaps the fundamental problem, though, is that the system yields results the people don’t actually want. Twice in the last two decades, U.S. voters chose a president, George W. Bush and Donald Trump, who got fewer votes than his rival, Al Gore and Hillary Clinton.

All these problems are avoidable and don’t happen in countries that have different voting laws. Perhaps the best example is Australia, a country which is culturally, demographically and socioeconomically similar to the U.S. In my book “Rethinking U.S. Election Law,” written while I lived and studied their system Down Under, I outline many of the ways Australia has solved voting quandaries that persist in the U.S.

Mandatory voting, made easy

Australia’s most strikingly different law requires voting. All Australians must register to vote and actually cast a ballot. Not voting means a small fine (AU$20, or about US$14) will be imposed.

Australians don’t have to actually vote for a candidate: They can leave it blank, write in “none of the above” or even draw a picture – but they do have to turn in a ballot. As a result, Australia enjoys voter registration and turnout rates over 90%.

Voting is easier in Australia than in the U.S.. All voters can cast their ballots by mail, vote in person ahead of Election Day or show up to the polls on Election Day itself – which is always on a Saturday, when most people are off from work.

A different way of counting

Australia’s vote-counting rules are also different in important ways.

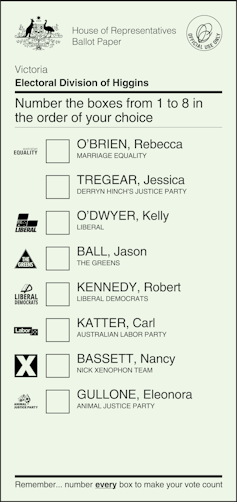

For its House elections, Australia uses what is called “preferential voting,” a form of ranked-choice voting.

Voters are allowed to rank their candidates in order of preference – 1st, 2nd, 3rd and so on. If a candidate’s first-choice votes add up to a majority of the overall ballots cast, that candidate wins, just like in any other system.

If no one wins a majority of the votes cast, the candidate with the fewest first-choice votes is eliminated and their supporters’ votes are redistributed according to these voters’ second choices. This process of eliminating candidates and redistributing those candidates’ supporters continues until one candidate has a majority.

This system eliminates what is at times called the “spoiler” problem in U.S. elections, where too many similar candidates split the majority’s vote, allowing a less-preferred candidate to win with a minority of the votes cast. For instance, in 2000, people could have voted for Ralph Nader while also showing that they would have preferred either of the other two candidates for president, Al Gore or George W. Bush.

Independent redistricting

Even with ranked-choice voting, any system where a single representative is elected for each district is vulnerable to gerrymandering. The lines can be drawn to give one party more seats than its mathematical vote share warrants.

To reduce that problem, Australia’s election districts are drawn by the Australian Electoral Commission, a politically independent commission of nonpartisan technical experts.

It’s well respected for being nonpartisan, with a good track record of keeping politics out of the redistricting process.

But even the Australian Electoral Commission isn’t perfect. As I detail in my book, like-minded people naturally cluster together in communities. That creates what some scholars have called “unintentional gerrymandering.” In the U.S., for example, Democratic voters overconcentrated in urban areas are unavoidably consolidated into districts with large Democratic supermajorities. That partially explains why, until recently, Republicans controlled the Virginia state legislature for years, even as Democrats won all the statewide and presidential elections.

Proportional representation

One way to fix the problem of gerrymandering – whether intentional or otherwise – is to move away from the concept of “winner-take-all” elections, in which 51% of the votes yields 100% of the power. In that system, significant minority voting blocs end up with no representation, leading to frustration and alienation.

For legislative elections, one potential solution could be proportional representation, in which a party earning 30% of the vote receives approximately 30% of the seats available. Rather than “winner take all,” this is “majority takes most, and minorities take their fair share.”

Proportional representation systems don’t have single-member districts, like having one congressperson per congressional district. Rather, representatives are elected either at-large or in multi-member districts. With districting eliminated, gerrymandering becomes impossible. Australia uses this system for its Senate, using a different form of ranked-choice voting called the single transferable vote.

Like the single-winner ranked-choice voting used in Australia’s House, if no candidate wins enough first-place votes to get a seat, weaker candidates are eliminated and their votes transferred to others based on second and third choices. But single transferable vote systems also reallocate what might be called “surplus” votes of winning candidates – extra votes beyond what candidates need to actually win – to ensure a more proportionate result.

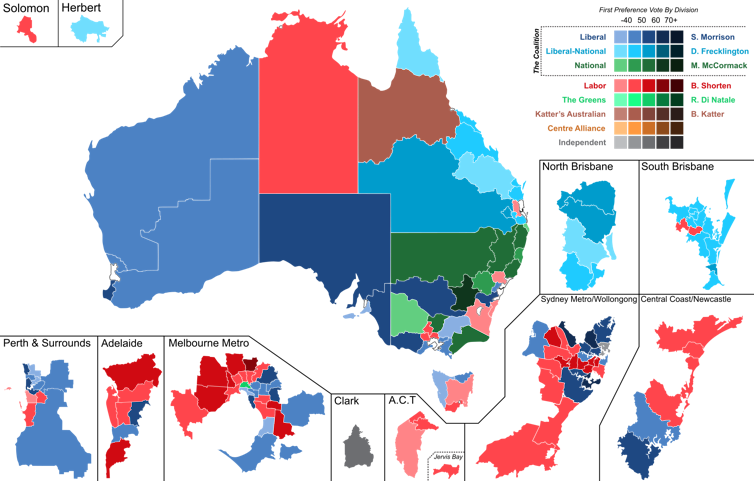

Proportional representation allows third parties to thrive, giving voters more choices. Australia offers a natural experiment between methods: For the last half-century, Australian voters nationwide have chosen single-member House representatives and used proportional representation to elect its Senate.

The result is that the Green Party consistently gets about 10% of the national vote, but zero seats in the House. However, in the Senate it gets about 10% of the seats, giving it a voice in the legislative debate. The difference is the move from winner-take-all in the House to proportional representation in the Senate. In addition, major parties vie to get second-choice support from Green Party backers, so the Greens’ concerns have real influence over national policies.

All these ideas – voting by mail, early voting, Saturday voting, ranked-choice voting, an independent redistricting commission and proportional representation – make Australia’s democracy more inclusive and representative than in the U.S.

[ You’re smart and curious about the world. So are The Conversation’s authors and editors. You can read us daily by subscribing to our newsletter. ]

Steven Mulroy does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organization that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

Read These Next

Massive US attacks on Iran unlikely to produce regime change in Tehran

President Trump has appealed to Iranians to topple their government, but a popular uprising is unlikely…

Iran will respond to US-Israeli strikes as existential threats to the regime – because they are

The latest attack on Iran goes far beyond previous operations by Israel and the US in both scale and…

Cuba’s speedboat shootout recalls long history of exile groups engaged in covert ops aimed at regime

From the 1960s onward, dissident Cubans in exile have sought to undermine the government in Havana −…