One-party rule in 49 state legislatures reflects flaws in democratic process

The majority of US state legislatures are controlled by Republicans because legislative districts are drawn to favor them. Voters are catching on, but change will be slow.

Across the U.S., Republicans control 30 statehouses and the Democrats control 18. That is the largest number of one-party controlled state legislatures since 1914.

Minnesota is currently the only state where there’s not one party in control of the state legislature – Republicans have a majority in the state Senate chamber, while Democrats hold the state House chamber.

The Democrats’ so-called “blue wave” in the 2018 midterm elections was not big enough to put a major dent into the Republican’s control of state legislatures.

As a scholar of state politics, I believe partisan gerrymandering is a major reason why the Democratic wave fizzled as it reached the states. It is also why Democrats will likely have a difficult time regaining control in states as the redistricting process begins in 2020.

The power of partisan gerrymandering

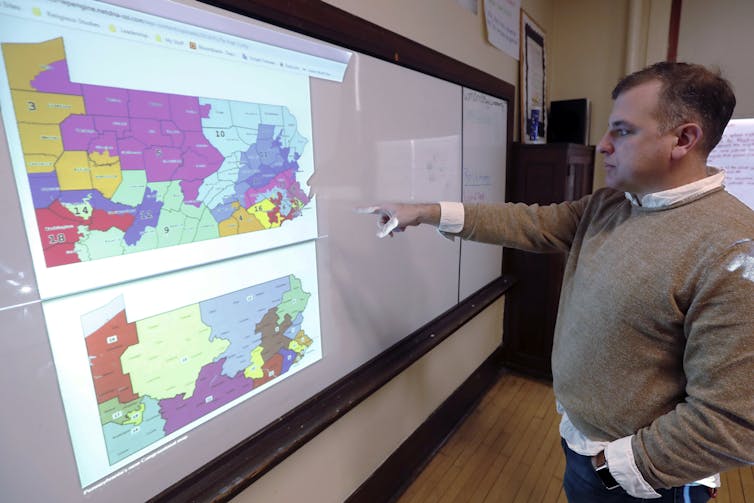

Partisan gerrymandering is the practice of drawing legislative districts that overwhelmingly favor one political party over another.

It creates safe seats for candidates of a particular party. Districts are created that contain mostly voters that support the majority party in the legislature, because in the redistricting process, the majority party gets to determine district boundaries. Recently, the Republican Party has simply been better at it.

In 2010, the Republican Party used redistricting to draw state legislative district lines that helped the party hold back the 2018 blue wave.

For example, in Pennsylvania, Michigan and North Carolina, a majority of people across each state voted for Democratic state House candidates. However, the Republican party still won a large majority of the legislative seats.

Why?

Because Democratic voters were spread out across many districts with very few districts having a majority of Democratic voters. Democratic candidates would need to win the votes of many Republicans to win the seat.

Policy impacts of partisan gerrymandering

This historic number of state legislatures controlled by one party will have important consequences for redistricting in 2020.

In 2020, the United States government will count its citizens as it does every 10 years through the census.

This also marks the beginning of the 2020 redistricting cycle. In 1962, the U.S. Supreme Court ruled in Baker v. Carr that congressional districts must be drawn to ensure that each citizen receives equal representation in Congress and in state legislatures. So congressional and state legislative district lines will be redrawn to reflect population changes documented by the census.

In most states, the state legislature is responsible for drawing the new congressional and state legislative district lines. This means that when one party controls both chambers, they are likely to draw lines that protect and increase their hold on the legislature. There is little the minority party can do to stop them.

One-party control of state legislatures affects more than just redistricting. It also makes it easier for the party in power to adopt more extreme public policies.

In Democratic controlled states like New York, these may include passage of laws that protect the rights of laborers, women, immigrants and LGBTQ people and increase restrictions on gun ownership. In Republican controlled states like Texas, laws might aim at protecting the rights of gun owners and the life of the unborn. Some of these policies may not match the preferences of the greater public in a state.

When partisan gerrymandering limits electoral competition, legislators worry less about re-election. Less worry about re-election can mean less need to appeal to the full range of constituents in their districts when passing laws.

For example, the influential conservative nonprofit the American Legislative Exchange Council, or ALEC, has successfully helped legislators introduce and pass legislation in many states that support a national conservative agenda. ALEC does this by writing the legislation and providing it to legislators.

Meanwhile, the State Innovation Exchange, a progressive nonprofit, provides research, training and policy expertise to state legislators interested in supporting a national progressive agenda. Their goal is to help state legislators introduce and pass progressive public policies.

Is change in the air?

As partisan gerrymandering has become more prevalent and extreme, citizens have become increasingly disenchanted and less supportive of the process.

In 2017, the League of Women Voters – a nonpartisan organization that encourages informed and active participation in government – sued the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania arguing that the state’s congressional map violated the state’s constitution. The Pennsylvania Supreme Court ruled that the districts favored Republicans in a way that undercut Pennsylvania’s voters’ ability to exercise their state constitutional right to vote in free and equal elections. In the ruling, the court stated that the congressional map “was designed to dilute the votes of those who in prior elections voted for the party not in power in order to give the party in power a lasting electoral advantage.”

As a result, the Pennsylvania Supreme Court invalidated the districts and drew a more competitive map itself. The new map led to the election of a congressional delegation that better reflects the party affiliation of Pennsylvania voters.

Currently, partisan gerrymandering litigation is pending in 12 states. A 2017 Brennan Center report analyzed the congressional district maps. They found consistent and high partisan bias in a number of states.

In 2018, voters in Michigan, Missouri, Colorado and Utah voted to make the redistricting process nonpartisan. They join Arizona, California, Idaho, Washington, Montana and Alaska in using independent redistricting commissions that are outside the influence of the legislature to draw legislative district lines. Most of these commissions have only existed since the late 1990s and early 2000s. The one exception is Washington, which adopted its independent redistricting commission in 1983.

A number of states, like Ohio, have also adopted reforms that give the minority party a larger voice in the process, but will still do little to stop the adoption of a partisan map. The hope is that the amount of bias will decrease.

Studies have shown that nonpartisan or bipartisan redistricting commissions lead to more competitive districts and potentially better representation for citizens. Pennsylvania, Michigan, Missouri, Colorado and Utah could be the start of a trend. The widespread adoption of nonpartisan or bipartisan commissions could lead to representation that is more responsive to citizen interests. Responsive governments are good for citizens.

Nancy Martorano Miller does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organisation that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

Read These Next

How the Emerald Isle shaped the Steel City – Pittsburgh’s rich Irish history

Long before Pittsburgh’s modern Irish celebrations existed, Irish immigrants helped shape the city…

I was teaching virtue and knowledge while lying on the side

While rationalizing deception is easy to do, developing the virtue of truthfulness is not.

As the Oscars approach, Hollywood grapples with AI’s growing influence on filmmaking

AI tools can now generate movie scenes, resurrect lost footage and replace entry-level jobs – forcing…