Why proposals to sell nuclear reactors to Saudi Arabia raise red flags

Exporting nuclear technology is lucrative, but without strict safeguards, buyers could divert it into bomb programs. Why is Saudi Arabia shopping for nuclear power, and should the US provide it?

According to a congressional report, a group that includes former senior U.S. government officials is lobbying to sell nuclear power plants to Saudi Arabia. As an expert focusing on the Middle East and the spread of nuclear weapons, I believe these efforts raise important legal, economic and strategic concerns.

It is understandable that the Trump administration might want to support the U.S. nuclear industry, which is shrinking at home. However, the congressional report raised concerns that the group seeking to make the sale may have have sought to carry it out without going through the process required under U.S. law. Doing so could give Saudi Arabia U.S. nuclear technology without appropriate guarantees that it would not be used for nuclear weapons in the future.

A competitive global market

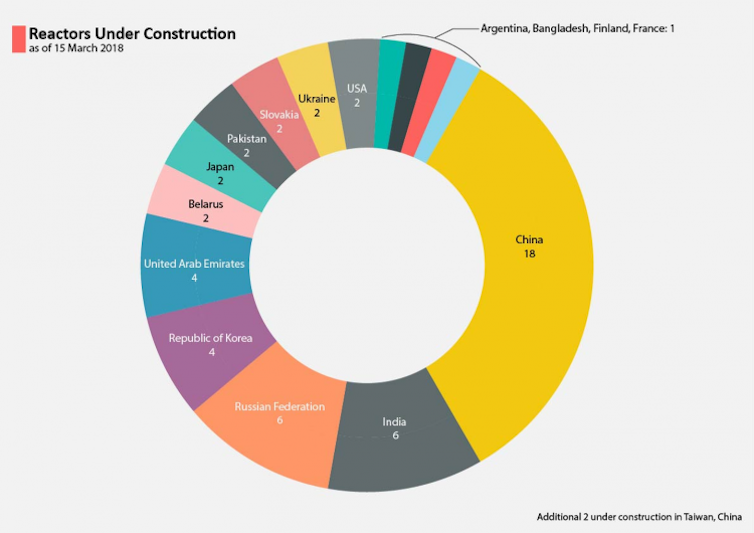

Exporting nuclear technology is lucrative, and many U.S. policymakers have long believed that it promotes U.S. foreign policy interests. However, the international market is shrinking, and competition between suppliers is stiff.

Private U.S. nuclear companies have trouble competing against state-supported international suppliers in Russia and China. These companies offer complete construction and operation packages with attractive financing options. Russia, for example, is willing to accept spent fuel from the reactor it supplies, relieving host countries of the need to manage nuclear waste. And China can offer lower construction costs.

Saudi Arabia declared in 2011 that it planned to spend over US$80 billion to construct 16 reactors, and U.S. companies want to provide them. Many U.S. officials see the decadeslong relationships involved in a nuclear sale as an opportunity to influence Riyadh’s nuclear future and preserve U.S. influence in the Saudi kingdom.

Why does Saudi Arabia want nuclear power?

With the world’s second-largest known petroleum reserves, abundant untapped supplies of natural gas and high potential for solar energy, why is Saudi Arabia shopping for nuclear power? Some of its motives are benign, but others are worrisome.

First, nuclear energy would allow the Saudis to increase their fossil fuel exports. About one-third of the kingdom’s daily oil production is consumed domestically at subsidized prices; substituting nuclear energy domestically would free up this petroleum for export at market prices.

Saudi Arabia is also the largest producer of desalinated water in the world. Ninety percent of its drinking water is desalinated, a process that burns approximately 15 percent of the 9.8 million barrels of oil it produces daily. Nuclear power could meet some of this demand.

Saudi leaders have also expressed clear interest in establishing parity with Iran’s nuclear program. In a March 2018 interview, Saudi Crown Prince Mohammed bin Salman warned, “Without a doubt, if Iran developed a nuclear bomb, we will follow suit as soon as possible.”

As a member in good standing of the Treaty on the Non-Proliferation of Nuclear Weapons, Saudi Arabia has pledged not to develop or acquire nuclear weapons, and is entitled to engage in peaceful nuclear trade. Such commerce could include acquiring technology to enrich uranium or separate plutonium from spent nuclear fuel. These systems can be used both to produce fuel for civilian nuclear reactors and to make key materials for nuclear weapons.

US nuclear trade regulations

Under the U.S. Atomic Energy Act, before American companies can compete to export nuclear reactors to Saudi Arabia, Washington and Riyadh must conclude a nuclear cooperation agreement, and the U.S. government must submit it to Congress. Unless Congress adopts a joint resolution within 90 days disapproving the agreement, it is approved. The United States currently has 23 nuclear cooperation agreements in force, including Middle Eastern countries such as Egypt (approved in 1981), Turkey (2008) and the United Arab Emirates (2009).

The Atomic Energy Act requires countries seeking to purchase U.S. nuclear technology to make legally binding commitments that they will not use those materials and equipment for nuclear weapons, and to place them under International Atomic Energy Agency safeguards. It also mandates that the United States must approve any uranium enrichment or plutonium separation activities involving U.S. technologies and materials, in order to prevent countries from diverting them to weapons use.

American nuclear suppliers claim that these strict conditions and time-consuming legal requirements put them at a competitive disadvantage. But those conditions exist to prevent countries from misusing U.S. technology for nuclear weapons. I find it alarming that according to the House report, White House officials may have attempted to bypass or sidestep these conditions – potentially enriching themselves in the process.

According to the congressional report, within days of President Trump’s inauguration, senior U.S. officials were promoting an initiative to transfer nuclear technology to Saudi Arabia, without either concluding a nuclear cooperation agreement and submitting it to Congress or involving key government agencies, such as the Department of Energy or the Nuclear Regulatory Commission. One key advocate for this so-called “Marshall Plan” for nuclear reactors in the Middle East was then-national security adviser Michael Flynn, who reportedly served as an adviser to a subsidiary of IP3, the firm that devised this plan, while he was advising Trump’s presidential campaign.

The promoters of the plan also reportedly proposed to sidestep U.S. sanctions against Russia by partnering with Russian companies – which impose less stringent restrictions on nuclear exports – to sell reactors to Saudi Arabia.

Flynn resigned soon afterward and now is cooperating with the investigation into Russian interference in the 2016 campaign. But IP3 access to the White House persists: According to press reports, President Trump met with representatives of U.S. industry, a meeting organized by IP3 to discuss nuclear exports to Saudi Arabia as recently as mid-February 2019.

Rules for a Saudi nuclear deal

Saudi leaders have scaled back their planned purchases and now only expect to build two reactors. If the Trump administration continues to pursue nuclear exports to Riyadh, I believe it should negotiate a nuclear cooperation agreement with the Kingdom as required by U.S. law, and also take extra steps to reduce nuclear proliferation risks.

This should include requiring the Saudis to adopt the International Atomic Energy Agency’s Additional Protocol, a safeguards agreement that give the agency additional tools to verify that all nuclear materials in the kingdom are being used peacefully. The agreement should also require Saudi Arabia to acquire nuclear fuel from foreign suppliers, and export the reactor spent fuel for storage abroad. These conditions would diminish justification for uranium enrichment or opportunities for plutonium reprocessing for weapons.

The United States has played a leadership role in preventing nuclear proliferation in the Middle East, one of the world’s most volatile regions. There is much more at stake here than profit, and legal tools exist to ensure that nuclear exports do not add fuel to the Middle East fire.

Chen Kane receives funding from the US Department of Energy's National Nuclear Security Administration.

Read These Next

Why Stephen Colbert is right about the ‘equal time’ rule, despite warnings from the FCC

The ‘equal time’ rule has been around for a century and aims to promote broadcasters’ editorial…

How Dracula became a red-hot lover

Count Dracula was originally a rank-breathed predator. His transformation into a tragic romantic mirrors…

Individual donors provide only a small slice of university research funding – but Jeffrey Epstein’s

A small portion of university research funding comes from individual donors. Most universities have…