A brief history of North Carolina's 9th District contested election – in 1898

This is not the first time the district has dealt with a contested election. Last time, there was no redo.

North Carolina is redoing an election to decide who will represent its 9th Congressional District, after an investigation uncovered evidence of election fraud during the 2018 midterms.

According to a recently completed investigation by the North Carolina Board of Elections, a political operative working on behalf of Republican candidate Mark Harris carried out a “coordinated, unlawful, and substantially resourced absentee ballot scheme” that may have provided Harris with hundreds of fraudulent votes.

The political operative paid friends and family members in cash to collect uncompleted absentee ballots, fill them out and then mail them in to the polls. During the investigation, Harris’ son testified that he had warned his father that the absentee ballot scheme was illegal.

Harris led by 905 votes on election day, but the Board of Elections never certified the result and soon began investigating. Speaking to supporters on Feb. 22, Dan McCready, the Democratic candidate, denounced the alleged fraud as perhaps “the biggest case of election fraud in living memory.”

My research on voter intimidation and election fraud in the late 19th-century United States focuses on contested congressional elections much like this one. One of the most interesting cases I have researched took place in that very same district, the North Carolina 9th, in 1898.

A century of redistricting has shifted the boundaries of the 9th District substantially. But comparing the fraud and intimidation then to the alleged fraud of 2018 provides critical context for understanding weaknesses in U.S. elections.

What to expect when you’re contesting

Contested elections happen when one candidate challenges the announced result as illegitimate.

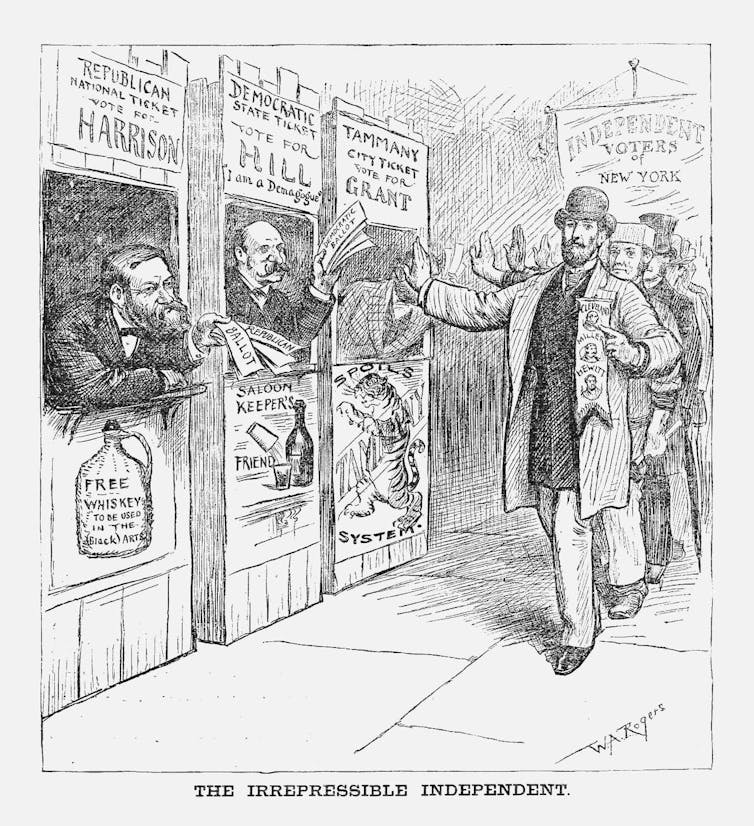

Such cases were far more common in the late 19th century as Republicans battled resurgent white supremacist Democrats for control of districts in the South. In the 1890s alone, there were 78 contested congressional election cases, more than half emerging from states that had seceded during the Civil War.

There were so many contested elections in this era in large part because voting happened in the open, without the protection of secrecy. When voters went to the polls in the 9th District in 1898, they picked up pre-printed ballots from party workers outside the polls and placed them in the ballot box – in full view of the community. Everyone could see who they voted for, including employers and party operatives who often sought to bribe or intimidate voters.

The lack of secrecy at the polls meant that the intimidators and bribers were also visible. Candidates who lost close elections were often able to present Congress with eyewitness evidence of the corrupt methods used against their voters.

Coercion at the polls became such a crisis that many states, under pressure from reform advocates, including the Knights of Labor, the nation’s largest labor union at the time, adopted secret ballots between 1888 and 1892.

Southern states lagged far behind in the trend towards ballot secrecy. North Carolina in particular failed to enact a secret ballot law until 1929.

The 1898 midterm congressional elections were contentious, and in North Carolina’s 9th District the campaign was vicious all the way to the end. Allies of the Democratic candidate, William Crawford, waged a campaign of racial terror. They gave inflammatory speeches, attacked Republican-leaning voters, stuffed ballot boxes, and lynched an African-American man the night before the election in an effort to terrorize African-Americans away from the polls.

When Crawford was declared the winner by just 218 votes, his Republican opponent, Richmond Pearson, accused Crawford of stealing the election through “bribery, intimidation, and irregularities” in the ballot counting process.

Pearson collected extensive witness testimony, which is documented in the papers of the House Committee on Elections, housed in the National Archives and more briefly in Chester Rowell’s historical and legal digest of election cases.

The experience of one African-American man named West Ray working as a wagon driver in the small town of Ivy, North Carolina, tells us a lot about what happened at the polls that day.

Ray’s polling place was located in the county store. As Ray entered the store to vote, the store owner, a man named W.R. Manney, pulled him aside and demanded he cast a Democratic ballot. When Ray refused, the store owner threatened to ban Ray from delivering goods for the store.

Ray understood, as he explained to a bystander who later testified about the encounter, that “if I vote Republican he won’t let me drive no longer.”

Still he pushed forward. Manney switched to bribery, offering Ray US$3 if he agreed to take a Democratic ticket. Again Ray refused.

Manney finally abandoned subtlety for violence, summoning over a group of white men who “bulldozed” Ray – pushing him away from the store to keep him from voting until the polls closed with the setting sun.

Ray’s story and other evidence that Pearson and his attorneys collected convinced the Republican-controlled U.S. House of Representatives that Crawford had no right to the 9th District seat. The House ejected Crawford and seated Pearson by a vote of 129 to 127.

Risks of convenience

Today, Harris’ campaign is accused of manipulating absentee ballots – exploiting a lack of ballot secrecy, much as his predecessors had done in 1898.

Absentee ballots solve a significant problem in modern U.S. elections by granting busy, disabled or physically remote voters easy access to the polls.

However, the mechanics of absentee voting offer potential avenues for fraud like that alleged in the 9th District. It is also possible that the lack of secrecy in absentee balloting may leave voters who fill out their ballots at home or at work vulnerable to intimidation. Thus far there is no documented proof of absentee ballot intimidation, but anonymous and anecdotal references in the past few years are troubling, if not conclusive.

The intimidation in 1898 and the alleged fraud in 2018 in the 9th District both offer extreme examples of what happens when access and convenience carry greater weight than secrecy and voter protection.

Absentee ballot fraud is extremely rare. Yet, more states are adopting policies that allow absentee voting without requiring citizens to provide a reason for not coming to the polls. Legislators should be careful to avoid recreating the errors of the past while solving the problems of the present.

The alleged fraud carried out by Harris’ campaign has received widespread attention and prompted calls for electoral reform. Federal laws including the weakened but still potent Voting Rights Act of 1965 provide far greater protection to voters today than voters in North Carolina in 1898 enjoyed.

Improving federal and state election laws to preserve voters’ privacy, access and representation during elections is a necessary goal. Yet, the painful history of fraud and intimidation in American elections, even just the history of this one congressional district, should remind us that protecting the right to cast a free ballot is a constant struggle.

Gideon Cohn-Postar has in the past received funding from the Gilder Lehrman Institute of American History, the Andrew Mellon Foundation, the Social Science Research Council, and the Dirksen Center. He is a member of the Democratic Party.

Read These Next

How Jesse Jackson set the stage for Bernie Sanders and today’s progressives

The coalitions that Jackson built during his presidential campaigns created enduring infrastructure…

How deregulation made electricity more expensive, not cheaper

Deregulation promised competition but delivered middlemen instead.

Florida’s immigrant entrepreneurs are creating jobs and prosperity in their communities

Stories of Florida’s immigrant entrepreneurs show how immigrants find opportunities and fill economic…