Hoda Muthana wants to come home from Syria – just like many loyalist women who fled to Canada during

Like today's Western women who joined ISIS and now want to return home, American women with British sympathies during the Revolution left the country – but many tried to bring their families back.

American emigrant Hoda Muthana begged American authorities last month to let her return to the United States.

Muthana, who was 19 when she left her family in Alabama in 2014 to join the proclaimed Islamic State caliphate, married three IS fighters after her arrival in Syria and was widowed twice.

Ultimately, Muthana claims, the birth of her son in May 2017 allowed her to see how foolish she had been.

Despite her insistence that she no longer harbors any radical sentiments, many Americans remain skeptical of Muthana’s intentions and believe she forfeited her American citizenship when she joined the enemy organization.

While the case has its own modern intricacies, early Americans confronted similar questions concerning the return of colonists who had supported Britain during American Revolution.

Much like Muthana’s insistence that she wants to return to America for the good of her young son, these exiled mothers also played a significant role leading their families back to their American homes after 1783 – despite resistance from their husbands.

Stay or leave?

During the American Revolution (1775-1783), roughly 1 in 5 white American colonists sided with the British. These colonists called themselves “Loyalists.”

When the war ended, the majority of these Loyalists stayed in the United States and reintegrated into American society.

Others chose to leave.

The formal conclusion of the war in 1783 began a series of evacuations from the last British strongholds of the eastern seaboard. In all, more than 60,000 people fled the American states during and after the war, with the majority of these refugees heading north to British Nova Scotia and the newly organized colony of New Brunswick.

Thomas Robie of Marblehead, Massachusetts, was one of the approximately 2,000 people who fled the state early in the conflict. A wealthy merchant, Robie resisted the colonial effort to boycott British-made goods in the late 1760s, angering the town’s patriot majority.

Fearing for his family’s safety as attacks against Loyalists turned increasingly violent, Robie left New England bound for Halifax, Nova Scotia, with his wife and four young children in late April 1775.

While Thomas’ business decisions had initially stirred up the locals’ anger, his wife made a more inflammatory denunciation of the town’s rebels.

“I hope that I shall live to return, find this wicked rebellion crushed, and see the streets of Marblehead so deep with rebel blood that a long boat might be rowed through them,” Mary Robie is recorded to have said.

According to Massachusetts lore, it was only her sex that saved her from physical harm.

Making home in exile

As a historian studying Loyalist refugees in Nova Scotia, I highlight how these colonists, and women in particular, navigated the physical and emotional hardships of exile.

All told, roughly 32,000 Loyalists arrived in Atlantic Canada, more than doubling the population and overwhelming the unprepared and poorly funded British colonial government.

In contrast to the fertile land the crown promised, the majority of refugees found Nova Scotia to be a barren and forbidding wilderness.

Of the widespread hunger, poverty and despair in Loyalist Halifax in June 1784, the oldest Robie child recorded in her diary, “If I look round me, what thousands I may see more wretched than myself.”

Rather than passively accept their fate, loyalist women took on important public roles in exile. From visiting new arrivals, to mourning at the funerals of total strangers, loyalist women’s empathetic actions built the intangible bonds of community that united a diverse group of refugees.

But few women ever warmed to their adoptive home.

The end of the war in 1783 forced thousands to move north, but it also offered earlier refugees, who had already tired of life in Nova Scotia, the opportunity to return to the United States. Loyalist wives and daughters became among the most outspoken proponents of repatriation.

Homesick for America

Although she had condemned the Revolution in 1775, Mary Robie quickly became a critic of life in Loyalist Halifax. She often complained about the dreary Nova Scotian weather and the monotony of her daily routine.

But after giving birth in March 1784 to her last child, a daughter named Hannah, Mary began to frame her desire to return in terms of her family’s future. She begged her husband “to give up on self” for sake of their children.

Thomas was unconvinced. In 1778, the Banishment Act of the State of Massachusetts named him among the Loyalists who had fled the United States “and joined the enemies thereof.” As an enemy of the state, and with his property confiscated in 1779, Thomas had little interest in returning.

The influx of refugees in 1783 had also brought a number of virulent diseases to Halifax; and when both mother and newborn daughter fell gravely ill, Thomas was forced to yield to his wife’s wishes. He reluctantly allowed his eldest daughter to accompany his wife and newborn back to Marblehead to find medical care.

Mary and her daughters arrived back in Marblehead in July 1784, where she became only more convinced that the family needed to come back for good.

“In short you must come here,” Robie wrote back to Thomas in Halifax, “for I shall never be content to live in the way I have done there.”

Even though she informed her husband that the people of Marblehead “would be glad to have you return and former animosities are all forgot,” Thomas remained unmoved.

Recovered from her illness, Mary had no choice but to bring her daughters back to Nova Scotia in October.

But Mary did not abandon her plan. For the next four years she continued to plead with her husband, eventually convincing him to let her and their eldest daughter return to Massachusetts again in 1788 to sell some of the hardware items he had trouble moving in Halifax.

During this trip, Mary encouraged a rival merchant in town, Joseph Sewall, to marry her daughter. With a concrete familial connection, Mary Robie had gained the upper hand.

“If you ever expect to see me again,” she wrote to Thomas in 1789, “you must come here.”

Thomas relented to his wife’s demands and landed in New England in July 1790. Although three of the Robie children had returned to Massachusetts, they left behind a son, Simon Bradstreet, who would go on to be one of the leading Loyalist politicians in Nova Scotia. Their daughter, Hetty, remained in Nova Scotia as well. Her husband, Jonathan Sterns met a more tragic end when a rival politician beat him to death in a street fight.

Although he had been proscribed from returning in 1778, facing a number of economic problems after independence, most New Englanders welcomed the return of merchants like Robie who had transatlantic connections.

Finding his former neighbors amiable, Thomas re-established himself as a merchant in the nearby town of Salem, while his wife traded visiting strangers with long walks in her garden.

“What fools we were to leave such a place,” she was fond of reminding her husband.

G. Patrick O'Brien received funding from The Massachusetts Historical Society and the University of South Carolina.

Read These Next

Welcome to the ‘gray zone’ − home to nefarious international acts that fall short of outright confli

Nations are becoming adept at provocations that fall in the area between routine peacetime actions and…

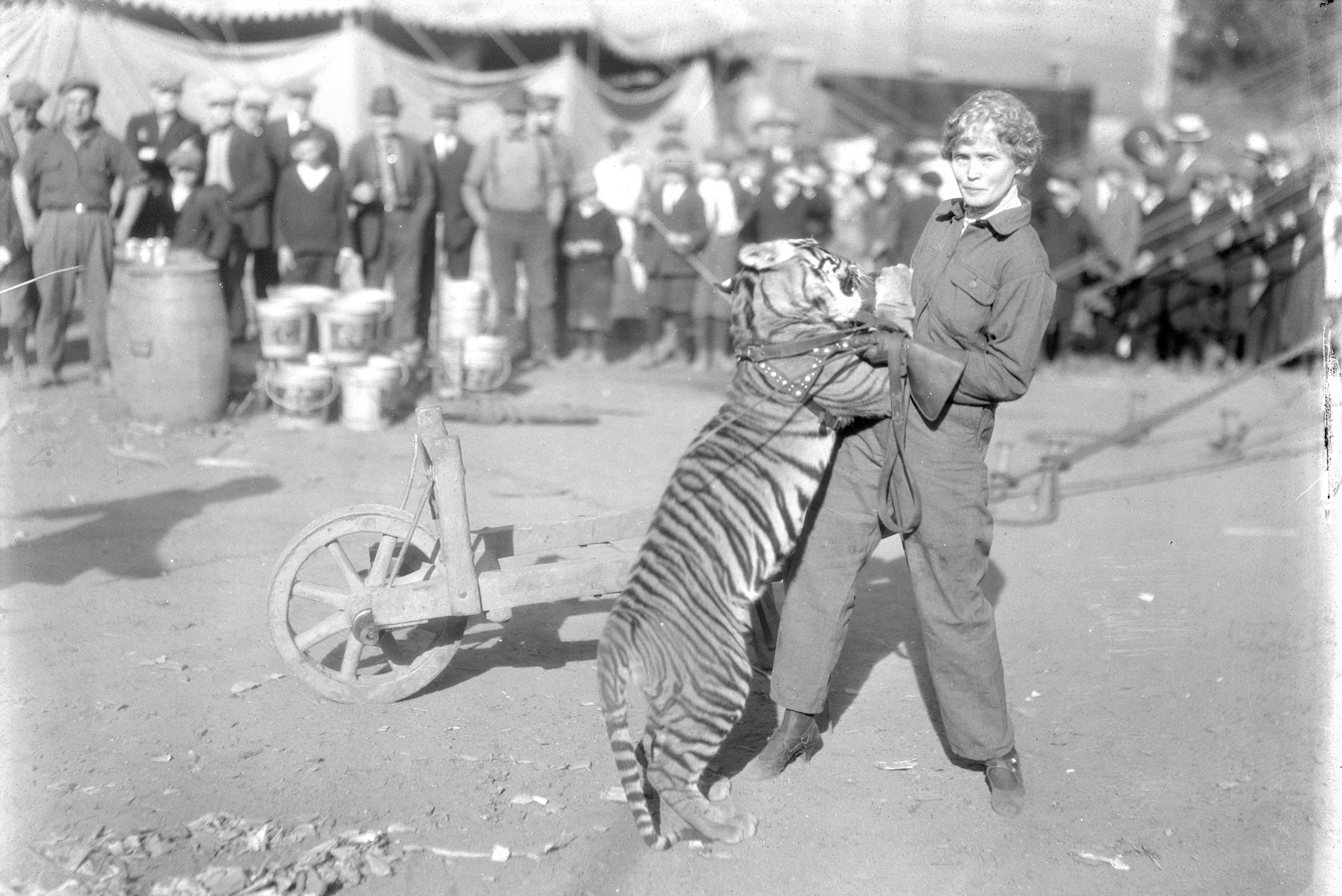

The inspiring and tragic story of Mabel Stark, America’s most famous female tiger trainer

Long before Joe Exotic became Tiger King, Mabel Stark reigned as Tiger Queen.

A Plan B for space? On the risks of concentrating national space power in private hands

What does it mean for national security if access to Earth’s orbit depends largely on one company?