'Stop-and-frisk' can work, under careful supervision

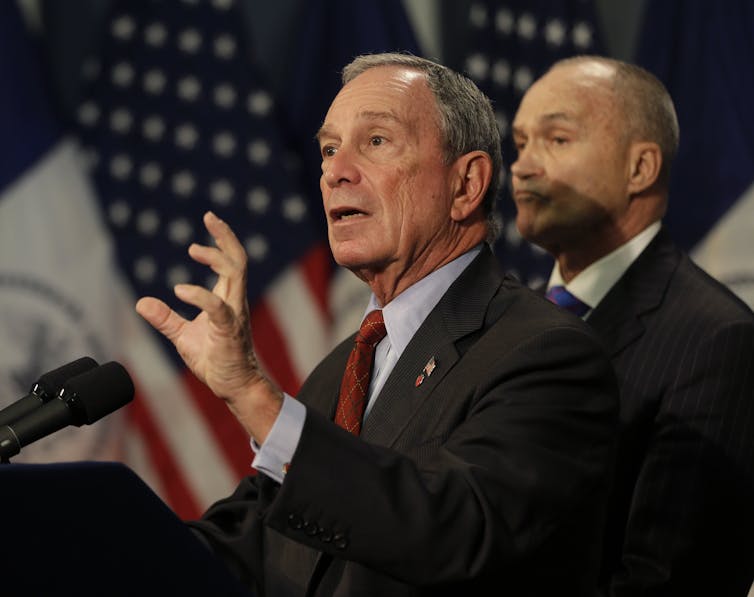

Former New York Mayor Michael Bloomberg apologized for his city's 'stop-and-frisk' police strategy. Two criminologists argue it isn't necessarily inherently racist – though New York's program was.

In mid-November, former New York City Mayor Michael Bloomberg apologized publicly for his backing of a practice intended to reduce violent crime that had for years been criticized as racially biased. “I realize back then I was wrong, and I’m sorry,” he said.

But his apology, made at a predominantly black church in Brooklyn, puzzled many observers. That included scholars of criminal justice like ourselves.

Bloomberg has long been a vocal supporter of a policy the city police department officially called “Stop, Question, and Frisk,” including during his time as New York’s mayor. In an effort to control crime, police aggressively and indiscriminately stopped and questioned people on the streets or in public housing projects. Police also often patted down suspects to check for weapons.

His apology was confusing because that phrase, often shortened to “stop and frisk,” is used to describe two different things.

As we wrote in our book, “Stop and Frisk: The Use and Abuse of a Controversial Policing Tactic,” one is a legitimate, constitutionally sanctioned tactic, grounded in a police officer’s reasonable suspicion that a particular person is engaged in criminal activity.

The other is an illegitimate, broad crime-control strategy that, more often than not, ignores the law’s requirement that a particular person be reasonably suspected of breaking the law.

A legal tactic

For centuries, the English common law tradition, which undergirds U.S. law, has recognized a police officer’s right to stop a member of the public to inquire about potentially criminal behavior. They can do this without needing to meet the legal standard for arresting the person and charging them with a crime – provided the officer had reasonable grounds to be suspicious in the first place.

In 1968, the U.S. Supreme Court codified that practice in its decision in Terry v. Ohio. In that case, a police officer saw two black men walking up and down a Cleveland street and repeatedly peering into a particular store’s windows. A white man joined them, after which the police officer approached the group, identified himself and patted down the men’s clothes – effectively, stopping and frisking them. The pat-down revealed that two of them were carrying illegally concealed firearms and burglars’ tools.

The men challenged the constitutionality of the initial stop and the subsequent pat-down.

When the case got to the Supreme Court, the justices established that stop-and-frisk was a practice fundamentally different than a search or seizure as specified by the Fourth Amendment. They concluded that the police officer had what they called a “reasonable suspicion” that the suspects were preparing to burglarize the store.

The court also ruled that police could pat down suspects to ensure they aren’t armed with weapons that could be used against the officers.

Taken together, the ruling gives police broad authority to decide when, whether and why to stop, question and frisk people.

In several rulings since 1968, the Supreme Court has expanded officers’ power to stop members of the public. That expanded power includes stopping someone in the open concourse area of an airport and requesting to see person’s ticket and identification, briefly searching a car for hidden weapons, stopping people for minor infractions while really investigating more serious crimes and even frisking people under the pretext of looking for weapons in hopes of finding drugs.

Left unchecked, all that discretion could lead to discriminatory, racially unjust and unconstitutional behavior in which blacks and Hispanics are targeted more often than their proportion of the population would suggest they should be.

A broad strategy

At its core, the stop-and-frisk approach is supposed to rely on more than a hunch. But the low burden of proof, the large discretion granted to police and the relatively invisible nature of these sorts of encounters combine to create real potential for abuse. Indeed, several U.S. police departments turned stop-and-frisk tactics into a wider, more aggressive strategy to cut down on crime.

Since 2002, New York City police officers, for instance, have stopped, questioned and often frisked hundreds of thousands of people each year. Police conducted more than 685,000 stops in 2011 alone. Over 82% of the people stopped were black or Hispanic, in a city where 52% of the population is black or Hispanic. Just 12% of all stops – of people of any race – resulted in an arrest or a summons.

Based on that data, a federal judge ruled in 2013 that the New York Police Department had unconstitutionally racially profiled its stop-and-frisk targets.

That year, New York police stopped 191,851 people; since 2014, under Bloomberg’s successor Mayor Bill DeBlasio, the number has dropped steadily. In 2018, just 11,008 people were stopped, and 31% of the stops resulted in an arrest or a summons.

Taking on crime

New York’s aggressive stopping-and-frisking practices happened at the same time as changes within the city’s police department, including a strategy in which police commanders identified what they called “high-crime areas” and flooded those locations with officers on foot patrols.

During that same time frame, the city’s crime rate dropped – especially its murder rate.

But crime rates stayed historically low even after officers dramatically reduced the frequency of stop-and-frisk encounters, signaling that other circumstances – not stop-and-frisk – drove the crime rate lower.

A path forward, with caution

Despite those problems in New York, we believe that it is possible for stop-and-frisk to succeed in contemporary policing – so long as it is not used broadly and indiscriminately.

Officers can be fair to suspects if they stop and question a person only when objective circumstances give rise to reasonable suspicion of criminal activity – and if they frisk that person only when clear facts suggest the person may be armed.

For instance, it could be appropriate for an officer to stop and frisk someone on the street for wearing a trench coat in hot weather. Another example that could warrant a stop-and-frisk would be if an officer sees someone repeatedly entering and leaving a bank or store without doing any business inside.

Those situations don’t depend on the race or ethnicity of the potential suspect. Racial or ethnic characteristics should be part of an officer’s decision to stop someone only if the person in other ways matches a description of a criminal suspect police are seeking.

Given the pervasiveness of racism and implicit bias, we believe that police departments that use stop-and-frisk tactics should be actively on guard against officers’ misuse of police power.

That includes careful recruitment and selection of new officers, excellent training and clearly written policies. Moreover, officers must be supervised in ways that increase accountability and transparency, potentially involving external oversight.

Body-worn cameras offer an opportunity for police departments to monitor and control officer decision-making during stop-and-frisk activities. Supervisors, training officers and even community members could systematically review body-worn camera footage as part of efforts to hold officers accountable for staying within the bounds of department policies and constitutional limitations.

If used properly, we believe, stop-and-frisk can be successfully and legitimately used while treating people with dignity and respect and giving suspects fair opportunities to tell their sides of the story. By making decisions fairly and acting with trustworthy motives, officers can ensure public safety while honoring citizens’ constitutional rights.

The authors do not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organisation that would benefit from this article, and have disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

Read These Next

Mobile clinics offer a practical way to improve health care access in maternity care deserts

Mobile health clinics are a practical but underused solution to the growing number of maternity care…

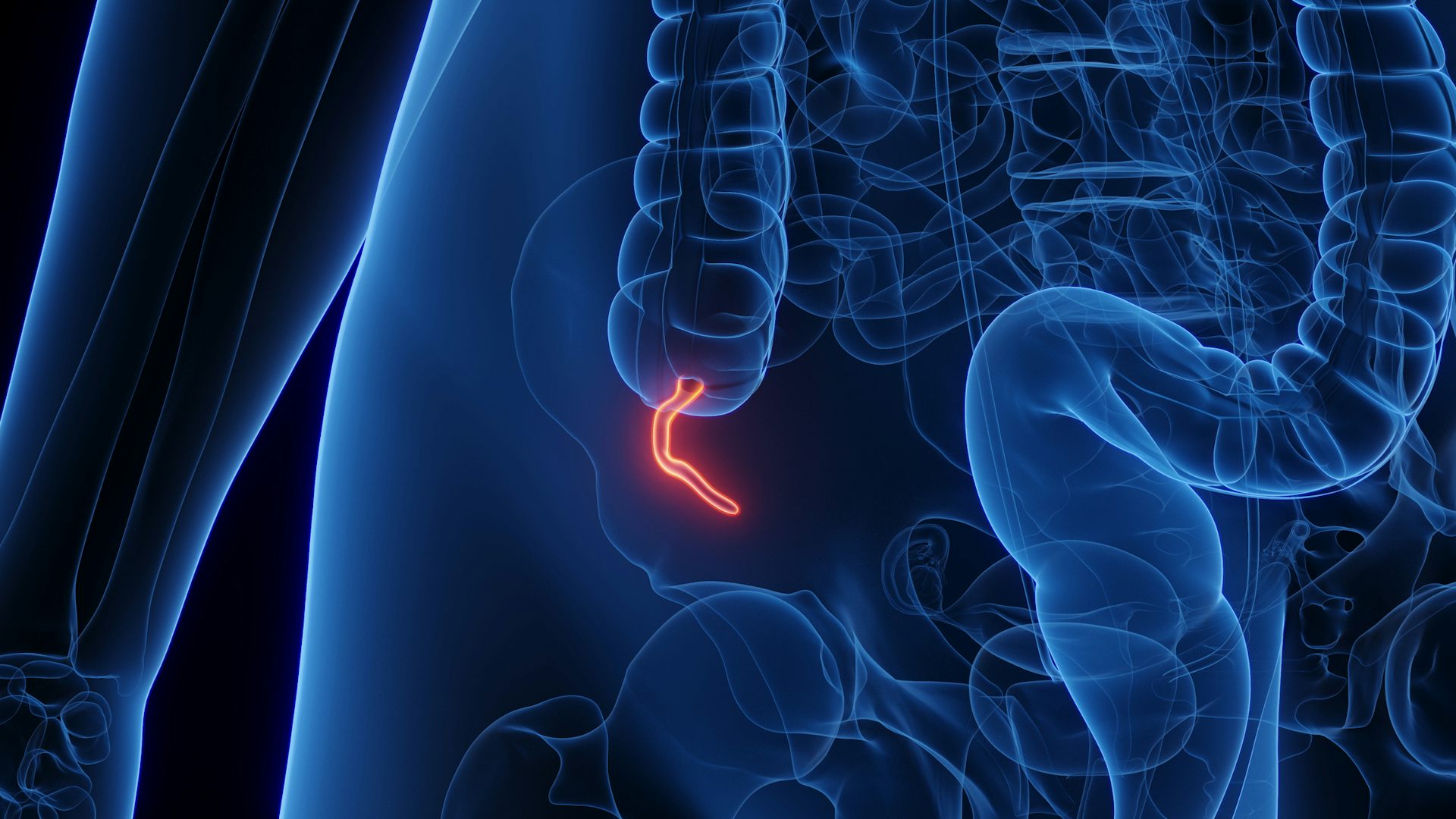

What does the appendix do? Biologists explain the complicated evolution of this inconvenient organ

The appendix has independently evolved at least 32 times across 361 mammalian species. What makes it…

I’ve studied MAGA rhetoric for a decade, and this is what I see in Hegseth’s boasts, action-movie on

Why does Defense Secretary Pete Hegseth brag and gloat in his statements about the Iran war? In the…